To my sons, Ghamr and Taim, and their peers. J.S.

To my sons, Sam and Joe. S.E.M.

There is hope after despair and

many suns after darkness.

Rumi

THE END

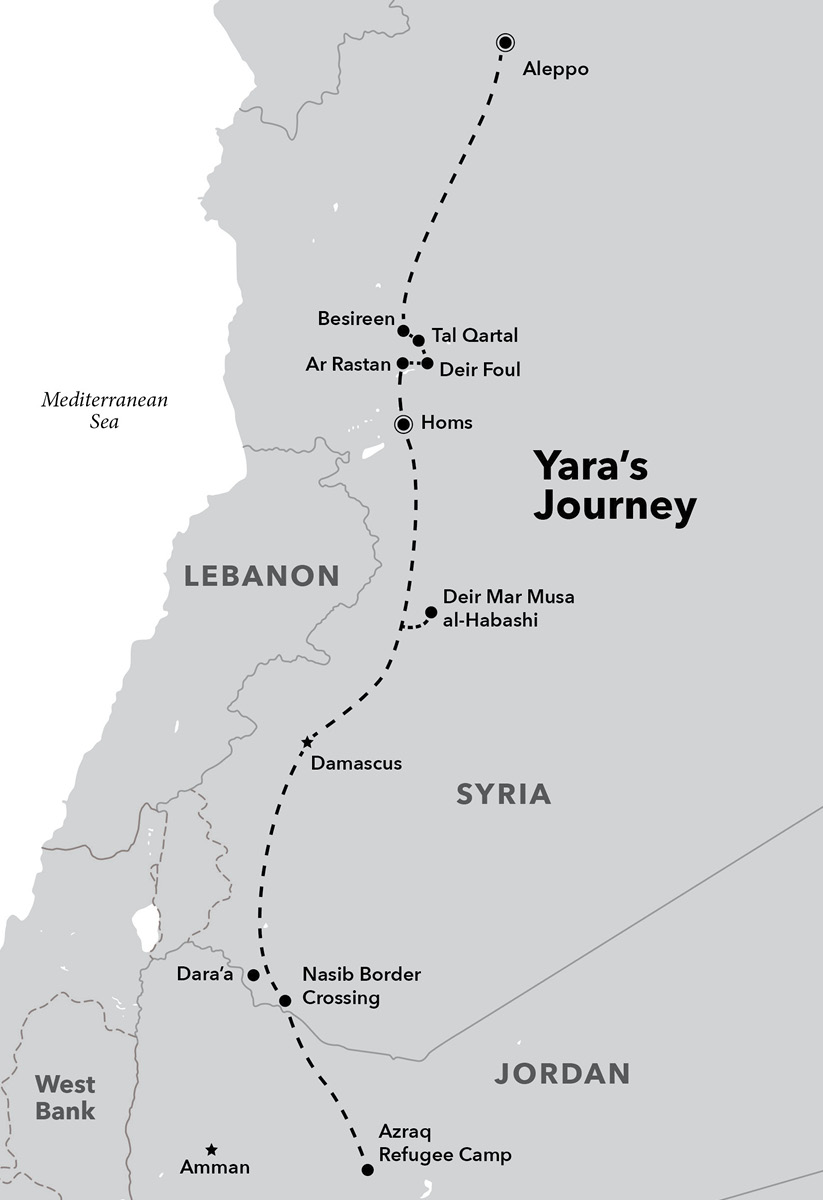

Azraq Refugee Camp, Jordan

2016

T he morning sun was a thin, orange strip on the horizon. Spinning golden sand blurred the rows and rows of the camps rectangular tin shelters. Around Yara, women charged the wind, their eyes blinking under sand-encrusted scarves, their long black gowns slapping against their ankles like the beating wings of crows.

She felt the scribbled note in the pocket of her jeans. It read:

Stop by the office tomorrow. Mr. Matthew wants to see you.

Lina

The note had been delivered to her shelter last night. She hadnt slept since. What did he want? Had her application to go to a foreign country been rejected? Had they discovered that she had lied? That she had killed a man?

The rules are clear: if a lie is discovered on your immigration application, it will be terminated immediately, Mr. Matthew had said.

Yara moved through the camp, a long-limbed, sixteen-year-old girl who walked with purpose. From afar, she had the body of a long-distance runner. Up close she looked like a girl who had been half-starved for a long, long time.

It wasnt Yaras beauty that made her unforgettable. Her arched eyebrows and razor-sharp cheekbones were intimidating. Her brown eyes shot through with bolts of gold gave her the look of a tiger. She held her head high on thin shoulders that were as straight as arrows. But the set of her mouth, her clenched jaw, and a chewed lower lip told the real story. She had seen things, done things. She might have looked sixteen but inside she was old. Fifty? A hundred? How, in a war, could it be otherwise?

