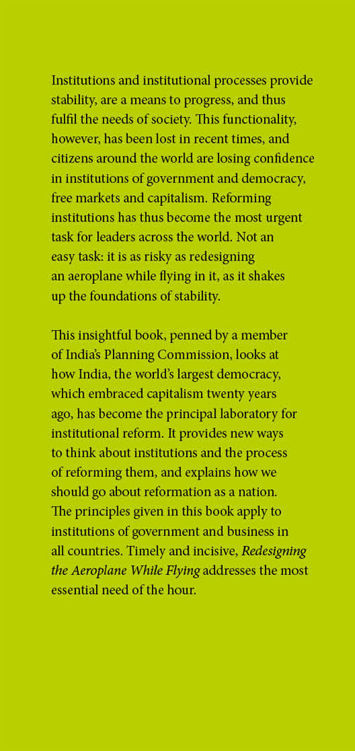

REDESIGNING

THE AEROPLANE

WHILE FLYING

Published in Rainlight by

Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2014

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110002

Sales centres:

Allahabad Bengaluru Chennai

Hyderabad Jaipur Kathmandu

Kolkata Mumbai

Copyright Arun Maira 2014

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First impression 2014

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Printed at [PRINTERS NAME, CITY}

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I have been writing this book for almost twenty years, though it came together only in the last four.

Twenty years ago it became very clear that the principal question I was pursuing in my work was: How can people work more effectively together to produce the outcomes they want? I was then with Arthur D. Little Inc. (ADL) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the oldest consulting company in the world, consulting for business organizations in the USA, Mexico and India. We consulted with NASA and the US government too.

My colleagues in ADL assisted their clients with advice on technology strategy, product and market strategies, and operations management. Many of ADLs clients were demanding that the consultants do not leave a report of what should be done. They must ensure that their recommendations are implemented too. Implementation invariably required that the leadership of the client organization and the people within it do many different things than what they were doing and/or do the same things, but differently. This would require changes in behaviour and changes in mindsetschanging our culture, as many clients put it. Changing cultures, mindsets and behavioursthe how of changeis the hardest part, they would say. Describing what must be done is much easier.

The consultants wanted new toolkits to assist their clients to make the culture changes necessary. The consultants had to change their own mindsets too, to work alongside their clients and coach them through the process of implementation, rather than prescribe solutions to them. My colleagues in ADL turned to me. After some successful client engagements, they urged me to write a book codifying the practice of making change happen. So I wrote my first book, The Accelerating Organization: Embracing the Human Face of Change, along with a colleague, Dr Peter Scott-Morgan, which was published by McGraw Hill in the USA in 1996.

On my return to India in 2000, I was asked to assist many partnerships to perform: partnerships between business organizations; partnerships between government and business organizations; and partnerships between civil society, government and business organizations. Getting people within a client organization, whether business or government, to work together to produce the results they want, is easy as compared to getting people to collaborate across organizational boundaries. In a single organization people are under one command. It is set up for a clear purpose. It has its own rules, written as well as unwritten, that guide its members behaviour. When two or more organizations must work together to create results for a larger system, collaboration amongst their members is much more difficult to obtain. Who is the boss in these initiatives? Which organizations rules will be adopted? Whose culture will prevail?

Authority within an organization can be used to make the structural changes (reporting relationships, incentive systems, etc.) that can induce the changes of behaviour required to implement the new strategy. But when many organizations must work together, it is difficult to change the behaviour of partners who belong to different organizations with such structural changes. Then other means must be found to create the alignment towards the goal, and bring about the necessary cooperation to produce the required results. A deeply shared aspiration for an outcome that all want is one of the means, and agreement about the rules of conduct that all partners will voluntarily adopt is another. My work with partnerships and inquiries into the structures they require for high performance resulted in my next book, Shaping the Future: Aspirational Leadership in India and Beyond, published by John Wiley and Sons in 2002.

Many of the challenges that humanity must address now, such as the degradation of the environment and climate change, persistent inequities within and across countries, and fair rules for global trade, require collaboration across national boundaries. Difficulties in effecting democratic agreements for the improvement of the global commons amongst national governments, each of whom is accountable to its own citizens, have been stalling progress. Methods for arriving at voluntary arrangements are required, in which the mighty and the majority do not smother the weak and the minority.

Indian democracy is founded on a good constitution. India conducts fair and efficient elections on a scale no other country does. Yet the evolution of Indian democracy requires efficient processes for deliberation amongst citizens for the country to move together and faster to produce the outcomes all want. Fully democratic societies require both: constitutions that guarantee rights and due process as well as good, institutionalized processes for conduct of deliberations amongst their members. I was called upon many times, in India and elsewhere, to design and conduct deliberations amongst divergent stakeholders on a variety of issues. I researched the methods used in many countries and described processes for obtaining consensus in my book, Discordant Democrats: Five Steps to Consensus, published by Penguin in 2007.

Two years later, in July 2009, I was unexpectedly invited by the prime minister of India, Dr Manmohan Singh, to serve as a member of the countrys Planning Commission. When the Planning Commission was set up in 1950, the aspiration was to create an institution that would make plans with the people for the people. According to its numerous critics, it has become an ivory tower disconnected from realities on the ground with a bureaucracy that is ineffectual in inducing change in the country. One of the tasks the PM gave me on the side, in addition to my official responsibilities, was to consider how the Planning Commission could be reformed to become a system reforms commission and an essay in persuasion as it should be, rather than the budget-allocating, plan-formulating and target-setting organization it has become.

For the past four years, from Indias cockpitthe national Planning CommissionI could get a perspective of the changes sweeping through India. Every year, chief ministers of all Indian states come to the Planning Commission to explain the progress their states are making and the challenges they are facing. The Planning Commission oversees the central government ministries too, and all sectors of the Indian economy. When it prepared the countrys 12th Five Year Plan in 2012, it deployed a process for the first time to listen widely to the people of the country. Almost a thousand civil society organizations representing all sections of Indian society and dozens of business associations participated in an exercise to gather the views of citizens about what mattered most to them and the opportunities they saw for change in the country. With these myriad inputs from many perspectives, and using techniques of systems analysis and scenario planning, one could see the principal forces that are shaping India. And one could hear the signals beneath the deep rumbling of Indian democracy.