Chapter One

Janie finished her essay.

She never knew what grade she would get in Mr. Brylowe's English class. Whenever she joked, he wanted the essay serious. Whenever she was serious, he had intended the essay to be light hearted.

It was October.

Outdoors throbbed with autumn. She could feel the pulse of the deep-blue skies. With every leaf wrenched off its twig and whirled by the wind, Janie felt a tug. She felt like driving for hours; taking any road at all; just going.

Actually Janie was only fifteen and had barely started driving lessons. She was having driving fantasies because of dinner last night.

Her parentsas alwayshad taken opposite sides. Setting themselves up like a debate team, her mother and father would argue until some invisible marital timer rang. Then they would come to terms, rushing to meet in the middle. Until last night her mother had said Janie could begin driv ing while her father said she could not. "She's just a baby," said her father, in the infuriating, affectionate way of fathers.

"She's old," said Janie's mother lightly. "Prac tically a woman. A sophomore in high school."

"I hate when that happens," her father grum bled. "I like my little girl to stay little. I'm against all this growing up." He wound some of Janie's hair around his wrist.

Janie had fabulous hair: a wild, chaotic mane of red curls glinting gold. People always commented on it. As her best friend, Sarah-Charlotte, said, " Janie, that is serious hair."

"I guess you've grown up anyway, Janie," said her father reluctantly. "Even with all the bricks I put on your head to keep you little. Okay, I give in. You can drive."

In English, Janie smiled to herself. Her father was an accountant who in the fall had time to coach the middle-school soccer teams. Today after school he'd have a practice, or a game, but when he came homethey'd go driving!

She wrote her name on her essay.

She had gradually changed her name. "Jane" was too dull. Last year she'd added a "y," becom ing Jayne, which had more personality and was sexier. To her last nameJohnsonshe'd added a "t," and later an "e" at the end, so now she was Jayne Johnstone .

Her best friendsSarah-Charlotte Sherwood and Adair O'Dellhad wonderful, tongue-twisting, memorable names. Why, with the last name John son (hardly a name at all; more like a page out of the phone book) had her parents chosen "Jane"? They could have named her Scarlett, or Allegra. Perhaps Roxanne.

Now she took the "h" out of Johnston and added a second "y" to Jayne.

Jayyne Jonstone . It looked like the name you would have if you designed sequined gowns for a living, or pointed to prizes on television quiz shows.

"Earth to Janie," said Mr. Brylowe.

She blushed, wondering how many times he had called her.

"The rest of us are reading our essays aloud, Janie," said Mr. Brylowe. "We'd like to issue an invitation for you to join us."

She blushed so hotly she had to put her hands over her cheeks.

"Don't do that," said Pete. "You're cute when your face matches your hair."

Immediately, the back row of boys went into barbershop singing, hands on hearts, invisible straw hats flung into the air. "Once in love with Janie," they sang.

Janie had never had a boyfriend. She was al ways asked to dances, was always with a crowdbut no boy had actually said I want to be with you and you alone.

Mr. Brylowe told Janie to read her essay aloud.

The blush faded. She felt white and sick. She hated standing up in class. Hated hearing her voice all alone in the quiet of the room.

The bell rang.

English was a split period: they had lunch in the middle and came back for more class. Never had lunch come at such an appropriate moment. Perhaps she would write a better essay during the twenty-seven minutes of lunch.

Certainly it wasn't going to take Janie long to eat. They had recently discovered she had a lac tose intolerance. This was a splashy way of saying she had stomachaches when she drank milk. "No more ice cream, no more milk" was the medical/ parental decree.

However, peanut butter sandwiches (which she had in her bag lunch) required milk. I am so sick of fruit juice, Janie thought. I want milk.

She had been eating since the school year be gan with Pete, Adair, Sarah-Charlotte, Jason, and Katrina.

She loved all their names.

Her last-year's daydream--before a driver's li cense absorbed all daydream timehad been about her own future family. She couldn't picture her husband-to-be, but she could see her children perfectly: two beautiful little girls, and she would name them Denim and Lace. She used to think about Denim and Lace all the time. Shopping at the mall with Sarah-Charlotte, she'd go into all the shoe stores to play with the little teeny sneak ers for newborns, and think of all the pretty clothes she'd buy one day for Denim and Lace.

Now she knew those names were nauseating, and if she did name her daughters Denim and Lace, there'd probably be a divorce, and her hus band would get custody on the grounds anybody who chose those names was unfit. She'd have to name them something sensible, like Emily and Margaret.

Peter, Adair, Sarah-Charlotte, Jason, Katrina, and Janie went in a mob down the wide stairs, through the wide halls, and into the far-too-small cafeteria. The kids complained about the archi tecture of the school (all that space dedicated to passing periods and hardly any to lunch), but they loved being crammed in, filching each oth er's potato chips, telling secrets they wanted ev erybody to overhear, passing notes to be snatched up by the boy you hoped would snatch them, and sending the people on the outside of the crush to get you a second milk.

Everybody but Janie Johnson got milk: card board cartons so small you needed at least three, but the lunch ladies would never let you. Janie was envious. Those luckies are swigging down nice thick white milk, she thought, and I'm stuck with cranberry juice.

