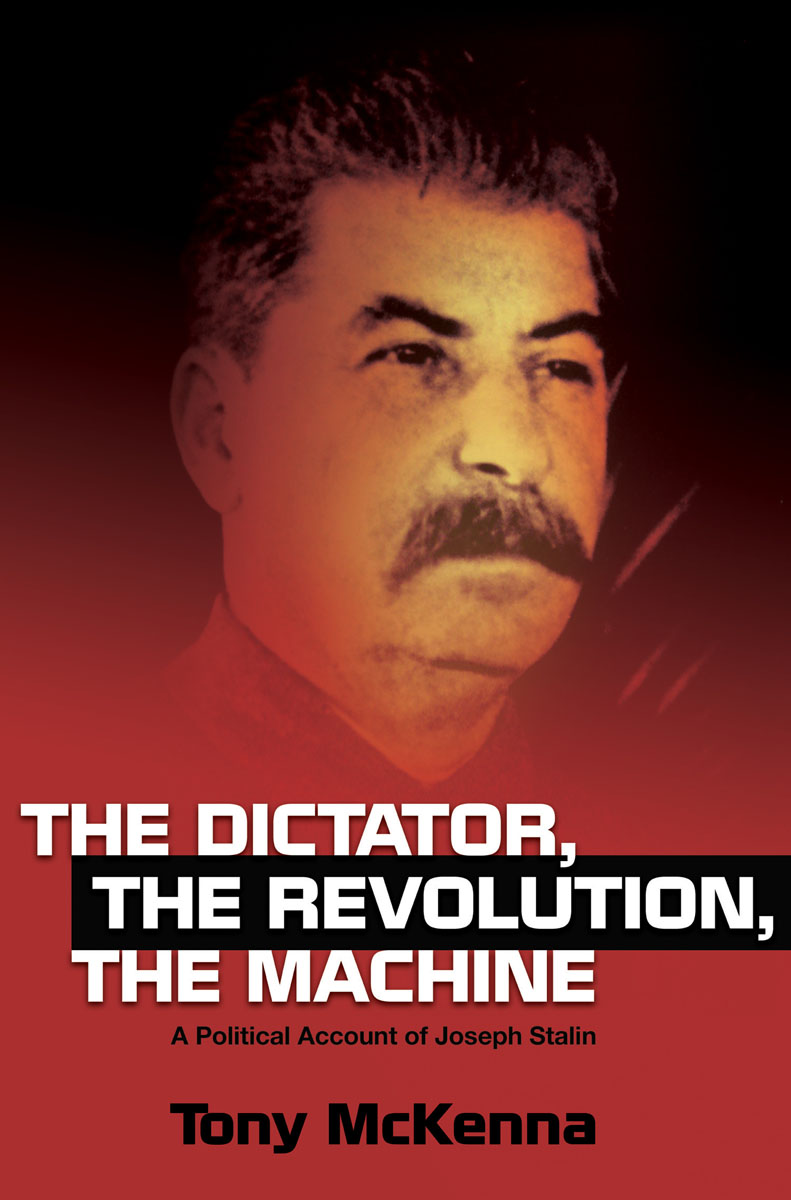

It is a commonplace wisdom that from the authoritarian roots of the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 grew the gulags and the police state of the Stalinist epoch. The Dictator, the Revolution, The Machine overturns that perspective once and for all by showing how October was inspired by a profound mass movement comprised of urban workers and rural poor a movement that went on to forge a state capable of channelling its political will in and through the most overwhelming form of grass-roots democracy history has ever known.

It was a single, precarious experiment whose life was tragically brief. In a context of civil war and foreign invasion the fledgling democracy was eradicated and the Bolshevik party was denuded of its social basis the working classes. While the party survived, its centrist elements came to the fore as the power of the bureaucracy asserted itself. From the ashes of human freedom there arose a zombified, sclerotic administration in which state functionaries took precedence over elected representatives. One man came to embody the inverted logic of this bureaucratic machine, its remorseless brutality and its parasitic drive for power. Joseph Stalin was its highest expression, accruing to himself state powers as he made his murderous, heady rise to dictator. This book examines his historical profile, its roots in Georgian medievalism, and shows why Stalin was destined to play the role he did. In broader strokes Tony McKenna raises the conflict between the revolutionary movement and the bureaucracy to the level of a literary tragedy played out on the stage of world history, showing how Stalinisms victory would pave the way for the Midnight of the Century.

Cover illustration courtesy of flickr.com;

https://www.flickr.com/photos/jbrazito/8401681543/;

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/

Tony McKenna is a writer whose work has been featured by The Huffington Post, ABC Australia, The United Nations, New Statesman, The Progressive, New Internationalist and New Humanist. His first book, Art, Literature and Culture from a Marxist Perspective, was published by Macmillan in 2015.

