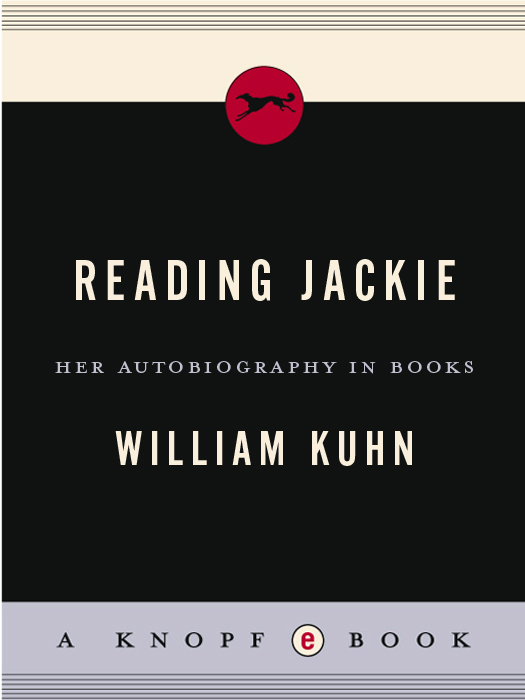

ALSO BY WILLIAM KUHN

Democratic Royalism:

The Transformation of the British Monarchy, 18611914

Henry and Mary Ponsonby: Life at the Court of Queen Victoria

The Politics of Pleasure: A Portrait of Benjamin Disraeli

Copyright 2010 by William Kuhn

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Limited, Toronto.

www.nanatalese.com

Doubleday is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Estate of C.P. Cavafy: Excerpt from Ithaka by C.P. Cavafy, copyright by C.P. Cavafy.

Reprinted by permission of the Estate of C.P Cavafy

c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd.,

20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN.

The Groton School: Excerpt from Growing Up with Jackie, My Memories 19411953 by Hugh D. Auchincloss III (Groton School Quarterly, vol. LX, no 2, May 1998).

Reprinted by permission of The Groton School.

Ms. Magazine: Excerpt from On Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis by Gloria Steinem (Ms., March 1979).

Reprinted by permission of Ms. Magazine.

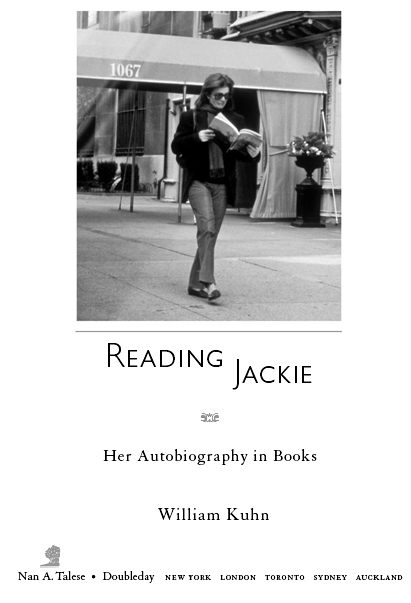

: Paul Adao / New York News Service

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kuhn, William M.

Reading Jackie : her autobiography in books / William Kuhn. 1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Onassis, Jacqueline Kennedy, 19291994. 2. Book editorsUnited StatesBiography. 3. EditorsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Presidents spousesUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

PN149.9.O53K84 2010

070.509492dc22

[B] 2010032689

eISBN: 978-0-385-53100-9

v3.1_r1

for Emma Riva

and

for Maria Carrig

Contents

Authors Note

I considered calling her Mrs. Kennedy or Mrs. Onassis, the names she might have preferred herself. I also wanted to avoid the inequality of the old convention whereby women were called by their first names and men by their last names. However, as this book explores what she did on her own, after both her husbands died, it didnt seem quite right to refer to her by their names. Although aware of its limitations and of an implication of familiarity I dont intend, Ive called her Jackie, not only for clarity but because its the way most people know her, because its simpler, and because its the way we speak now.

