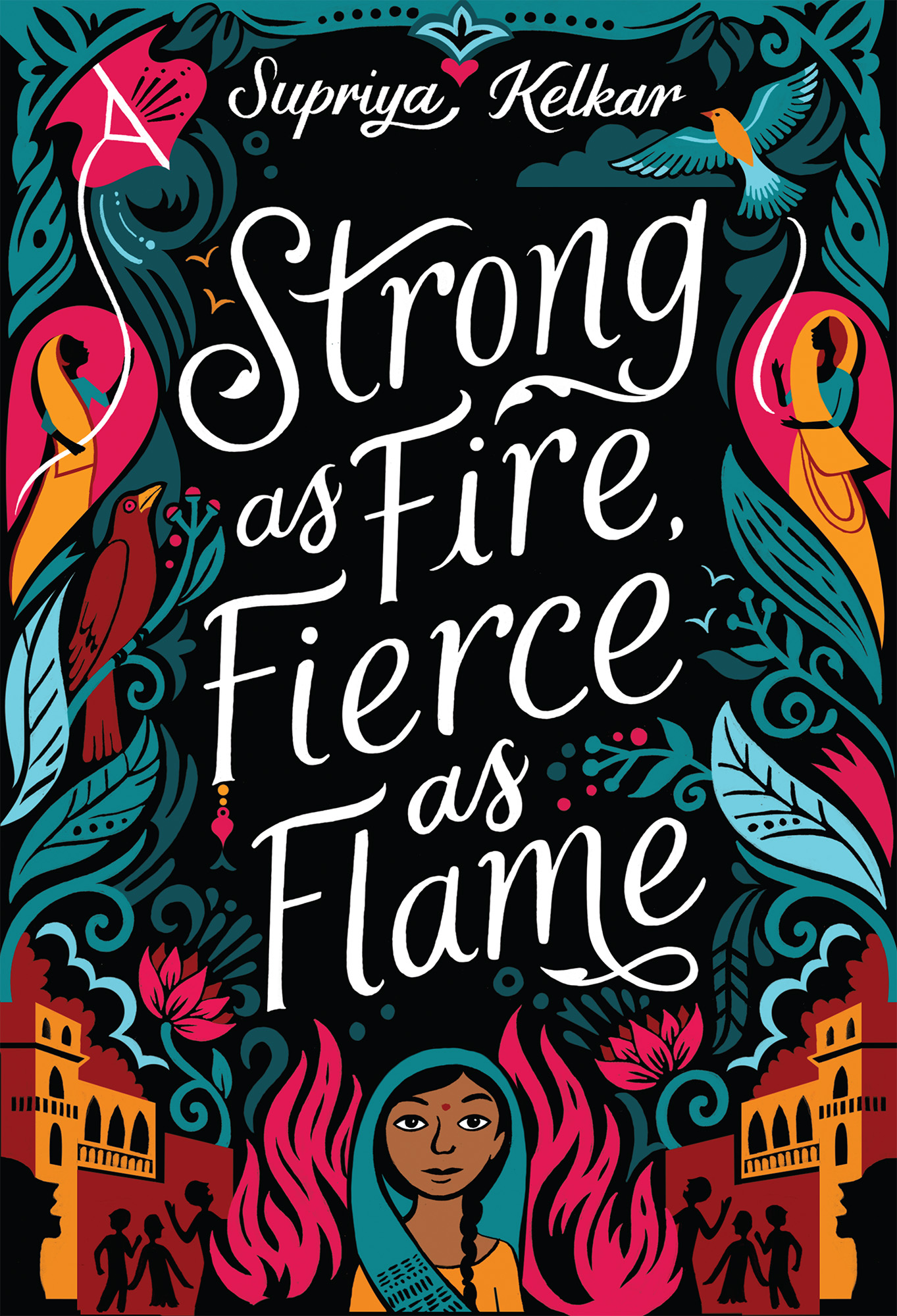

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

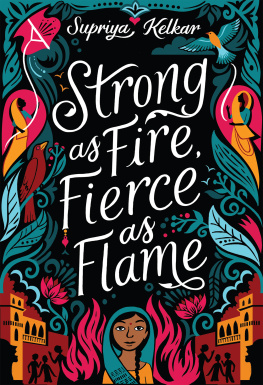

Copyright 2021 by Supriya Kelkar

Jacket illustration by Kate Forrester

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

TU BOOKS, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS Inc.,

95 Madison Avenue,

New York, NY 10016

leeandlow.com

Edited by Stacy Whitman

Book design by Sheila Smallwood

Interior illustrations by Kate Forrester

Map art by Vikki Zhang

First Edition

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress

To Aaji, Bhausaheb, Bapu, Vahini, Anand Ajoba, and Nalu Aaji

Chapter 1

M y father taught the village boys right outside our little earthen home, but I wasnt a boy, so I didnt get to learn. That didnt stop me from trying, though. I sat high up in the tree at the end of our front yard, peering through the rubbery green leaves as my father started the school day like he always did: by writing the date on the black writing slate in his hand.

