First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Glynis Cooper 2015

ISBN: 978 1 47382 171 2

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47385 511 3

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47385 515 1

The right of Glynis Cooper to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including

photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in Times New Roman

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery,

Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways,

Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, and Claymore Press,

Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

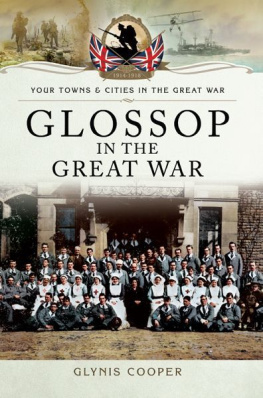

This book is dedicated to Joseph Cooper (1884-1972) of Glossop who served with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in the Dardanelles and Palestine during the Great War, to the 300 men from Glossop and 160 men from Hadfield who made the supreme sacrifice, and to all those from Glossop and its townships who fought so valiantly in the war to end all wars, 1914-1918.

Contents

Acknowledgements

With grateful acknowledgement to Pen & Sword for initiating and publishing this book, to the helpful and long-suffering staff of Glossop Library whose interest and assistance in this project proved invaluable, and to family and friends for accepting without rancour being totally ignored while I completed this book. Thank you everyone.

Chapter One

1914

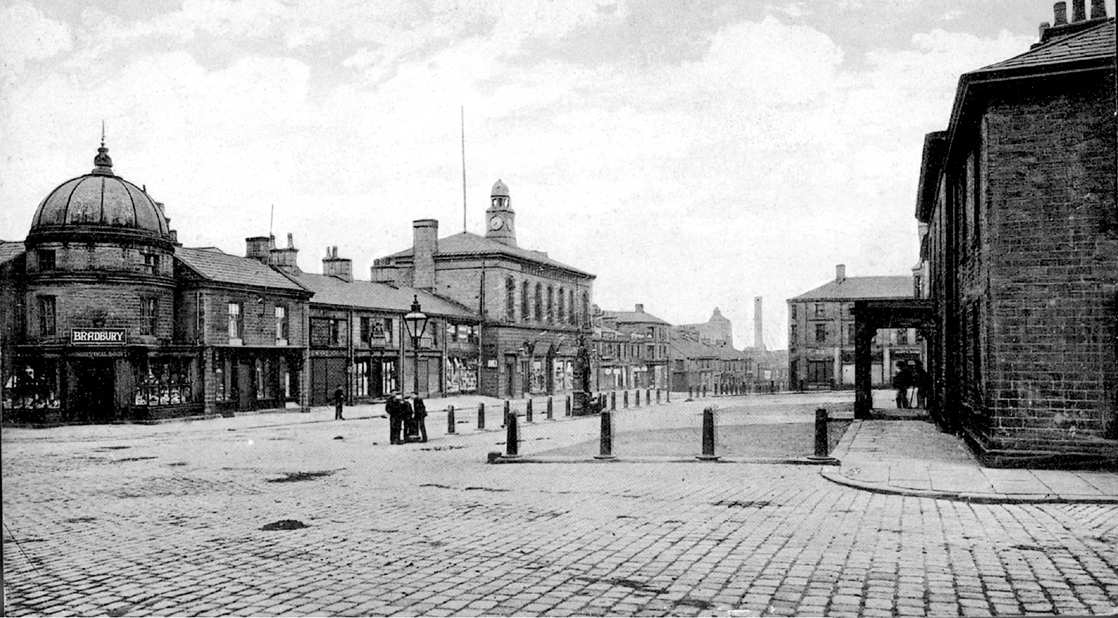

GLOSSOP WAS, AND still remains to some extent, a typical small northern mill-town snuggled into the north-western corner of Derbyshire about 12 miles due east of Manchester. In 1902 the town was described: Glossopdale Rural District Council consists of some places of a more urban character, separated by other portions of a strictly rural and agricultural character[]a mixture of farm workers and cotton workers. At the outbreak of the Great War, on 4th August 1914, most of Glossopdale was owned by Lord Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, and had been since the seventeenth century. The area originally consisted of ten small townships. The oldest of these were Glossop to the east (now known as Old Glossop), Hadfield and Padfield to the west, and Whitfield to the south. The other townships were Chunal, Gamesley, Dinting, Simmondley, Charlesworth and Ludworth. Until the coming of the Industrial Revolution, the whole of Glossopdale was a sleepy farming community, a Roman fort its main claim to historical distinction. Stone for building was quarried locally and there was opencast mining for coal. The coal mines at Simmondley were not particularly deep but they were quite extensive and had, at one time, supplied Dinting Printworks (owned by the family of Beatrix Potter, until the early years of the twentieth century) with all their necessary fuel.

