Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2015 by Barbara Kellerman. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Special discounts for bulk quantities of Stanford Business Books are available to corporations, professional associations, and other organizations. For details and discount information, contact the special sales department of Stanford University Press. Tel: (650) 736-1782, Fax: (650) 736-1784

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

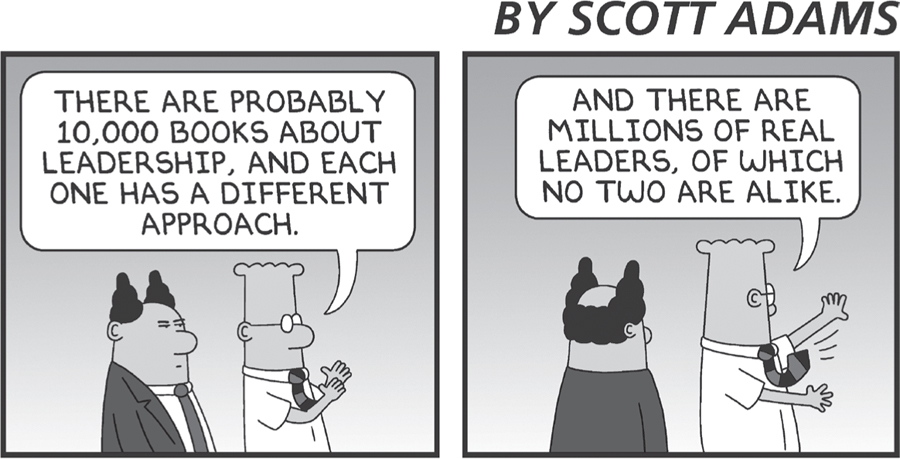

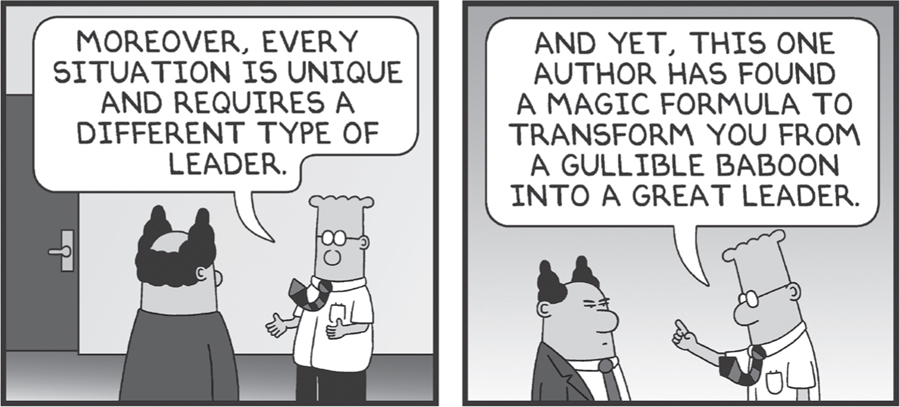

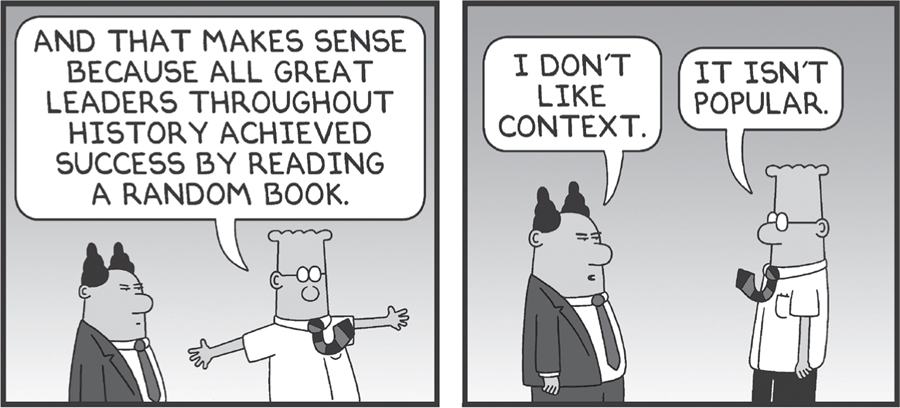

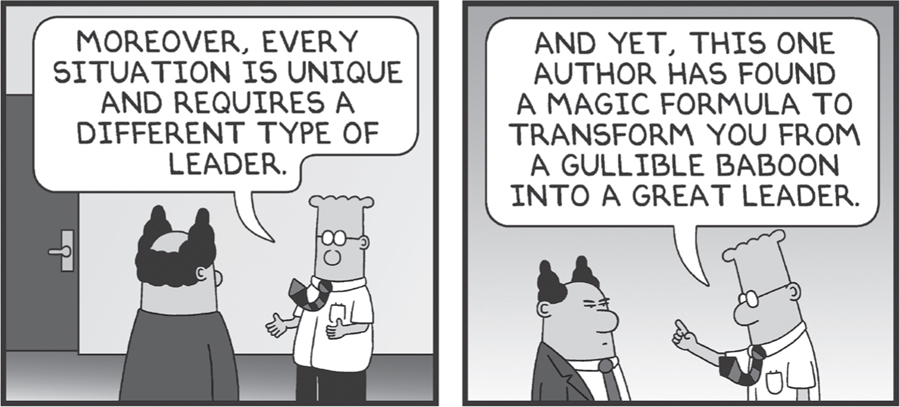

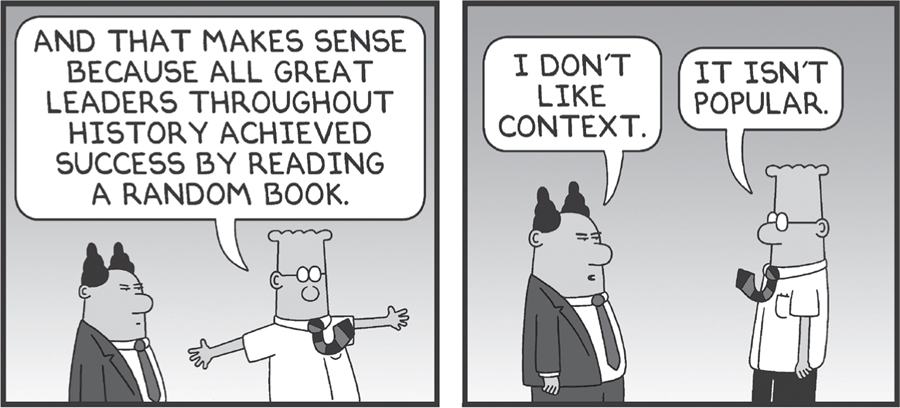

DILBERT 2013 Scott Adams. Used by permission of UNIVERSAL UCLICK.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kellerman, Barbara, author.

Hard times : leadership in America / Barbara Kellerman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8047-9235-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. LeadershipUnited States. 2. Political leadershipUnited States. I. Title.

HD57.7.K4478 2014

303.3'40973dc23

2014021439

ISBN 978-0-8047-9301-8 (electronic)

Typeset by Classic Typography in 11/15 Minion Pro

HARD TIMES

LEADERSHIP IN AMERICA

BARBARA KELLERMAN

STANFORD BUSINESS BOOKS

An Imprint of Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

For Ellen Greenwald and Cathy Utz...

Forever Family

To see what is in front of ones nose needs a constant struggle.

George Orwell

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My thanks to Laura Aguilar, Margo Beth Fleming, Kenneth Greenwald, Sasanka Jinadasa, Klara Kabadian, Mike Leveriza, Thomas Patterson, Todd Pittinsky, and Thomas Wren.

PROLOGUE

Whats Been Lost?

WHATS BEEN LOST in the discussions on leadershipin the infinite number of discussions on leadershipis context. I refer not to context that is proximate, such as a particular group or organization, but to context that is distal, to the larger context within which leadership and yes, also followership, necessarily are situated.

This book will fill in that all-important missing piece. It is not a how-to booka book about how to be a leader. Instead it is a how-to-think-like-a-leader workbook that provides a clear, cogent corrective to the thousands of other instructions already available.Hard Times is a checklist of what you need to know about context if you want to lead in the United States of America in the second decade of the twenty-first century. It is not a handy-dandy manual on what to do and how to do it, for the specifics of the situation determine the particulars. What it does do is make meaning of leadership in America in a wholly new and different way. What it does do is provide every American leader with a framework for seeing the setting within which work gets done.

Anyone who knows my work knows that sometimes I am a contrarian. I have written extensively about leadership, but deviated from the norm in at least four ways. First, I focus as much on bad leadership as on good leadership. Second, I think followers every bit as important as leaders. Third, I am skeptical of what I call the leadership industrymy catchall term for the now countless leadership centers, institutes, programs, courses, seminars, workshops, experiences, trainers, books, blogs, articles, websites, webinars, videos, conferences, consultants, and coaches claiming to teach people, usually for money, much money, how to lead.