The boys, sitting cross-legged on the ground, copied the date on their slates. Although I couldnt read what was written, I knew what the day was before Babuji said it. Because in three days it was my thirteenth birthday, and my mother had been talking about it for weeks.

Meera! Ma called out to me as she rushed from the doorway of our tiny rectangular home, a wicker bowl in her hand. The handful of distracted village boys turned her way, and Babuji gave her a sharp look for disturbing his class. Ma quickly grabbed the pleats of her dusty indigo sari as she hurried apologetically past my father toward me.

Meera, she whispered, swatting at my dangling left foot until I was forced to jump down, you know you arent allowed in his class. We have to get to the market. The vermilion bindi crumpled in the sudden wrinkles between her eyebrows. We only have three more days.

Ma bit her lip like she always did when she was sad and began down the village path, guiding me along. We passed house after house still glistening with dewdrops from the night before, bleating goats, and a prowling orange-and-white cat, its fur matted with dirt. And Ma kept chewing at her lower lip. She wasnt sad because I was turning thirteen in three days. She was sad because in three days, I was going to have to move in with my husband and his family. I was sad too. And frustrated that I didnt have a say in any of this. After all, it was my life, my future, that was being determined for me.

Krishna and I were married when we were little. Ma loved to tell the story, far out of Babujis earshot, of what happened when I saw the sacred fire that we would circle in the ceremony. I got so nervous at seeing the flames up close, at feeling the heat against my tiny sari, Id had an accident. In Babujis lap. I bet not many brides wet themselves on their wedding day. But what did you expect from a scared four-year-old?

Youll remember to behave yourself there, wont you, Meera? Ma asked as we walked past the large round stepwell you could gather water from or swim inside. We turned toward the tiny gray stone temple that peacocks pranced around. I gazed at the birds, at the brilliantly colored male who got all the attention from passersby for his stunning display of feathers while the peahens seemed to do all the work, caring for their young in the background.

And youll listen, right? You wont stare off at the birds when Krishnas mother tells you to do something?

Taking in the winking golden eyes on the peacocks feathers, I shook my head. No birds. Ill do whatever she says, I replied like the obedient daughter I was supposed to be, despite how unfair I thought it all was.

Ma held me tighter as we passed a couple women sitting on the ground outside the temple, dressed in white cotton saris with shaved heads and hands out. They sang songs to beg for money. They were widows who often came from tiny homes with large households that had too many mouths to feed. Sometimes, when they became a burden, some widows would be forced out of their homes. With nowhere to go, they often begged at our temple, wearing white because they werent allowed to wear colors after their husbands died.

I scrunched the fabric of my orange-and-maroon sari as I looked at one of them. Her eyes were cloudy gray with age, her wrinkles set deep in sadness. It must not have felt nice to be kicked out of your house or not get to wear colors anymore, and maybe some felt jealous of the thousands of widows whose families didnt abandon them, whose children lovingly took care of them until they died of old age.

But being an abandoned widow sure seemed better than the other alternative: sati. Sati was a rare, ancient tradition that only a few families practiced, in which some widows, who didnt have young children to care for, sacrificed themselves on their husbands funeral pyre to join them in the afterlife.

At the sight of the widows, a desperate flutter began in my belly. I hastened down the lane past them with Ma. The widows songs soon faded to a faint whisper in the wind as we neared the market, full of stalls of fruits and vegetables, clay and metal vessels, and grains, all shaded by canopies of orange, red, and yellow fabrics on either side of the small, well-worn path. The voices of villagers bargaining and merchants announcing what they were selling filled the air as we entered the crowded bazaar.

I polished the bangles today, Ma said, examining some grains of millet in a basket at a stall.

Again? Youve been cleaning them every day, I replied, fanning my face for a little break from the humid air.

Its your dowry. I want it to be perfect. Ma moved to the next stall.

I nodded, following her. My dowry was the amount promised to Krishnas family for taking care of me when we got married. It was tradition, and my parents were giving away much of what they had in those two gold bangles that made up my dowry. I ran my fingers over some clay pots, thinking about how, thanks to dowries, some girls like me were a burden for their poor families, just like those temple widows were burdens for their families after they were married.

Ma stopped to purchase a tiny cup and handed it to me. Take it with you to your new home and think of me every time you drink your water.

That sad quiver started in my gut again as I squeezed the cup against my chest, shadowing Ma farther into the market down the twisting lane cramped with people.

We dashed past a handful of men puffing on their beedis, holding our breath as they exhaled the sickening smoke, and turned past the house of the jaggery merchant. A dozen people were gathered outside it, laughing and clapping as they sang a folk song. Right in front of the house, an old lady dressed in a gold-and-white sari sat on one side of a large set of scales, her face flushed from a mixture of embarrassment and laughter. On the other, the family members and friends waiting by the house placed block after block of golden jaggery, made from sugar cane juice, until the old ladys side of the scales rose up in the air, finally weighing the same as the sweet jaggery bricks on the other side. The old lady smiled a wide, toothless grin as the revelers hooted in celebration.

Next page