I thank my steadfast editorial sisterhood once again:

Jennifer Rudolph Walsh, Beverly Horowitz, and

Wendy Loggia.

I thank my outstanding colleagues and friends at

Random House Children's Books: Chip Gibson,

Joan DeJMayo, Marci Senders, Isabel Warren-Lynch,

Noreen Marchisi, Judith Haut, John Adamo,

Rachel Feld, and Tim Terhune.

As ever, I lovingly acknowledge my husband,

Jacob Collins, my children, Sam, Nate, and

Susannah, and my parents, Jane and Bill Brashares.

T HE SMALLEST SPROUT SHOWS

THERE IS REALLY NO DEATH .

WALT WHITMAN,

SONG OF MYSELF

T he last day of school was a half day. Tomorrow the entire eighth grade would pile back into the gym for the graduation ceremony, but that was just for an hour and their families would be there. The next time Ama went to school, it would be high school.

Everything is changing, Ama thought.

Usually she took the bus home, but today she felt like -walking, she wasn't sure why. She wasn't sentimental. She was purposeful and forward- looking, like her older sister. But it was an aimless time of day, and she wasn't hauling her usual twenty pounds of textbooks, binders, and notebooks. Today she felt like treading the familiar steps she'd walked so many times when she was younger, -when she was never in a hurry.

She couldn't help thinking about Polly and Jo as she walked, so when she saw them up ahead, waiting at the light to cross East- West Highway, it almost felt like they appeared out of her memory.

Ama was surprised to see Polly and Jo together. From this long view, she was struck by the naturalness of the way they stood together and at the same time, the strain. She doubted they had started off from school together. These days Jo usually left school with her noisy and flirting group of friends to go to the Tastee Diner or to the bagel place around the corner. Polly went her own way taking forever to pack up her stuff and often spending time at the library before heading home. Ama sometimes saw Polly at the library and they sat together out of habit. But unlike Ama, Polly wasn't there to do her homework. Polly read everything in the library except what was assigned.

As Ama got closer, she considered how little Jo looked like she used to in elementary school. Her braces were off, her glasses were gone, and she devotedly wore whatever the current marker for popularity wasat the moment, pastel plaid shorts and her hair in two braids. Ama considered how much Polly, in her long frayed shorts and her dark newsboy cap, looked the same as she always had.

Ama! Hey! Polly saw her first. She was waving excitedly. The walk sign illuminated and Ama hurried to catch up to them so they could cross the highway together.

I can't believe you're here, Polly said, looking from Ama to Jo. This is historic.

It's on her -way home, Jo pointed out, not seeming to want to acknowledge the significance of the three of them -walking home together on this day.

Ama understood how Jo felt. The history of their friendship -was like a brimming and moody pond under a smooth surface of ice, and she didn't want to crack it.

As they walked they talked about final exams and graduation plans. Nobody said anything as they passed the 7-Eleven or even as they approached the old turn.

What if we turned? Ama suddenly -wondered. What if they ran down the old hill, past the playground, and stepped into the -woods to see the little trees they had planted so long ago? What if they held hands and ran as fast as they could?

But the three of them passed the old turn, heads and eyes forward. Only Polly seemed to glance back for a moment.

Anyway, even if they did turn, Ama knew it -wouldn't be the same. The creaky metal merry- go- round -would be rusted, the swing set abandoned. The trees might not even be there anymore. It had been so long since they'd tended to them.

Ama pictured her younger self, running down the hill -with her two best friends, out of control and exhilarated.

It was different now. People changed and places changed. They were going into high school. This was no time for looking back. Ama couldn't even picture the trees. She couldn't remember the name of the hill anymore.

When I think of the first day of our friendship, I think of the three of us running across East- West Highway with our backpacks on our backs and our potted plants in our hands. I think of Jo dropping her plant in the middle of the street and all of us stopping short, and the sight of the little s'talk turned on its side and the roots showing and the soil spilling onto the asphalt. I remember the three of us stooping down to put the plant back into its pot, hurriedly tucking its roots back under the dirt as the walk signal turned from white WALK to blinking orange DON'T WALK. And I remember Ama shouting that we had to hurry, and seeing, over my shoulder, the cars pouring over the hill toward us. I remember the rough feeling of the asphalt scraping under my fingers as I swept up the last of the dirt, the stinging feeling of my knuckles as I tried to gather it in my fist. I think it was Jo who grabbed my arm and pulled me to the sidewalk. And I remember the long, flat swell of the horns in my ears.

We met on the first day of third grade, because of all the 132 kids in our grade, we were the three who didn't get picked up. I was spooked, because my mom had never failed to pick me up from school. She'd never even been late before.

We didn't talk to each other at first. I was embarrassed and scared and I didn't want to show it. They put us in the math help room with the see- through walls. We stared out like a zoo exhibit waiting for our parents to come.

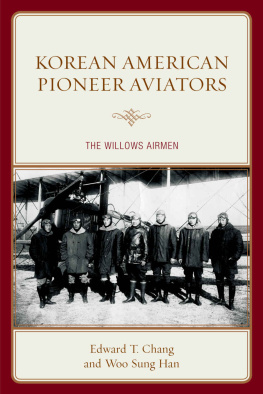

That was the day they gave out the little willow tree cuttings in plastic pots in our science class. We were supposed to take care of them and study them all year. I remember each of us sitting at a desk with our plant in front of us. Polly kept poking at hers to see if the soil was too dry. She hummed.