Graham - We do not fear anarchy, we invoke it : the First International and the origins of the anarchist movement

Here you can read online Graham - We do not fear anarchy, we invoke it : the First International and the origins of the anarchist movement full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Europe, year: 2015, publisher: AK Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

We do not fear anarchy, we invoke it : the First International and the origins of the anarchist movement: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "We do not fear anarchy, we invoke it : the First International and the origins of the anarchist movement" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

From 1864 to 1876, socialists, communists, trade unionists, and anarchists synthesized a growing body of anticapitalist thought through participation in the First Internationala body devoted to uniting left-wing radical tendencies of the time. Often remembered for the historic fights between Karl Marx and Michael Bakunin, the debates and experimentation during the International helped to refine and focus anarchist ideas into a doctrine of international working class self-liberation.

This book is a breath of fresh air in a stuffy room. At long last, anarchists enter the history of socialism by the main door!

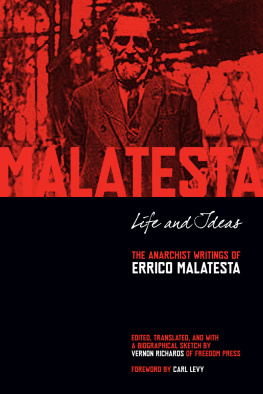

Davide Turcato, author of Making Sense of Anarchism: The Experiments with Revolution of Errico Malatesta, Italian Exile in London, 18891900

Brimming with thought and feeling, richly textured, and not shy of judgment, Grahams book marshals a compelling argument and issues a provocative invitation to revisitor perhaps to explore anewthe story, the struggles, and the persisting ramifications of this pioneering International.

Wayne Thorpe, author of The Workers Themselves: Revolutionary Syndicalism and International Labour, 19131923

With impressive and careful scholarship, Robert Graham guides us on a complex journey that reflects his command of the material and his ability to express it in a clear and straightforward way. If you were to think this is some dry history book, you couldnt be more wrong.

Barry Pateman, historian and archivist with the Kate Sharpley Library

Robert Graham has been writing about anarchism for thirty years. He recently edited the three-volume collection Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas.

Graham: author's other books

Who wrote We do not fear anarchy, we invoke it : the First International and the origins of the anarchist movement? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.