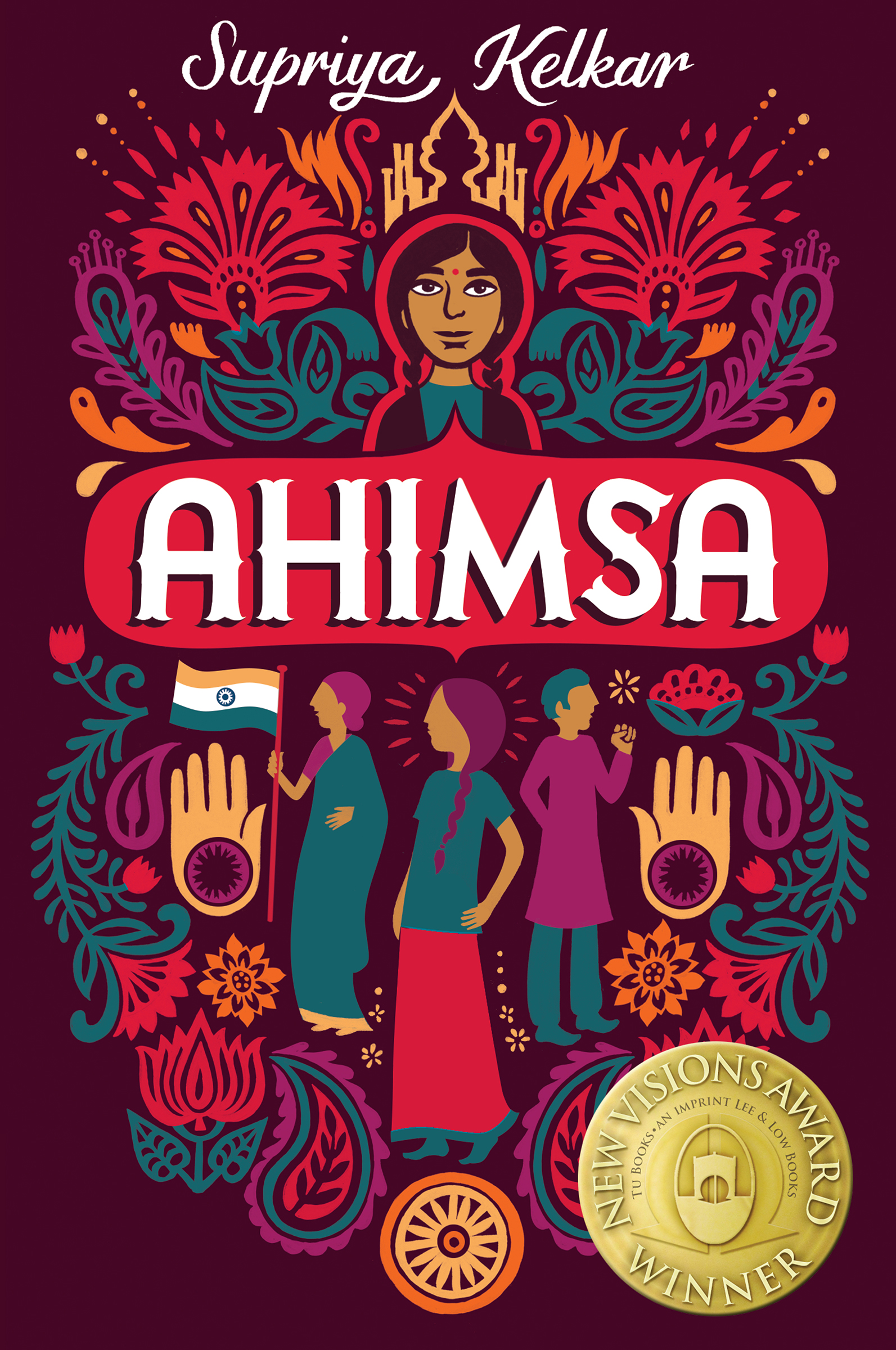

Praise for

Young Anjalis journey of awakening opens windows upon the complex history of Indias independence struggle. With simple text and dramatic action, we are drawn into one girls life and the steps she must take in her swiftly changing world. Here is a compelling character impetuous, intelligent, and brimming with heart. At the same time, Kelkars novel reveals the power of compassion, as Anjali grows to be a clear-eyed witness to her time and a hero for our own.

Uma Krishnaswami, author of Book Uncle and Me and Step Up to the Plate, Maria Singh

As the world around us is getting more divided, Supriya Kelkar has written a simple and yet compelling story about love and tolerance. Both her protagonists are strong women who take the lead in changing the world, even though one of them is only ten. Read out Ahimsa to your children. Its an important lesson delivered through a delightful story.