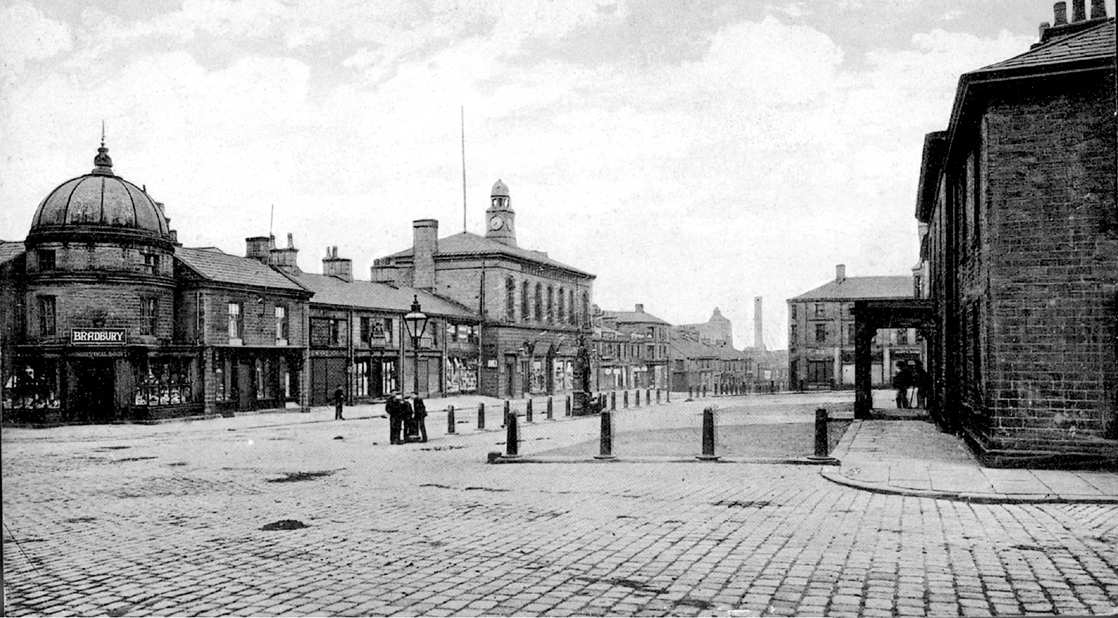

The change in the local landscape, which began at the end of the eighteenth century, from farmscape to millscape, was rapid and bewildering. Until about 1780 Glossop had been remote and insular. Then the Industrial Revolution came, followed in 1845 by the building of the railway linking Glossop to Manchester and Sheffield. Old ways, old traditions, old beliefs and the old life became subsumed by the noise and smoke and industry of the dark Satanic mills, a myriad of tall black chimneys lancing the pretty valley like pins in a pin cushion. The town migrated, mostly to the west, as demand for land on which to build textile mills and workers cottages increased. The Town Hall was built where High Street East met High Street West, with a market place to the rear. Butchers, grocers and drapers shops lined the streets and there were working mens clubs and a large number of pubs. Several mill owners contracted with local farmers for exclusive supplies of food grown, which they then sold on to their workers at discounted rates. Although Glossop fared much better in some ways than a lot of its neighbours, because it was surrounded by hills, moorlands, a number of farms and open countryside, life was still hard, grim and dirty for many of its people.

If there had been unease in the air of national and international politics during the first few months of 1914, the local Glossop paper had not picked up on it. Although the town had become an industrial cotton-millscape, its psyche remained insular, and parochial matters were always of much greater interest than news from the outside world. During much of March and April the main concern was the death and funeral of Mrs Anne Kershaw-Wood, a notable Glossop lady and a benefactress of the town. Letters home to the Glossop newspaper were published from a number of former townspeople who had emigrated to Canada. There were stories of union disputes and possible short-time working in the local weaving trade, sports fixtures and news from the surrounding villages. Although motoring was still in its infancy, Glossop possessed one of the most modern and up to date garages in the country[]the Glossop Motor Company Ltd. The proprietor was Mr Walter Fielding, a Glossop man who had learned his trade across the pond, and who had returned to his native town to dispense the benefits of his experience. Interest in the motoring industry was growing rapidly and business was good. The Glossop Motor Company premises were on Arundel Street and they still house a motor trade business today. Local events and the cost of living and new labour saving devices were the main topics of conversation. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand scarcely merited a mention. Even in late July the talk was of the local effects of Lloyd Georges budget and how to wash a tub of clothes in four minutes with no boiling, no rubbing and no scrubbing.

Glossop Town Centre (urban aspect of Glossop) on the eve of the Great War, c1914

However, a tense and increasingly violent political drama was being played out on the European stage. On 28 June, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife, Duchess Sophie, were assassinated in Sarajevo (a town in Bosnia which, at that time, was part of Austria-Hungary) by a member of the Serbian nationalist organisation, the Black Hand. A week later the German kaiser, Wilhelm, offered Austria-Hungarian and German support for a war against Serbia. There had been a number of political tensions caused by competition between Austria-Hungary, Serbia and Russia for territory in the Balkan States. Bosnia did not wish to be part of Austria-Hungary and the Serbs wanted to take over Bosnia for themselves. On 23 July, Austria-Hungary gave the Serbs an ultimatum, which they largely ignored, and on 28 July, Austria-Hungary declared war against the Serbs. To everyones surprise Russia mobilised troops. On 31 July, Germany warned Russia about mobilising troops but the Russians insisted that their mobilisation was directed at Austria-Hungary alone. Clearly not believing this, the Germans declared war on Russia the following day and then signed a secret alliance treaty with the Ottoman Empire. The next day, 2 August, Germany invaded Luxembourg and the first military skirmish on the Western Front took place at Joncherey. On 3 August, Germany declared war on France and demanded that Belgium allowed German arms to reach the French border. The Belgians, as per their neutral status, refused to do so, and on 4 August, Germany invaded Belgium. Britain protested at this violation of Belgian neutrality, which was guaranteed by a treaty. The German chancellor dismissed British objections saying that the treaty was just a scrap of paper. Incensed, the British declared war on Germany. The following day the Ottomans closed the Dardanelles and the scene was set for the greatest war in history.

Next page