ALSO BY PETE AYRTON

NO MANS LAND

NO PASARN!

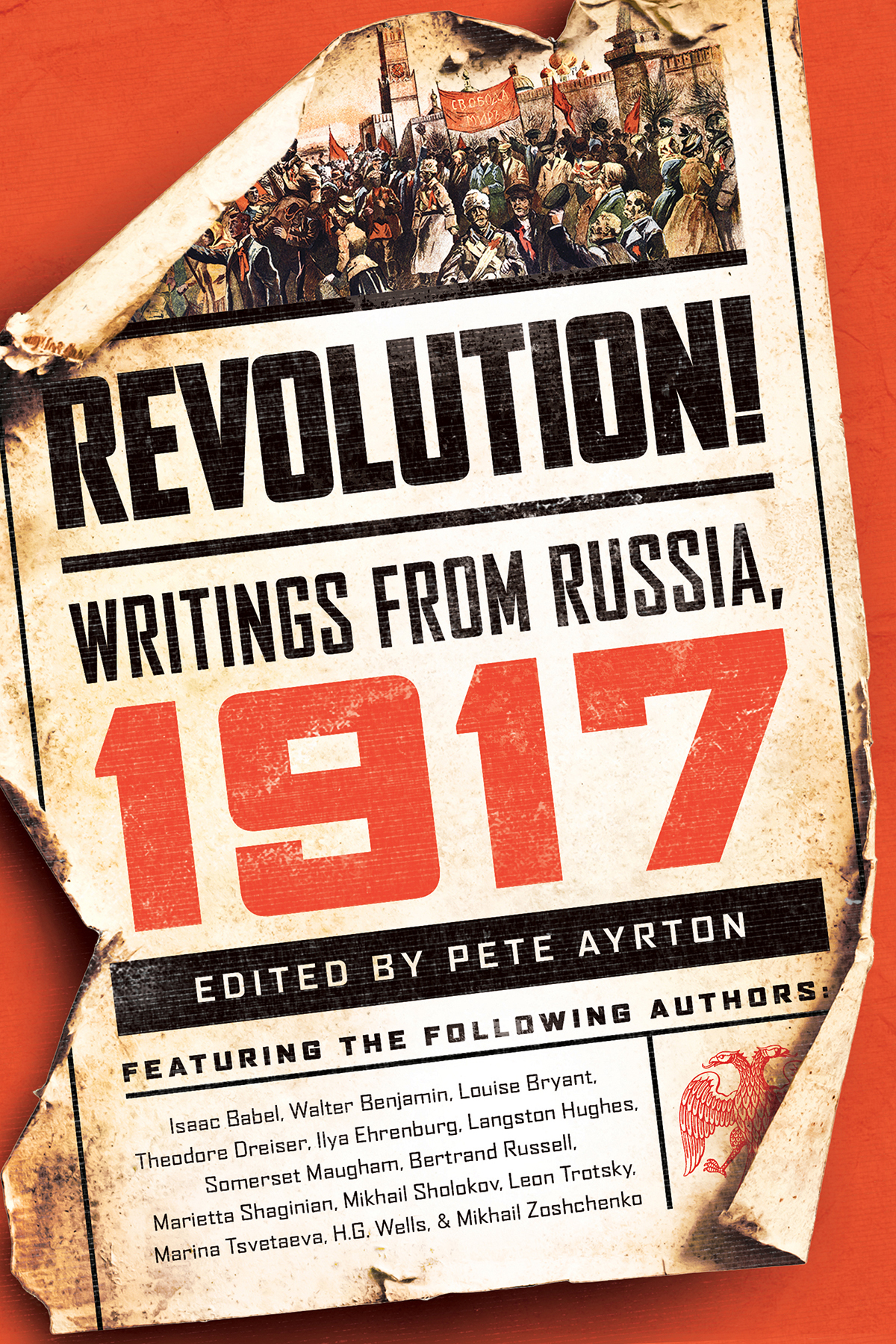

REVOLUTION!

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Selection, introduction, and editorial matter copyright 2017 by Pete Ayrton

Further copyright information is to be found on pages 362364

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition September 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in

part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who

may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine,

or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-520-3

ISBN: 978-1-68177-583-8 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

This book is dedicated to

JOHN BERGER

whose optimism was both

life-affirming and lucid.

Special thanks to Julian Evans, Robert Chandler, Boris Dralyuk and Lesley Chamberlain for sharing their knowledge of the literature of the period. To Stephen Smith, historian of the Russian Revolution, for generously giving me time and wisdom. To Jeremy Beale at Harbour Books and Claiborne Hancock at Pegasus Books for their publishing wisdom and support. To Edmund Fawcett, Sarah Martin, Malcolm Imrie and Ruthie Petrie who read and suggested improvements to the introduction. To Sarah, Carla and Oscar, for their enthusiasm and support that made compiling this anthology all the more worthwhile.