PROLOGUE

In the end the diagnosis came as something of a relief. She had been feeling unwell for so long and didnt know what it was. She had had flu symptoms ever since the previous summer, when she and her companion Maurice Tempelsman had traveled in southern France. They went not to the beaches and shops along the Riviera where everyone imagined she liked to go, but along the Rhne, to the Roman towns at Arles and Avignon. She wrote a postcard to one of her authors, Peter Ss, saying shed been to Roussillon, where they made a famous paint out of local clay and ochre-colored pigment. Ss was also a painter and an illustrator, and she loved talking to him about art. She didnt tell him that she hadnt felt quite right. She expected all that to clear up. Then, during the fall, when she didnt improve, and in the Caribbean around Christmas, when she was worse, she knew she needed some help. When the doctors told her in January 1994 that she had non-Hodgkins lymphoma, it wasnt the end of the world. Yes, it was cancer. But they thought theyd found it early enough to treat it and make her well. At least she knew what she was dealing with. She could read about it in a book. The doctors recommended chemotherapy, and even that wasnt too bad. She told Arthur Schlesinger, once Jack Kennedys special assistant, now a distinguished historian and her old friend, that she could take a book along and read as the drugs dripped into her arm. The woman who had taught a nation what it was like to have courage had an instinct not to overdramatize things, to play it low-key, to stay upbeat. She lost her hair. Well, she would wear a wig. She sometimes didnt feel like going into her office at Doubleday. Well, she could telephone her authors from home.

In the spring of 1994, Steve Rubin, the head of Doubleday, called in Jackie, who was now a senior editor, to say that hed give her a sabbatical until she felt better. She saw her old friend Nancy Tuckerman and asked her, Nancy, whats a sabbatical? The two women had known each other since fifth grade at the Chapin School in New York. Theyd also been roommates at Miss Porters School in Farmington, Connecticut. Tuckerman had served as White House social secretary and worked for Aristotle Onassis at Olympic Airways, where she helped to found the first New York City Marathon with the airlines sponsorship, and now her office was right next to Jackies at Doubleday. Tuckerman was used to Jackies innocent way of asking a question in order to raise a laugh. She had seen her do this to the teachers at school and be sent to the principals office. So now, faced with the question Whats a sabbatical? she replied, Jackie, Ive worked partly for you for years, and youve never given me a sabbatical, so how should I know what a sabbatical is?

There were scenes at the hospital. Jackie suffered from side effects of the chemotherapy. She had to go back to New York HospitalCornell Medical Center, where she was being treated for an ulcer. There they discovered that the cancer had spread and more invasive methods of administering chemotherapy had to be tried. During one of her hospital stays, former president Nixon, now living in retirement part of the year in New Jersey, had a stroke and was sent to the same hospital. Tuckerman, as Jackies spokesperson, fielded calls from the press. A young voice from a tabloid called to ask, Could Mrs. Onassis and President Nixon be photographed together? The suggestion that two seriously ill people should be wheeled into a common room for a photo op was grotesque, and also a little funny. Jackie had never been able to stand Dick Nixon, and once when he called her because he wanted her permission to publish a photograph of them together in his memoirs, she refused to return his phone calls until one day, by mistake, she picked up the phone and there he was. Hel-lo, President Nixon

As Jackies condition worsened, the press grew more impatient for news. Jackies attitude to reporters had always been that they should be told as little as possible. As far back as the White House, her formula had been to give them minimum information with maximum politeness. Tuckerman knew that Jackie wouldnt want them to know that her illness was developing complications and becoming more serious, so her press bulletins remained opaque and featureless. This irritated the head of the hospital. He didnt want Jacqueline Onassis dying in his hospital to the surprise of the whole world. So he called Tuckerman in to upbraid her. Why, the hospital head asked her, was she telling the press that Jackie was doing as well as can be expected when she knew, in fact, that Jackie was dying?

Nancy Tuckerman defended herself as best she could. She was also under pressure from Jackies family to divulge as little as possible about her health. Caroline and John had had trouble getting through the front doors of the hospital because of the gathered reporters and photographers. The family didnt want to encourage more crowds or speculation. Tuckerman fell back on the only human defense she could think of before the big man across the desk from her: Shes my friend. And Im not going to say shes dying when I have not been told so.