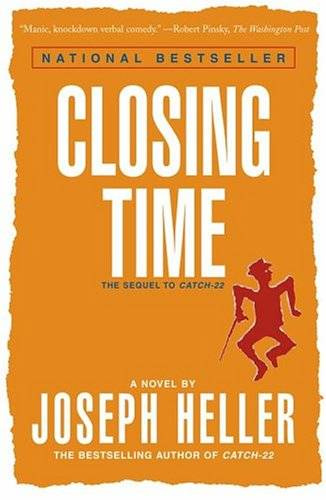

Joseph Heller

Closing Time

When people our age speak of the war it is not of Vietnam but of the one that broke out more than half a century ago and swept in almost all the world. It was raging more than two years before we even got into it. More than twenty million Russians, they say, had perished by the time we invaded at Normandy. The tide had already been turned at Stalingrad before we set foot on the Continent, and the Battle of Britain had already been won. Yet a million Americans were casualties of battle before it was over-three hundred thousand of us were killed in combat. Some twenty-three hundred alone died at Pearl Harbor on that single day of infamy almost half a century back-more than twenty-five hundred others were wounded-a greater number of military casualties on just that single day than the total in all but the longest, bloodiest engagements in the Pacific, more than on D day in France.

No wonder we finally went in.

Thank God for the atom bomb, I rejoiced with the rest of the civilized Western world, almost half a century ago, when I read the banner newspaper headlines and learned it had exploded. By then I was already back and out, unharmed and, as an ex-GI, much better off than before. I could go to college. I did go and even taught college for two years in Pennsylvania, then returned to New York and in a while found work as an advertising copywriter in the promotion department of Time magazine.

In only twenty years from now, certainly not longer, newspapers across the country will be printing photographs of their oldest local living veterans of that war who are taking part in the sparse parades on the patriotic holidays. The parades are sparse already.

I never marched. I don't think my father did either. Way, way back, when I was still a kid, crazy Henry Markowitz, an old janitor of my father's generation in the apartment house across the street, would, on Armistice Day and Memorial Day, dig out and don his antique World War I army uniform, even down to the ragged leggings of the earlier Great War, and all that day strut on the sidewalk back and forth from the Norton's Point trolley tracks on Railroad Avenue to the candy store and soda fountain at the corner of Surf Avenue, which was nearer the ocean. Showing off, old Henry Markowitz-like my father back then, old Henry Markowitz probably was not much past forty-would bark commands out till hoarse to the tired women trudging home on thick legs to their small apartments carrying brown bags from the grocery or butcher, who paid him no mind. His two embarrassed daughters ignored him too, little girls, the younger my own age, the other a year or so older. He was shell-shocked, some said, but I do not think that was true. I do not think we even knew what shell-shocked meant.

There were no elevators then in our brick apartment houses, which were three and four stories high, and for the aging and the elderly, climbing steps, going home, could be hell. In the cellars you'd find coal, delivered by truck and spilled noisily by gravity down a metal chute; you'd find a furnace and boiler, and also a janitor, who might live in the building or not and whom, in intimidation more than honor, we always spoke of respectfully by his surname with the title "Mister," because he kept watch for the landlord, of whom almost all of us then, as some of us now, were always at least a little bit in fear. Just one easy mile away was the celebrated Coney Island amusement area with its gaudy lightbulbs in the hundreds of thousands and the games and rides and food stands. Luna Park was a big and famous attraction then, and so was the Steeplechase ("Steeplechase-the Funny Place ") Park of a Mr. George C. Tilyou, who had passed away long before and of whom no one knew much. Bold on every front of Steeplechase was the unforgettable trademark, a striking, garish picture in cartoon form of the grotesque, pink, flat, grinning face of a subtly idiotic man, practically on fire with a satanic hilarity and showing, incredibly, in one artless plane, a mouth sometimes almost a city block wide and an impossible and startling number of immense teeth. The attendants wore red jackets and green jockey caps and many smelled of whiskey. Tilyou had lived on Surf Avenue in his own private house, a substantial wooden structure with a walkway to the stoop from a short flight of stone steps that descended right to the margin of the sidewalk and appeared to be sinking. By the time I was old enough to walk past on my way to the public library, subway station, or Saturday movie matinee, his family name, which had been set in concrete on the vertical face of the lowest step, was already sloping out of kilter and submerged more than halfway into the ground. In my own neighborhood, the installation of oil burners, with the excavations into the pavement for pipes and fuel tanks, was unfailingly a neighborhood event, a sign of progress.

In those twenty more years we will all look pretty bad in the newspaper pictures and television clips, kind of strange, like people in a different world, ancient and doddering, balding, seeming perhaps a little bit idiotic, shrunken, with toothless smiles in collapsed, wrinkled cheeks. People I know are already dying and others I've known are already dead. We don't look that beautiful now. We wear glasses and are growing hard of hearing, we sometimes talk too much, repeat ourselves, things grow on us, even the most minor bruises take longer to heal and leave telltale traces.

And soon after that there will be no more of us left.

Only records and mementos for others, and the images they chance to evoke. Someday one of the children-I adopted them legally, with their consent, of course-or one of my grown grandchildren may happen upon my gunner's wings or Air Medal, my shoulder patch of sergeant's stripes, or that boyish snapshot of me -little Sammy Singer, the best speller of his age in Coney Island and always near the top of his grade in arithmetic, elementary algebra, and plane geometry-in my fleecy winter flight jacket and my parachute harness, taken overseas close to fifty years back on the island of Pianosa off the western shore of Italy. We are sitting with smiles for the camera near a plane in early daylight on a low stack of unfused thousand-pound bombs, waiting for the signal to start up for another mission, with our bombardier for that day, a captain, I remember, looking on at us from the background. He was a rambunctious and impulsive Armenian, often a little bit frightening, unable to learn how to navigate in the accelerated course thrown at him unexpectedly in operational training at the air base in Columbia, South Carolina, where a group of us had been brought together as a temporary crew to train for combat and fly a plane overseas into a theater of war. The pilot was a sober Texan named Appleby, who was very methodical and very good, God bless him, and the two were very quickly not getting along. My feelings lay with Yossarian, who was humorous and quick, a bit wild but, like me, a big-city boy, who would rather die than be killed, he said only half jokingly one time near the end, and had made up his mind to live forever, or at least die trying. I could identify with that. From him I learned to say no. When they offered me another stripe as a promotion and another cluster to my Air Medal to fly ten more missions, I turned them down and they sent me home. I kept all the way out of his disagreements with Appleby, because I was timid, short, an enlisted man, and a Jew. It was my nature then always to make sure of my ground with new people before expressing myself, although in principle at least, if not always with the confidence I longed for, I thought myself the equal of all the others, the officers too, even of that big, outspoken Armenian bombardier who kept joking crazily that he was really an Assyrian and already practically extinct. I was better read than all of them, I saw, and the best speller too, and smart enough, certainly, never to stress those points.

Next page