For more than forty years,

Yearling has been the leading name

in classic and award winning literature

for young readers.

Yearling books feature children's

favorite authors and characters,

providing dynamic stories of adventure,

humor, history, mystery, and fantasy.

Trust Yearling paperbacks to entertain,

inspire, and promote the love of reading

in all children.

OTHER YEARLING BOOKS YOU WILL ENJOY

THE PENDERWICKS Jeanne Birdsall

BALLET SHOES, Noel Streatfeild

DANCING SHOES, Noel Streatfeild

THEATER SHOES, Noel Streatfeild

A SINGLE SHARD, Linda Sue Park

THE DIARY OF MELANIE MARTIN, Carol Western

MELANIE MARTIN GOES DUTCH, Carol Weston

SAMMY KEYES AND THE PSYCHO KITTY QUEEN

Wendelin Van Draanen

For Jonathan Shaw

Contents

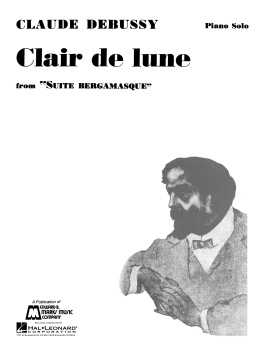

O nce upon a timeone hundred years ago, and half as many years againthere lived a girl called Clair-de-Lune, who could not speak.

She lived with her grandmother in an attic at the top of a very tall, very narrow, very old building, with six floors ahd twelve rickety flights of stairs climbing up and down precariously between them. They were very poor. But they were also very gentillies, which means that Clair-de-Lune's grandmother thought a good deal about table manners and ladylike behavior, and would rather starve than be considered ill-mannered. In winter, the attic was cold, and the wind blew through the cracks around the windowpanes, and snow floated in through the ceiling But in spring and summer, the sparrows and the swallows and the doves and the pigeons flew in flocks past the attic windows, and Clair-de-Lune would wake in the morning to the strange, lovely sound of their wings beating against their breasts.

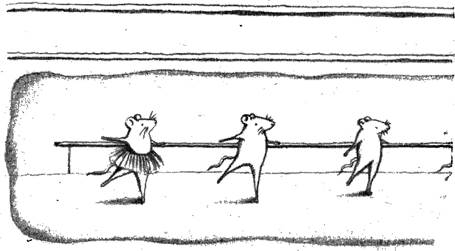

Clair-de-Lune's grandmother had jbeen a ballerina, and so had Clair-de-Lune's mother. So it will not surprise you when I say that Clair-de-Lune spent every morning, Monday to Saturday, in a large, long room three floors below with four and twenty other girls and boys and a strict ballet master by the name of Monsieur Dupoint, for she was learning to be a dancer, too. In the afternoons she studied geography and history and French and Italian and went to the market for her grandmother, who was very frail (although as slim and straight-backed as a young tree) and rarely moved from the attic. On Sundays, Clair-de-Lune went to church, where she opened her mouth in time with the music but did not sing.

Why was it that Clair-de-Lune could not speak? Ah! Nobody knew. But Clair-de-Lune's mother had died when she was a baby, and it was thought to have something to do with that.

Clair-de-Lune's motherwho had been known as La Lune, which means the moonhad been much celebrated for a famous pas seul that came at the end of a tragic and beautiful ballet about swans, who, it is said, are mute until the very last moments of their lives, when they give forth the loveliest of all songs. Many years before the first performance of Swan Lake, and many years more before Anna Pavlova conquered the world with The Dying Swan, La Lune danced the role of a swan mortally wounded by the crossbow of a hunter, in a long white tutu made of layers and layers of tulle and swans' feathers. And though La Lune made no sound, for dancers do not, there was one night when all the audience swore that she was singing the most unearthly song, as if her dancing was so beautiful that you could hear it. On that night, when she sank to the boards at the end of her pas seul, folding herself like a bird, she rested her head among the tulle and the feathers of her skirt, and did not rise again.

Brava! Braval came the shouts from the audience, whose clapping and cheering were like thunder. At first, no one understood that anything was wrong. It was some moments before the audience, at first uncertain, grew quiet; before the curtains were drawn hurriedly and a doctor called; before the audience began to whisper, then to murmur among themselves. Then came the announcement, with the head of the Company in tears: Ladies and gentlemen, La Lune is dead! The doctor says her heart was weaktoo weak for her to dance. If only we had known! and the sobs of the audience, and the flowers, which poured in from all over the country for weeks.

Some who were backstage on the night La Lune died said it was not singing they heard, but speechthat La Lune, the mute swan, the ballerina, had died trying to say something.

As for Clair-de-Lunewell, La Lune's public did not even know she existed. But she, too, was backstage that night, and though she was only a tiny baby, she must have understood something. For, from that day to this, she had never uttered a word.

Did Clair-de-Lune mind about not speaking? Ah, reader! It seemed to her that as each day passed, the weight of things unsaid grew heavier and heavier on her heart.

E very morning, come rain or sunshine-even in winter, when the snow lay on the groundClair-de-Lune would kneel on the window seat, push open the casement, lean her elbows on the windowsiU, and gaze out of the attic, trying to speak.

Sometimes, when the sun was shining, or even in the gentle rain, she would feel happy while she was doing this, because there was a kind of peace in looking out the window, a kind of privacy. Suddenly she was alone with the view, and the view almost seemed to look back at her, liking her, and not minding that she was mute.

But most often she was sad, because she longed to be able to speak, and yet, no matter how much she longed, no matter how hard she tried, no words came. She would sit gazing out at the acres and acres of brownish red rooftops, for that was all that could be seen from the attic windowbrownish red slate roofs, sloping unevenly; drainpipes; a steeple in the distance; a black cat picking its way over the roof opposite; chimneys; pigeons; sparrows; swallows; doves; and on sunny days a small blue square, which was the sky. And as she gazed, she would be overwhelmed by longing, until the tears pricked at her eyes and overflowed and the red roofs swam together.

And then her grandmother would call to her to hurry up and finish dressing, for she must be at her class by nine o'clock, and she would pull in her head and obey.

To class every morning, Clair-de-Lune wore rose-pink stockings and practice shoes and a sharply waisted white muslin practice dress with matching pantalettes, which extended threeinches below the hem of her calf-length skirt. A black sash went around her waist. The dress was dcollete that is, it left her throat and shoulders bareand, like all the other girls, she parted her hair in the middle and smoothed it back modestly into a chignon that rested on the nape of her neck. A black snood kept her hair in check. The whole ensemble was a compromise between modesty and the very real practical need to see as much as possible of what the limbs and body were doing during a ballet class. Modesty had prevailed, however. Clair-de-Lune was learning to dance en