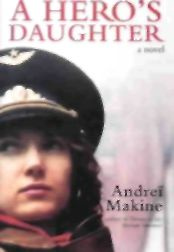

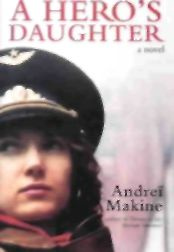

Andrei Makine

A Hero's Daughter

Translated from the French by Geoffrey Strachan

Andrei' Makine was born and brought up in Russia, but A Hero's Daughter, his first novel to be published, was, like his subsequent novels, written in French. The book is set in Russia, and the author includes a number of Russian words in the French text, most of which, with his agreement, I have kept in this English translation. These include shapka (a fur hat or cap, often with ear flaps); dacha (a country house or cottage, typically used as a second or vacation home); izba (a traditional wooden house built of logs).

The text contains a number of references to events and institutions from the years of the Second World War, 1941 to 1945; the polizei was a force of Russian collaborators recruited by the occupying German power to assist them; the Panfilova Division (the 316th Rifle Division led by Major General Ivan Panfilov) became celebrated for the heroism of twenty-eight of its soldiers, who threw themselves with their grenades in the path of advancing German tanks in the defense of Moscow during the winter of 1941 and prevented them from breaking through.

There are also a number of references to institutions and personalities from the Communist era in Russia. A soviet was an elected local or national council as well as the building it occupied in a town or village. The NKVD (Narodny Kommissariat Vnutrenikh Del), the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs, were the police charged with maintaining political control during the years of Stalin's purges from 1934 to 1946. The KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoi Bezopasnosti), the Committee of State Security, was created in 1953, on Stalin's death, to take over state security with responsibility for external espionage, internal counterintelligence and internal "crimes against the state"; its most famous chairman was Yuri Andropov. A kolkhoz was a collective farm, a kolkhoznik a member of the farm collective; a kulak was the derogatory term for a wealthy peasant, considered to be an enemy of the Soviet regime under Stalin. The Komsomol was the Communist youth organization, the junior branch being the pioneers. "Iron Felix" was Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the "Cheka," the forerunner of the NKVD; COMECON, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, was an economic association of East 'European countries during the Soviet era. "Beriozka" stores were created exclusively to sell goods to foreign visitors, who paid not in rubles but in foreign currency; some of these accepted vouchers from Soviet citizens who worked abroad and could exchange foreign currency for vouchers. Marshal Georgi Konstantinovich Zhukov was army chief of staff from 1941 onward; Geidar Ali Rza Ogly Aliev was a KGB general. A kommunalka was a communal apartment. The terms perestroka (reconstruction, reorganization) and glasnost (openness) became watchwords during the period of Mikhail Gorbachev's liberalization of the Soviet regime from 1985 onward.

G. S.

HOW FRAGILE AND STRANGE EVERYTHING IS down here

on earth

What his life had depended on was a fragment of tarnished mirror held in the fingers, blue with cold, of a medical orderly, slim as a young girl.

For there he lay, in this vernal meadow churned up by tanks, amid hundreds of greatcoats, all solidified during the night into an icy mass. The jagged ends of shattered beams bristled upward from a dark crater to the left of them. Close at hand, its wheels sunk into a half collapsed trench, an antitank gun pointed up at the sky.

Before the war, from reading in books, he used to picture battlefields quite differently: soldiers carefully lined up on the fresh grass, as if, before dying, they had all had time to adopt a particular significant posture, one suggested by death. In this way each corpse would be perceived in the isolation of its own unique encounter with mortality. And each of their faces could be studied, this one with his eyes uplifted toward the clouds, as they drifted slowly away, that one pressing his cheek against the black earth.

Which is why, when he was first skirting that meadow covered with dead, he had noticed nothing. He walked along, painfully heaving his boots out of the ruts on the autumn road, his gaze fixed on the back of the man in front of him, the faded gray greatcoat on which droplets of mist glistened.

Just as they were emerging from a village skeletons of half-burned izbas - a voice in the ranks behind him called out: "Holy shit! They sure had it in for the people!"

Then he took a look at the meadow that stretched away toward a nearby copse. He saw the muddy grass piled high with gray greatcoats, Russians and Germans, lying there at random, sometimes bundled together, sometimes isolated, face down against the earth. Then something no longer recognizable as a human body, a kind of brownish porridge, clothed in shreds of damp fabric.

And now he was one of these dead lumps himself. Stretched out there. Trapped in a little puddle of frozen blood beneath his neck, his head lay at an angle with his body that was inconceivable for a living being. His elbows were so violently tensed under his back that he looked as if he were trying to wrench himself up from the ground. The sun was only just glinting on the frost-covered scrub. In the forest, where it bordered on the open land and in the shell craters, the violet shadow of the cold could still be observed.

There were four medical orderlies: three women and a man who was the driver for the field ambulance into which they loaded the wounded.

The front was receding toward the west. The morning was unbelievably still. In the frozen, sunlit air their voices rang out clear and remote. "We must finish before it thaws out, otherwise we'll be up to our knees!" All four of them were dropping with weariness. Their eyes, red from sleepless nights, blinked in the low sun. But they worked effectively and as a team. They treated the wounded, loaded them onto stretchers, and slowly made their way to the van, crunching the lacework of ice, turning over the dead and stumbling in the ruts. The third year of the war was slipping by. And this springtime meadow covered in frozen greatcoats lay somewhere in the torn heart of Russia.

Passing close by the soldier, the young orderly hardly paused. She glanced at the puddle of frozen blood, the glassy eyes and the eyelids distended by an explosion and muddied with earth. Dead. With a wound like that no one could survive. She continued on her way, then went back. Averting her gaze from those horrible bulging eyes, she took out his service record.

"Hey, Manya," she called out to her comrade, who was tending a wounded man ten paces away from her, "he's a Hero of the Soviet Union!"

"Wounded?" asked the other one.

"Afraid not dead."

She bent over him and began breaking the ice around his hair so as to lift up his head.

"Well, then! Come on, Tatyana. Let's carry mine."

And Manya was already slipping her hands under the armpits of her wounded man, whose head was white with bandages.

But Tatyana, her hands moist and numb, hastily sought out a little fragment of mirror in her pocket, wiped it with a scrap of bandage and held it to the soldier's lips.

In this fragment the blue of the sky appeared. A bush miraculously intact and covered in crystals. A sparkling spring morning. The glittering quartz of the hoarfrost, the brittle ice, the resonant, sunlit void of the air.

Suddenly the whole icy scene softened, grew warmer, became veiled with a little film of mist. Tatyana jumped to her feet, holding the fragment aloft, as the light cloud of breath rapidly faded, and called out: "Manya, he's breathing!"

Next page