Vidhu Vinod Chopra, director of the films 1942: A Love Story and Eklavya: The Royal Guard

An eye-opening tale of dramatic events and richly diverse characters who discover that, with time, determination, and ahimsa, young people can solve real problems in the world.

Cynthia Levinson, author of T he Youngest Marcher and Weve Got a Job

Sprinkled with action as this story is, it is also packed with a wealth of interesting information and teachers and librarians will find much in this book to spur thoughtful discussions. Readers are also sure to discover parallels between the desegregation of schools in our nation and the attempt to integrate lower-caste children into the Indian education system.... A welcome addition to the growing body of South Asian literature for children in the United States.

Padma Venkatraman, author of Climbing the Stairs and A Time to Dance

Kelkar gives us a front row seat at a critical moment in history with skill and emotion as we journey through India with Anjali, a feisty, inquisitive daughter of a freedom fighter who strives to stay true to Gandhis philosophy of nonviolence, ahimsa, while tackling issues of colonialism, caste, womens rights and communal violence at the eve of the countrys independence.

N. H. Senzai, author of T icket to India

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright 2017 by Supriya Kelkar

Jacket illustration copyright 2017 by Kate Forrester

Translation on page 56 of Jhansi Ki Rani by Subhadra Kumari Chauhan 2017 Subhash Kelkar.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

TU BOOKS, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS Inc., 95 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

leeandlow.com

eISBN 9781620143575 (version 2.0)

Book design by Neil Swaab

Book production by The Kids at Our House

First Edition

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress

To my parents

T hey wouldnt hang a ten-year-old girl, thought Anjali, clenching a small tin of black paint. She took care not to get any on the skirt of her saffron ghagra-choli woven with real gold thread. It was Anjalis Diwali present from last year, made from the most expensive fabric in the shop. She had picked it out herself. And she had managed to keep it as bright and crisp as the day she had gotten it, despite heavy monsoon rains that had drenched her little town in the middle of India.

Hurry up, whispered her friend, Irfaan, as he glanced nervously around them. Perspiration beaded around his collar near the black thread of his taweez, the necklace whose locket contained Koran verses. Clad in a cool white pajama-kurta, he was more appropriately dressed for the muggy August weather than Anjali, but he couldnt stop sweating. We cant get caught.

Getting caught vandalizing someones property would lead to quite the punishment under normal circumstances, but Anjali was about to do far worse. She was about to vandalize a British officers property. A British officer who was in charge of making sure the British Rajs orders were carried out in their town. A British officer who happened to be the former boss of Anjalis mother.

Only a week earlier, Anjali had stopped by the captains office after school to catch a glimpse of her mother through the window, as she had often done for the past year since her mother became one of Captain Brents secretaries. Anjali normally found her mother translating decrees and legal notices for Captain Brent, typing letter after letter on his behalf to their fellow townspeople, rejecting requests from families begging for mercy for their imprisoned freedom-fighter sons.

That day had looked like any other. She had found her mother hunched over the corner room desk, typing away, as Captain Brent lounged on his scarlet silk sofa under a faded oil painting of Queen Victoria. He was dictating to Anjalis mother in his harsh foreign accent, and Anjali couldnt help but stare.

The next day, her mother was out of a job.

Anjali still didnt know what had happened, only that her mother and father had fought, and that her great-uncle, Chachaji, who lived with her family, had never approved of her mothers job in the first place.

Anjalis mother had just become one of Captain Brents secretaries when Chachaji moved in with them after a close call in one of the Hindu-Muslim communal riots that swept the city of Bombay in 1941. Chachaji was old and old-fashioned, and couldnt get past the fact that a woman was working outside the house.

But Anjalis father didnt mind that Ma worked. The extra money came in handy for feeding the extra mouth. And Anjalis mother was college educated, so why shouldnt she put her proficiency in typing and her fluency in English and five native Indian languages to use?

Anjalis mother hadnt mentioned Captain Brent all week, except to say she was relieved she didnt have to see him anymore. But there was something Ma wasnt saying. Had Captain Brent not paid her? Or had he hurt her? Anjali only knew one way to handle the situation: to hurt the captain back.

So when Irfaan got a half-empty container of paint from his fathers newly painted dairy and asked Anjali what they should paint, she knew just how shed do it. She and Irfaan would paint Q short for Quit India on the bungalow he worked out of. Maybe then Captain Brent and the other British officers would finally leave India for good.

Over the past few weeks, it seemed like all the British officers houses and workplaces but Captain Brents had been vandalized with a Q. He was definitely one of the more intimidating British officers, ordering everyone around regardless of their caste, acting like all Indians were Untouchable.