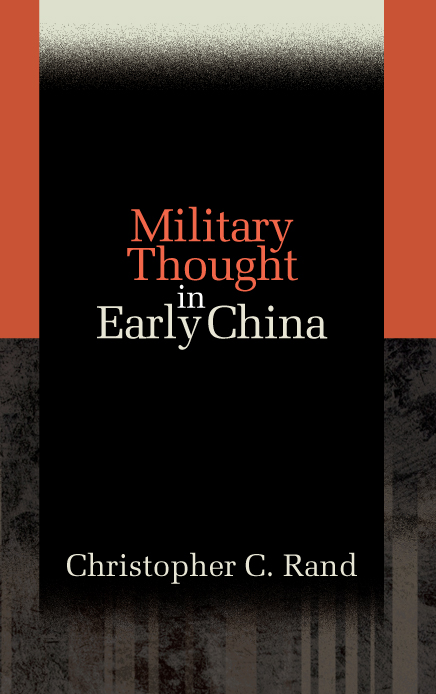

Christopher C Rand - Military Thought in Early China

Here you can read online Christopher C Rand - Military Thought in Early China full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: State University of New York Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Military Thought in Early China

- Author:

- Publisher:State University of New York Press

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Military Thought in Early China: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Military Thought in Early China" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Military Thought in Early China — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Military Thought in Early China" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Military Thought

in Early China

Military Thought

in Early China

Christopher C. Rand

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2017 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Eileen Nizer

Marketing, Anne M. Valentine

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rand, Christopher C. (Christopher Clark), 1950 author.

Title: Military thought in early China / by Christopher C. Rand.

Description: Albany, NY : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016031409 (print) | LCCN 2016044927 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438465173 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438465180 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Military art and scienceChinaHistory. | ChinaIntellectual lifeHistory. | MilitarismChinaHistory.

Classification: LCC U43.C6 R44 2017 (print) | LCC U43.C6 (ebook) | DDC 355.001dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016031409

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The writing of this brief history of military thought in early China began more than forty years ago as the topic of my doctoral dissertation in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at Harvard University. At that time, in the mid-1970s, the Cultural Revolution in the Peoples Republic of China was drawing to a close and archeological excavations throughout China were just beginning to reveal entirely new facets of cultural life in the early Sinitic realm. It was an exciting time to be studying early Chinese intellectual history (as it continues to be today), and I was eager to examine how these new findings, particularly regarding military affairs, fit with our previous knowledge of how early Chinese philosophers thought about their world and society.

Under the guidance of Professors Benjamin I. Schwartz, Yu Ying-shih, Yang Lien-sheng, and others at Harvard, I succeeded in completing my PhD thesis in May 1977 on the role of military thought in early Chinese intellectual history. I began writing journal articles based on my thesis and looked forward to obtaining a suitable position in academia where I could teach Chinese history and literature, as I had already done as a teaching fellow for Professors John K. Fairbank and James R. Hightower, and continue my research into Chinese intellectual developments. However, destiny changed that hoped-for trajectory. Rather than obtaining an academic position, I became an employee of the United States government, where I continued to work on Chinese affairs for most of the next thirty years.

After retirement, I decided to resume my study of China in the role of an independent scholar. One of my projects has been to reassess my dissertation of long ago to see whether my conclusions were still valid in the wake of continuing archeological revelations in the intervening years and new examinations by other researchers of the development of military thought in China. There have undoubtedly been many excellent achievements in this field in the decades since I left Harvard, including publications by those who were my fellow graduate students in the 1970s, such as Professor Robin D.S. Yates at McGill University and Professor Victor H. Mair at the University of Pennsylvania. Nevertheless, I felt that the approach and conclusions of my forty-year-old study, if thoroughly updated and succinctly recast, might still make a small contribution to a general understanding of this unique strain of Chinese philosophical inquiry. For that reason I proceeded with a total revamping of my earlier work, sharpening my arguments and adding new evidence in order to make a more complete history of the ideas underpinning military strategy in early China.

I can only hope that the reader will find my efforts worthwhile.

For a long time, both inside and outside China, relatively little scholarly attention was given to military thought in early China beyond consideration of the best known of Chinese military treatises, Sunzis Military Methods (Sunzi bingfa ). This was chiefly because of the Chinese traditional bias in the imperial era against the value of military affairs in comparison to civil affairs, as well as a limited number of extant primary source materials on warfare from the early period of Chinas history. Scholars have long been aware from the fifty-three titles compiled by Liu Xiang (798 BCE) and his son, Liu Xin (ca. 50 BCE23 CE), and placed by Ban Gu (3292 CE) in the military book section (Bingshu le ) of the Treatise on Literature (Yiwen zhi ) of the Hanshu that there was a wealth of works devoted to martial affairs in the Han and earlier periods of Chinese history. However, most of these works were presumed permanently lost.

Since the 1970s, however, several previously unavailable documents devoted to military strategy and tactics or related loresome perhaps versions of works listed in the Hanshu Treatise on Literaturehave been unearthed from widely dispersed archeological sites dating to the Western Han dynasty (202 BCE8 CE) and earlier. The most prominent of these are works addressing military lore and theory that were found in Western Han tombs in Yinqueshan , Shandong Province, in 19721973; Mawangdui , Hunan Province, in 19721974; Dingxian , Hebei Province, in 1973; Shangsunjiazhai , Qinghai Province, in 1978; and Zhangjiashan , Hubei Province, in 1983. In addition, the Shanghai Museum acquired in 1994 a previously unknown political-military treatise centered on the state of Lu .

As a result of these finds, scholars are now in a position to build a more comprehensive picture of military thinking in the Han and pre-Han periods than has hitherto been possible. We now have enough primary sources at our disposal to trace a line of development for Chinese military philosophy from earliest times through the early Han dynasty and to perceive how this development fits with other intellectual trends of the period.

The present study partakes of this impetus, and also adopts the viewnow widely held among specialiststhat military thought in early China, like other intellectual strands of that era, should not be described as the output of a discrete school of military philosophers (bingjia ).

This problem-centered approach is especially useful in studying military thought in early China because, despite the traditional designation of a military school, opinions and information on military affairs appear in numerous sources, philosophical and otherwise, which were often considered by Chinese scholars in later times as being the outgrowths of specific school traditions. Accordingly, this study intends to construct a history of military thought in early China that is focused not on a military school but on the perennial debate, as it evolved from earliest times through the Western Zhou (ca. 1045771 BCE), Chunqiu (771ca. 475 BCE), and Zhanguo (Warring States) (ca. 475221 BCE) periods, and into the Western Han, regarding the proper uses of civility (

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Military Thought in Early China»

Look at similar books to Military Thought in Early China. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Military Thought in Early China and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.