Soviet that the Provisional Government had been overthrown. In Russia we must now set about building a proletarian socialist state. At 10.40 p.m. the Second Congress of Soviets, which had been postponed since 20 October, finally opened against the sound of the distant artillery bombardment of the Winter Palace. At the news of the Storming of the Winter Palace the non-Bolshevik parties walked out of the Congress of Soviets. A Bolshevik government with Lenin as chairman was established, with its first priority being to end the war. Armistice negotiations began in Brest-Litovsk in November and the Treaty with Germany was signed in March 1918; extremely punitive, it took away from Russia territory that included a third of the population, over half of its industrial production and nine-tenths of its coal mines. Defeated in turn by the Western Allies, Germany signed an Armistice in November 1918 and abandoned the gains made in Eastern Europe and Russia. In the ensuing fight over these now contested territories, White Russian armies led by Yudenich and Denikin attacked Soviet forces. In October 1919, the White armies almost took Petrograd. However, by the next year the Red Army led by Trotsky was victorious and the Civil War was coming to an end.

These momentous events provide the background to the contributions in Revolution! In showing that liberation was possible, they brought great hope and exhilaration to people the world over. The autocratic Tsar had been replaced by a government speaking for the people, a government committed to ending the war, to expropriating factories and land and to introducing a new era of human dignity. Over the next ten years, many of those hopes were to be disappointed. But it is impossible to overestimate the expectations vested in the Soviet government that came to power in October 1917 expectations that inspired revolutionary movements all over the world during the twentieth century.

The extracts included in Revolution! Writings from Russia, 1917 come from three different sources:

1. Foreign writers and intellectuals who visited the Soviet Union after the Revolution and wrote about their experiences: sympathetic to the Revolution, they came from all over the world. They included Arthur Ransome and H. G. Wells from Britain, John Reed, Louise Bryant and Langston Hughes from the USA, Victor Serge from France, Walter Benjamin from Germany, Claude McKay from Jamaica, Panat Istrati from Romania.

2. Russian writers who stayed in the Soviet Union and wrote under conditions of increasing censorship. In the first decade after the Revolution, the Bolshevik government allowed different interpretations of what art and literature should be to coexist. So there was room for Isaac Babel, Mikhail Zoshchenko, Alexandra Kollontai, Ilf and Petrov and Lev Lunts. By the end of the 1920s, Stalin had strengthened his grip on power and socialist realism became the only permissible literature.

3. Russian migr writers who, after the Revolution, did not feel in sympathy with developments in the Soviet Union and emigrated before 1925 while it was still possible to leave. Teffi, Edith Sollohub and Nina Berberova were among the many who followed this path.

Foreign Writers and Intellectuals

The expectations raised by October 1917 were on a truly epic scale. As the international ruling classes feared, the Russian Revolution showed working-class and peasant movements all over the world that rapid change was possible. While the most acute revolutionary uprisings were in Europe in countries with a developed working class like Germany and Italy, there were also revolutionary upheavals in Egypt, Mexico and India, among others. The Bolshevik government in Russia had quickly fulfilled its commitment to end Russian involvement in the war. It had confiscated land and factories from the owners and embarked on a series of progressive social measures. Not surprisingly, this enthusiasm brought to the Soviet Union in the years following October 1917 many progressive sympathisers who wanted to see for themselves how the promised land was faring: many of the pieces in Revolution! capture what they saw. There were those, such as Beatrice and Sidney Webb, whose faith in Communism and the Soviet Union never wavered. However, the majority of contributors featured here found at some point or other that the discrepancies between what they had been led to believe was happening and what was actually happening were too great; their early enthusiasm was curbed or revised. For most, the moment of reckoning was postponed by the Civil War: they accepted that in a war it was legitimate for a government to curtail freedoms such as freedom of the press, of political opposition and of the right to strike. When the dangers of the Civil War receded and the Bolshevik government showed no signs of reintroducing the suspended freedoms, many early sympathisers were forced to take stock.

For Victor Serge, it was the Kronstadt Uprising that was decisive. In March 1921, the sailors of Kronstadt had mutinied in support of the striking workers of Petrograd. Their demands were for a renewal of the programme of the 1917 Revolution: elections to the Soviet by secret ballot, freedom of the press for all revolutionary parties and groups, the release of revolutionary political prisoners. The Bolsheviks refused to negotiate and after ten days of heavy fighting the uprising was defeated with bloody force and Kronstadt taken back. Serge writes about the period immediately after Kronstadt:

The truth was that emergent totalitarianism had already gone halfway to crushing us. Totalitarianism did not yet exist as a word; as an actuality it began to press hard on us, even without our being aware of it...

Next page