In this brilliant, moving and inspiring book, Tony McKenna provides a compelling analysis and portrayal of the historical causes of the Stalinist degeneration of the Russian Revolution, Stalins psychological development into a monstrous murderer of millions, and the gritty fearful realities of the lives his regime extinguished. The Dictator, The Revolution, The Machine also shows that the Russian experience doesnt seal the fate of humankind with respect to the prospects for the creation of a genuinely democratic socialist world. It concludes by affirming the desirability and feasibility of working-class self-emancipation and socialist participatory democracy. By fully confronting the horrors of Stalinist dictatorship while providing a sophisticated account of the historically unique combination of factors that give rise to and sustained it, Tony McKenna affirms the continuing vitality and relevance of revolutionary Marxism. Utterly compelling, a must read.

Brian S. Roper, Associate Professor in Politics at the University of Otago, author of The History of Democracy A Marxist Interpretation

Tony McKenna is a bona fide public intellectual who contributes to Marxist journals without having any connections to academia or to the disorganized left. This gives his writing a freshness both in terms of political insight and literary panache Although I think that McKenna would be capable of turning a Unix instruction manual into compelling prose, the dead tyrant has spurred him to reach a higher level his study is both an excellent introduction to Stalin and Stalinism as well as one that gives any veteran radical well-acquainted with Soviet history some food for thought on the quandaries facing the left today. Drawing upon fifty or so books, including a number that leftist veterans would likely not be familiar with such as leading Soviet military leader Gregory Zhukovs memoir, McKenna synthesizes it all into a highly readable and often dramatic whole with his own unique voice. It is a model of historiography and one that might be read for no other reason except learning how to write well. Louis Proyect, writer and activist, proprietor of The Unrepentant Marxist blog and moderator of Marxmail.org.

Copyright Tony McKenna 2016.

Published in the Sussex Academic e-Library, 2016.

SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

PO Box 139

Eastbourne BN24 9BP, UK

and simultaneously in the United States of America and Canada

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-78284-361-0 (e-pub)

ISBN 978-1-78284-362-7 (e-mobi)

ISBN 978-1-78284-363-4 (e-pdf)

This e-book text has been prepared for electronic viewing. Some features, including tables and figures, might not display as in the print version, due to electronic conversion limitations and/or copyright strictures.

Contents

Preface

This is a history book but it is unlike others. For a start it has no chapters. I wrote it, quite chaotically, over a short but intense period. It was first meant to be an essay of around 10,000 words. Somehow, though, it kept growing inevitably, organically as I saw the life of Joseph Stalin unfold in front of me; as I was pulled, with a sense of morbid fascination, into its terrible darkness. The writing developed this way, in the uneven and messy way of life itself. For that reason it has been impossible to compartmentalize the narrative into discrete and separate phases a chapter on Stalins engagement with Marxism here, a chapter on his foreign policy there. To forcibly cleave the text into a series of segments, each with a single theme, would have felt a little like dismembering the life I had struggled to bring into being through words. As though I were gutting the personality which I had placed in my literary sights of all its richness, its organic wholeness.

Not only is the book something of an oddity in terms of its structure but also, perhaps, by way of tone. History, especially as it is taught in universities these days, is supposed to be dispassionate, moderate, and denuded of emotion. This book is none of these. In academia objectivity and truth are often alleged to be anathema to the heat and passion of polemic. The student who succumbs to some form of partisanship, who is unable to relay events in a dry, dispassionate way, is usually dismissed as a naive idealist. A student who hasnt managed to check the fervour of his or her emotions and has not reached the stage of maturity whereby flash in the pan radicalism has been allowed to graduate into a more moderate and temperate world view. But what of such moderation? What of the idea that the true secret to political and historical objectivity is the ability to avoid extremes? To toe the middle line, to maintain a balance between more radical social polarizations and perspectives? How successfully does such a supposition encompass the reality of the world in which we live?

A recent study published by Oxfam showed that sixty-two people, sixty-two billionaires, own as much as the poorest half of the worlds population.many of whom languish in desperate poverty. The visceral contradiction between wealth and poverty is one which lies at the heart of our social organism. A contradiction between the billions of people who work in the factories and fields, the call centres and the cafes, the stations and the shops; the people who generate the wealth by which everyone lives and an ever concentrated minority who appropriate that wealth. Such a contradiction seems to me to be decidedly unbalanced. What does it mean to apply a balanced, moderate, middle ground analysis to a situation which is riven by the most extreme, volatile forms of social contradiction and which generates the most profound and abiding human suffering?

Next page