Finally, frankly, I take issue with Americas relentless leader-centrism, with Americas obsessive fixation on leaders at the expense of followers and at the expense of the context within which both necessarily are situated. Instead I argue for a more complete conception of how change is created. I have come to see leadership as a system consisting of three moving parts, each of which is equally important and each of which impinges equally on the other two. The first is the Leader. The second is the Follower. And the third is the Contextthe focus of this book.

If we accept the proposition that leadership is a system, the leadership industry should be as invested in followers as it is in leaders, and as focused on context as on only some of the leading actors. But it is not. Instead it is fixated, still, laser-like, on leaders. This explains why leadership learning is biased toward self-improvement, skill development, and self-awarenesstoward instilling competence and, possibly, character in a single individual. We attempt to develop individual capacities such as communicating and negotiating, and we attempt to develop individual characteristics such as authenticity and integrity. The relentless implication is that what matters most is internal, individual change, not external, collective change. Put another way, our study, practice, and promotion of leadership are inner-directed, not outer- or other-directed. They are leader-centric and solipsistic.

Its not that we ignore context altogether. Quite the contrary: leaders are taught to take context into account. But the context they are taught to take into account is circumscribed. It is context as proximatecontext of interest and importance to the leader, not context of interest and importance more generally. Some prominent leadership experts have, for example, properly and pointedly stressed the value of diagnosing the situation, of stepping back to gain perspective. But still, they keep close. Their eyes are trained on the context that immediately pertainswhich is your companys structures, culture and defaultsrather than on the more expansive context within which the organization (the company) itself is located.

Followers, when they even enter the picture at all, are drawn similarly narrowly, as opposed to more broadly. Wharton School professor The principles of his template include fostering teamwork, building interdependence, and coaching individuals to reach the next level. However his principles are drawn from his particular populationlarge companies, financial institutions, and his classroom at the Wharton School. They are not drawn from the larger context within which people in the private sector also are situated.

Let me be clear: I have no quarrel with this sort of proximate approach. The question I raise is not whether it is necessary, but whether it is sufficient. The leadership industry has a problema screamingly obvious one. It has failed over its roughly forty-year history to in any major, meaningful, measurable way improve the human condition. In fact, the rise of leadership as an object of our collective fascination has coincided precisely with the decline of leadership in our collective estimation. Private sector leaders are widely viewed as greedy to the point of being corrupt. Public sector leaders are seen as hapless to the point of being inept. And leaders previously regarded as virtually sacrosanctreligious leaders, for example, and military leadershave been diminished and even demeaned.

Next page