"Okay," said Sarah-Charlotte. Sarah-Charlotte would not bother with you if you tried to abbrevi ate her name. Last year she had reached a stand off with a teacher who insisted on calling her Sarah. Sarah-Charlotte glared at him silently for months until he began calling her Miss Sherwood, which let them both win. "Okay, who's been kid napped this time?" said Sarah-Charlotte wearily, as if jaded with the vast number of kidnappings in the world. Sarah-Charlotte patted her white blond hair, which was as neat as if she had cut it out of a magazine and pasted it onto her head. Janie, whose mass of hair was never the same two minutes in a row, and whose face could be difficult to find beneath the red tangles, never figured out how Sarah-Charlotte kept her hair so neat. "I have approximately five hundred thou sand fewer hairs than you do," Sarah-Charlotte explained once.

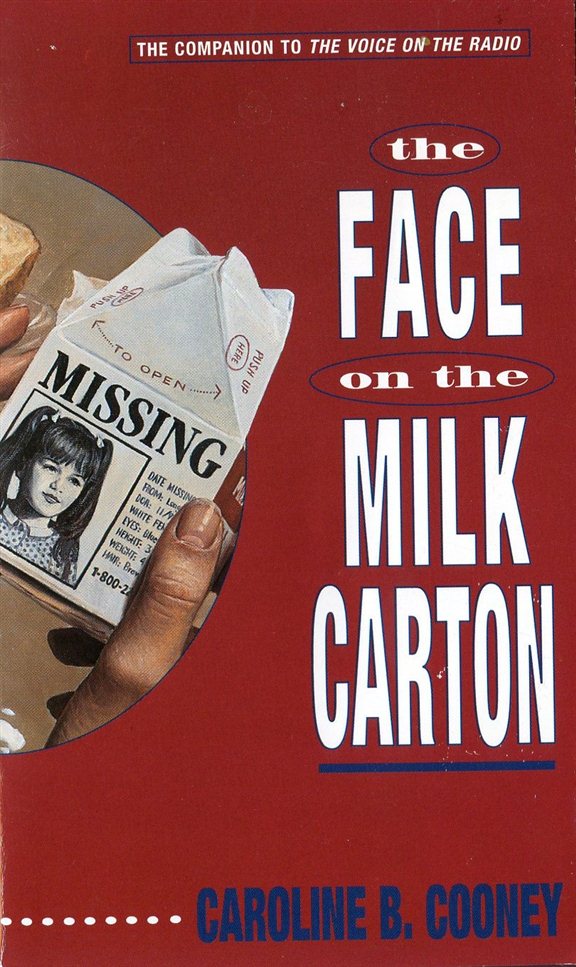

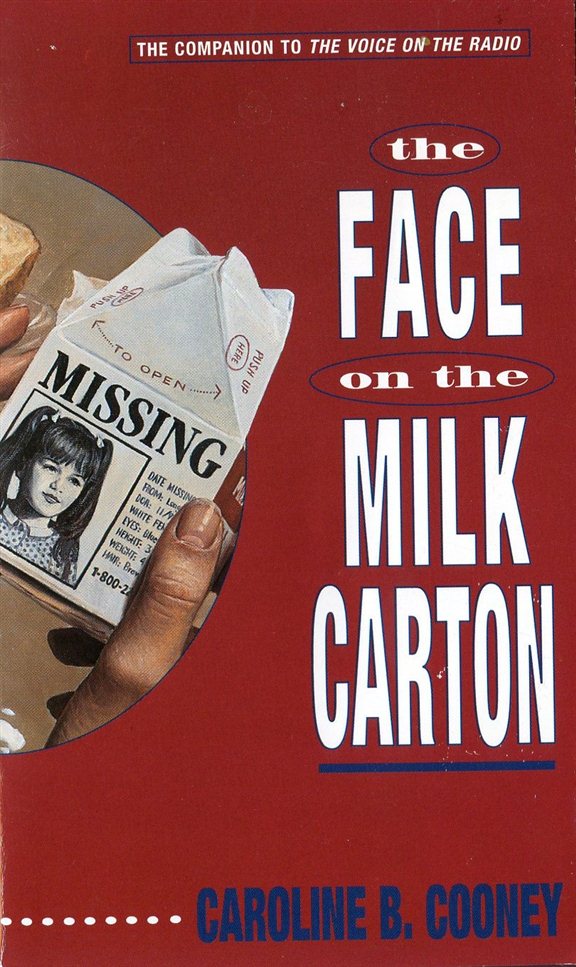

Everybody turned the milk cartons over to see who had been kidnapped. The local dairy put pic tures of stolen children on the back of the carton. Every few weeks there was a new child.

"I don't know how you're supposed to recog nize somebody who was three years old when she got taken from a shopping center in New Jersey, and that was nearly a dozen years ago," said Adair. "It's ridiculous." Adair was as sleek and smooth as her name; even her dark hair matched: unruf fled and gleaming like a seal out of water.

Janie sipped juice from a cardboard packet and pretended it was milk. Across the cafeteria Reeve waved. Reeve lived next door. He was a senior. Reeve never did homework. It was his life ambi tion to get in the Guinness Book of World Re cords, and the only thing he had a stab at was the "Never Did His Homework Once but Still Got the Occasional B Plus" listing.

Next page