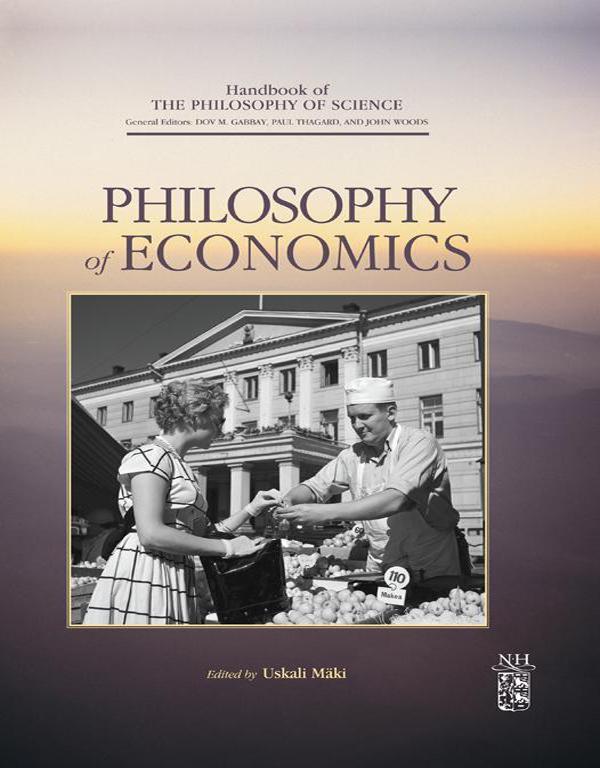

Handbook of the Philosophy of Science Volume 13

Philosophy of Economics

Edited by

Uskali Mki

Director, Academy of Finland Centre of Excellence in the Philosophy of the Social Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland, Department of Political and Economic Studies

North Holland is an imprint of Elsevier

The Boulevard, Langford lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK

Radarweg 29, PO Box 211, 1000 AE Amsterdam, The Netherlands

First edition 2012

Copyright 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher Permissions may be sought directly from Elseviers Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone (+44) (0) 1865 843830; fax (+44) (0) 1865 853333; email: permissions@elsevier.com. Alternatively you can submit your request online by visiting the Elsevier web site at http://elsevier.com/locate/permissions, and selecting Obtaining permission to use Elsevier material

Notice

No responsibility is assumed by the publisher for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions or ideas contained in the material herein. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, in particular, independent verification of diagnoses and drug dosages should be made

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN: 978-0-444-51676-3

For information on all North Holland publications visit our web site at www.elsevierdirect.com

Printed and bound in Great Britain

12 13 14 15 16 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For TINT

General Preface

Dov Gabbay, Paul Thagard and John Woods

Whenever science operates at the cutting edge of what is known, it invariably runs into philosophical issues about the nature of knowledge and reality. Scientific controversies raise such questions as the relation of theory and experiment, the nature of explanation, and the extent to which science can approximate to the truth. Within particular sciences, special concerns arise about what exists and how it can be known, for example in physics about the nature of space and time, and in psychology about the nature of consciousness. Hence the philosophy of science is an essential part of the scientific investigation of the world.

In recent decades, philosophy of science has become an increasingly central part of philosophy in general. Although there are still philosophers who think that theories of knowledge and reality can be developed by pure reflection, much current philosophical work finds it necessary and valuable to take into account relevant scientific findings. For example, the philosophy of mind is now closely tied to empirical psychology, and political theory often intersects with economics. Thus philosophy of science provides a valuable bridge between philosophical and scientific inquiry.

More and more, the philosophy of science concerns itself not just with general issues about the nature and validity of science, but especially with particular issues that arise in specific sciences. Accordingly, we have organized this Handbook into many volumes reflecting the full range of current research in the philosophy of science. We invited volume editors who are fully involved in the specific sciences, and are delighted that they have solicited contributions by scientifically-informed philosophers and (in a few cases) philosophically-informed scientists. The result is the most comprehensive review ever provided of the philosophy of science.

Here are the volumes in the Handbook:

Philosophy of Science: Focal Issues, edited by Theo Kuipers.

Philosophy of Physics, edited by Jeremy Butterfield and John Earman.

Philosophy of Biology, edited by Mohan Matthen and Christopher Stephens.

Philosophy of Mathematics, edited by Andrew Irvine.

Philosophy of Logic, edited by Dale Jacquette.

Philosophy of Chemistry, edited by Andrea Woody, Robin Hendry and Paul Needham.

Philosophy of Statistics, edited by Prasanta S. Bandyopadhyay and Malcolm Forster.

Philosophy of Information, edited by Pieter Adriaans and Johan van Benthem.

Philosophy of Technology and Engineering Sciences, edited by Anthonie Meijers.

Philosophy of Complex Systems, edited by Cliff Hooker.

Philosophy of Ecology, edited by Bryson Brown, Kent Peacock and Kevin de Laplante.

Philosophy of Psychology and Cognitive Science, edited by Paul Thagard.

Philosophy of Economics, edited by Uskali Mki.

Philosophy of Linguistics, edited by Ruth Kempson, Tim Fernando and Nicholas Asher.

Philosophy of Anthropology and Sociology, edited by Stephen Turner and Mark Risjord.

Philosophy of Medicine, edited by Fred Gifford.

Details about the contents and publishing schedule of the volumes can be found at http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/bookseriesdescription.cws_home/BS_HPHS/description

As general editors, we are extremely grateful to the volume editors for arranging such a distinguished array of contributors and for managing their contributions. Production of these volumes has been a huge enterprise, and our warmest thanks go to Jane Spurr and Carol Woods for putting them together. Thanks also to Lauren Schulz and Derek Coleman at Elsevier for their support and direction.

Preface

Uskali Mki

In the course of its history, economics has been variously defined, including as the study of the consequences of actors selfish pursuit of maximum wealth; and more abstractly in terms of economizing or getting the most for the least; in terms of exchange in the market; in terms of whatever can be identified by the measuring rod of money; and in terms of rational choice faced with the scarcity of means in relation to the multiplicity of ends.

Even if conceived as a science of choice, only a small proportion of economic explanation is designed to explain episodes of individual behaviour. Most of it seeks to account for aggregate or social level phenomena, patterns, or regularities that have been observed statistically or through ordinary experience. The highly idealized and formalized models built for this purpose depict various kinds of so-cial typically market-like invisible hand mechanisms that mediate between individual choices and collective outcomes as their unintended consequences. Such outcomes are represented as equilibrium positions, and their explanation or pre-diction often does not describe the process whereby the equilibria are attained. Adding a normative dimension to the explanatory use of social mechanisms, these outcomes have been portrayed either as generous such as in the Mandevillean idea of private vices, public virtues and in contemporary welfare theorems, or else as undesirable products of invisible backhand mechanisms of prisoners dilemma type.