The Strange Alchemy of Life and Law

The Strange Alchemy of Life and Law

JUSTICE ALBIE SACHS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX 2 6 DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Albie Sachs, 2009

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Crown copyright material is reproduced under Class Licence

Number C01P0000148 with the permission of OPSI

and the Queens Printer for Scotland

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

Typeset by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

ISBN 9780199571796

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

The lovely little boy that Vanessa and I brought into the world two years ago has to our delight just used the word why? If one day he wants to know why we named him Oliver, why his Daddy has one arm, and why his Daddy is called a Judge, he can find the answers in this book.

About the Author

On turning six, during World War II, Albie Sachs received a card from his father expressing the wish that he would grow up to be a soldier in the fight for liberation.

His career in human rights activism started at the age of 17, when as a second year law student at the University of Cape Town, he took part in the Defiance of Unjust Laws Campaign. Three years later he attended the Congress of the People at Kliptown where the Freedom Charter was adopted. He started practice as an advocate at the Cape Bar aged 21. The bulk of his work involved defending people charged under racist statutes and repressive security laws. He himself was raided by the security police, subjected to banning orders restricting his movement and eventually placed in solitary confinement for two prolonged spells of detention.

In 1966 he went into exile. After spending eleven years doing a doctorate at Sussex and teaching law at Southampton he worked for a further eleven years in Mozambique as law professor and legal researcher. In 1988 he was seriously injured by a bomb placed in his car by South African security agents, losing an arm and the sight of an eye.

During the 1980s working closely with Oliver Tambo, leader of the ANC in exile, he helped draft the organizations Code of Conduct, as well as its statutes. Once he had returned to health after the car bomb, he devoted himself to preparations for a new democratic Constitution for South Africa. In 1990 he returned home and as a member of the Constitutional Committee and the National Executive of the ANC took part in the negotiations which led to South Africa becoming a constitutional democracy. After the first democratic election in 1994 he was appointed by President Nelson Mandela to serve on the newly established Constitutional Court.

He has travelled to many countries sharing South African experience in healing divided societies, been engaged in the sphere of art and architecture, and played an active role in the development of the Constitutional Court building and its art collection on the site of the Old Fort Prison in Johannesburg. Author of many books, his Jail Diary was dramatized for the Royal Shakespeare Company and broadcast by the BBC.

Honorary Bencher of Lincolns Inn, he is an Appeals Commissioner of the International Cricket Council.

The Man Who Sang and the Woman Who Kept Silent

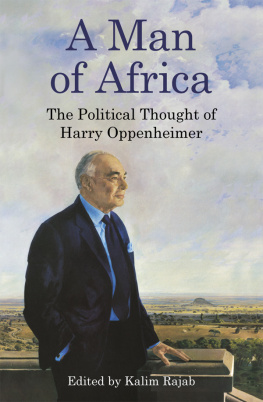

The work on the cover of this book commemorates the courage of Phila Ndwandwe and Harald Sefola whose deaths during the Struggle were described to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission by their killers.

Phila Ndwandwe was shot by the security police after being kept naked for weeks in an attempt to make her inform on her comrades. She preserved her dignity by making panties out of a blue plastic bag. This garment was found wrapped around her pelvis when she was exhumed. She simply would not talk, one of the policeman involved in her death testified. God... she was brave.

Harald Sefola was electrocuted with two comrades in a field outside Witbank. While waiting to die he requested to sing Nkosi Sikelel iAfrika. His killer recalled, he was a very brave man who believed strongly in what he was doing.

I wept when I heard Philas story, saying to myself, I wish I could make you a dress. Acting on this childlike response, I collected discarded blue plastic bags that I sewed into a dress. On its skirt I painted this letter:

Sister, a plastic bag may not be the whole armour of God, but you were wrestling with flesh and blood, and against powers, against the rulers of darkness, against spiritual wickedness in sordid places. Your weapons were your silence and a piece of rubbish. Finding that bag and wearing it until you were disinterred is such a frugal, commonsensical, house-wifely thing to do, an ordinary act... At some level you shamed your captors, and they did not compound their abuse of you by stripping you a second time. Yet they killed you. We only know your story because a sniggering man remembered how brave you were. Memorials to your courage are everywhere; they blow about in the streets and drift on the tide and cling to thorn-bushes. This dress is made from some of them. Hambe kahle. Umkhonto.

The dress, swinging on its hanger in the breeze, reminded me of the drapery on the Victory of Samothrace in the Louvre. So I painted a local Victory figure moving through imprisoning grids of wire accompanied by a hyenaat once a predator and a scavenger.

Justice Albie Sachs saw these pieces and a painting of three braziers I had made in memory of Sefola and his friends. He suggested I combine Philas dress and the braziers into a commemorative work. Eventually the dress, the dress painting, and the second larger canvas were all placed together in the South African Constitutional Court.

Having the opportunity to honour the man who sang and the woman who kept silent has been a privilege, but it leaves me with an abiding sense of shame.

Judith Mason

Preface

This book should be of huge interest to the international judicial community and everyone else who is interested in justice. It gives a rare insight into Albie Sachs unique approach to justice. Anybody of the many people who, like myself, have had the privilege of spending time in his company or listened to him giving lectures, will find his personal qualities leaping out of every page. However, it is those judges (not all judges) who believe judging is much more than merely deciding cases who will obtain the greatest benefit and pleasure from what he has written.

Next page