The office was ahead. It was a long, temporary shelter made of tin. Squinting, she could make out the blue letters UN on the office door, and beneath the letters, the name:

Matthew McGonagall

Counselor

Yara climbed three shaky wooden steps and knocked. Marhaba! she called out, offering hello in Arabic. She pressed her ear to the door. Marhaba, Lina! Lina was Mr. Matthews Jordanian assistant. She was kind and soft-spoken, with dark eyes rimmed in charcoal-black. She was not much older than Yara, maybe eighteen or nineteen?

Hello? Mr. Matthew, hello! Yara tried English this time and again hammered the door. Still nothing. But Mr. Matthew often worked in the early morning, before the heat of the day set in. He used to call himself Matt, but his Jordanian co-workers had laughed. Matt in Arabic meant died.

And his last name was unpronounceable. Mick-gooo-naa? No. Mack-gone-gal? They had agreed that Mr. Matthew would do.

He was from Canada. Or maybe Scotland. But the Scots talked differently, didnt they? He had red hair that lit up his head like he was on fire. His eyes were pale blue, like water. And he was bignot fat, but when he stood up from his desk it seemed as if the tin walls of his office might burst apart.

Hello? Yara called out again. Still nothing. Damn, she mumbled. It was her favorite English word. She gave up and thumped back down the steps. If she returned to her shelter she would be put to work changing, washing, and feeding babies. And she was so tired.

There was only one place she could hide and wait for Mr. Matthew or Lina to open the office.

Head bowed, Yara covered her mouth with the end of her headscarf and trudged on.

The hospital with the new maternity wing was to her right; the community hall was to her left, and there was a basketball court beside it. The main gate was ahead. Even this early there were boys clustered around the gate like bees. Likely they had not been to bed. This was the place where recruiters for ISIS, al-Nusra, and other gangs chanted into young boys ears: Make your life worthy of Allah and join us in the fight against the infidels.

The United Nations guards chased the recruiters away, but they came back and back and backwaves of black-toothed, evil men with sneers on their lips and dull, empty eyes.

This was also the place where rich men from other countries came to buy girls. They wanted wives, or so they said. Yara pursed her lips so tight they went white. She knew the English words for it: human trafficking. She knew better words: tijarato ar-raqeeq, slave trading.

They were told that they were safe in the camp but only if they were not stupid, another good English word.

A boy spotted her. Where are you going? he called out. Come and talk with us. We can make you rich.

Yara hunched her shoulders and pulled her headscarf down over her forehead. She wished the UN guards would chase the boys away, too. But where would they go? Back to crowded shelters that stank of dirty diapers.

Hey, sharmouta! The boys came closer.

Yara spun around, fists clenched. There were three of them. How old were they? Ten? Eleven? In the early light she could make out their shapes but not their features. They stood with their feet rooted like trees.

Sharmouta! Sharmouta! Sharmouta! they chanted. Prostitute? Were they calling her a prostitute? Did they think she would take their dirty talk?

You are old. You need a husband, one yelled again while the other two laughed. We can get you a husband, the second boy shouted. Rage surged through her as fast and hot as a bullet. Fifty American dollarsthat is what we can get for you. Maybe a hundred! All three boys stomped about and cheered.

On the ground in front of her was a round gray rock. It fit perfectly into the palm of her hand. As her arm crested into an arc above her head, the rock sailed gracefully up into the air and disappeared into the grainy mist. Thud. A scream. Her eyebrows arched and her mouth twitched into a smile. She had hit her mark.

Come and get me, dirty donkeys, she growled through clenched teeth. One boy was making mewing sounds, likely the one who got hit. Good. The others had stopped dead in their tracks.

YOU ARE DONKEYS! she yelled. She had called them idiots. They reared back like pack animals.

A man, likely a guard, called out, Whats going on?

Yara waited. She heard the stupid boys retreating footsteps. Cowards, she muttered. COWARDS! she shrieked.

The guard called out something else. His voice was only an echo now. He was following the boys.

The tip of her shoe stubbed against another rock. The donkeys might return. She crouched. Her fingers curled around another lucky find. It was a hunk of concrete. It would do.

The wind blew stronger and faster. Nearly blind from the sand, Yara stumbled into the school area that was tucked behind the basketball court. Nine tin shelters used as classrooms were boxed in a large square play space. There was a nook, a small opening between two buildings that shielded her from the wind and prying eyes. It was a good place to hide. Privacy was a precious thing in the camp.