As with any work in a complex area, there are many people who have contributed to my understanding of the topic of non-lethal weapons and helped provide a platform from which to speak. They range from senior generals, admirals, and policy makers to bench scientists. In developing the field and writing this book, I owe thanks to Admiral David Jeremiah, General E. C. Shy Meyer, General Lloyd Fig Newton, General Glenn Otis, Admiral Bill Owens, General John Sheehan, General Carl Stiner, General Anthony Zinni, Lieutenant General Bud Forster, Lieutenant General Larry Skibbie, Lieutenant General Martin Steele, Lieutenant General Gordon Sumner, Vice Admiral Ron Thunman, Lieutenant General Dick Trefry, Major General Cecil Powell, Malcolm Wiener, Les Gelb, Edward Teller, George Singley, Alvin Toffler, Chips Stewart, Earl Rubright, David Boyd, Bob Tolle, Ray Downs, Kit Green, John McMahon, Harvey Sapolsky, Dean Judd, John Browne, Allen Murashige, John Petersen, Colonel John Warden, Colonel Jamie Gough, Colonel John Barry, Captain Dave Carroll, Robert Kupperman, Ben Rich, Don Henry, Charles Swett, Hildi Libby and her staff at ARDEC, Ed Scannell, Steve Small, Tom Starke, Oke Shannon, Jerry Perrizo, Andy Andrews, Marty Piltch, Johndale Solem, Lieutenant Sid Heal, Master Sergeant Bud Schiff, Scott Kinkead, Pat Unkefer, Craig Taylor, Paul Kozemchak, Major John Klaaren, Major Ron Mitchell, Captain Stan Coerr, Jamie Cuadros, Bob Reinovsky, Keith Gardner, Susan Hudson, Nelson Jackson, Joe Hylan, Ron Pandolfi, Ted Handle, Marc Alexander, Steve Scott, Dennis Richburg, Jim Richardson, Jim Danneskiold, Clay Easterly, Arnis Mangolds, John Dering, Ainslie Young, John Meier, all the members of the NATO-AGARD study teams for AAS-40 and AAS-43, Colonel Andy Mazzara and his entire staff at the Joint Non-Lethal Weapons Directorate, and the others who have supported the non-lethal weapons effort.

To my friend Tom Clancy I am especially indebted for the foreword to this book, our discussions, his encouragement, and for including non-lethal weaponswhere appropriatein his books. Through his novels, the concepts have reached far more people than by way of any of the numerous technical briefings we have given.

In addition, I want to thank Daniel Tomcheff for correcting my early manuscript, my editors at St. Martins Press, Tom Burke and Pete Wolverton, as well as my publisher, Tom Dunne. I also thank my agent and longtime friend Ralph Blum for his efforts.

To my wife, Victoria, goes special recognition, for she has patiently endured the necessary conferences and separations, plus my frustrations in drafting this work.

A MODEL FOR UNDERSTANDING SOCIAL ORGANIZATIONS

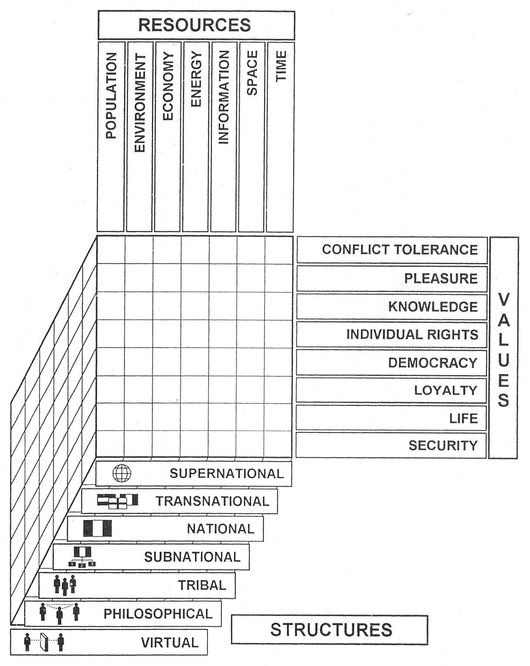

The basis for future societal organization may be described by examining three factors. They are structure, resources, and values as depicted on the axes in Figure 1. Each axis addresses one component. The vertical axis describes the possible institutional structures from large groupings to smaller ones. Any given organization will have some form of structure that identifies it. Some of the structures may be different from what we have previously experienced in social organizations. The horizontal axis depicts the resource categories that may be available to those organizations. It is critical to know what resources are available to an organization at any given time. And the diagonal axis represents the institutional values that are held by each organization. Organizations will allocate resources based on their values and beliefs. It is a common mistake to assume that there is a single logical method by which societies will organize. That is the rational man approach based on traditional Western values. It has been demonstrated repeatedly that foreign countries do not always respond as we predict. Though frequently labeled crazy, it is more likely that they have applied different values in arriving at their solutions to problems.

While many have spoken to these subjects, this model for thinking about social organization has not been previously available. It provides a method whereby analysts can more accurately predict the courses of action that potential adversaries may take.

Structures . The possible structures run from the currently dominant unit, the nation-state , to commonly accepted supernational and subnational entities, but may include emerging concepts such as virtual organizations. Supernational organizations would include the European Union, NAFTA, and will probably see the rise of a Pacific Rim economic bloc in the near future. Transnational organizations have previously been addressed but can include legitimate economic entities with sufficient wealth to be able to become players in regional affairs. Subnational elements include religious and ethnic groups that are normally collocated with others. Some come from failed states, while others are the product of previous geographic subdivisions. Too frequently, prior geographic boundaries were drawn based on conquest or cartographers whims and did not properly account for the demographics or sentiments of the indigenous population.

The Basis of Societal Structures

Virtual organizations are ones that usually have no contiguous physical structure, and with whom affiliation is based on an ideological and voluntary basis. Burgeoning information technology will enable such groups to form, conduct business, and disestablish, leaving little trace of their physical existence. The importance of such virtual organizations is their ability to generate ideas and get them inculcated into more mainstream organizations. They may obtain power based on the strength of their ideas. History has proven that ideas can be more powerful than physical structures. It is possible for virtual groups to form without true identities being revealed. A clever leader may then stimulate individuals of the group to act in a manner that may be contrary to national interests, then simply disappear. In such a case, our ability to retaliate with force would be severely limited.

Resources . All organizations have resources, some of which are listed in the figure on page 219. In the future, there may be some new concepts about what constitutes resources available to a social group. Certainly natural resources available from the environment will continue to play an important role. They may be placed in a broader context than materials found within specified geographic boundaries. The historic context for rules regarding these resources can be found in water rights and rules of the high seas. More recently, the international community has addressed the use of outer space and established accepted rules for use of this common resource. Emerging trends hold international interests in environmental issues previously believed to be internal affairs. For example, can a country decimate its own rain forest which produces oxygen for the globe?

Other traditional resources include the population of a country and its economy. These concepts, too, are changing, based on migration and the globalization of the economy. Information has become the coin-of-the-realm in many organizations. Clearly, information transcends institutional and geographic boundaries in a manner that is difficult to restrict. Attempts to codify intellectual property rights seem doomed to the perpetual advances in related technologies but remain at the heart of fierce international diplomacy and debate.

The disproportionate use of energy by developed nations is an intensely debated issue. Energy use has been traditionally viewed as available based on the ability of the user to pay. The collateral costs, i.e., contamination, have until recently been largely disregarded. A new view of energy rights is likely to emerge and add complexity to societal structures.