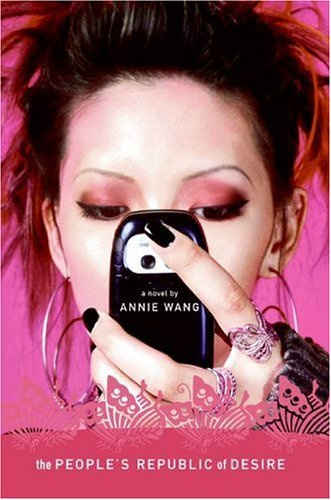

Annie Wang

The Peoples Republic of Desire

I first thought of writing this book in 2000 while I was staying at a hotel in Hong Kong overlooking Victoria Harbor. It was March then. When I left my home in California, the tulips and roses in the garden were blooming: blue, yellow, and white. The peaches and pear trees were in bloom as well. When the wind blew, it scattered peach and plum blossoms onto the stone path in my garden, reminding me of the poetry of my favorite Song Dynasty female poet, Li Qingzhao.

I love ancient China, but I live in modern China. And, at least in the case of this paradox, time is the eternal victor.

I have chosen to lead this life going back and forth between East and West, China and the United States. I feel like a migratory bird traveling across the globe with the changing seasons.

For what? Stories, perhaps. In 2000, I gave up my job in Silicon Valley when "information technology," "Internet," "initial public offering," and "venture capital" were the hottest concepts in the world. I went back to China looking for interesting stories for the Washington Post. I told myself that I am a story collector of the poor, not the rich.

Looking out onto Victoria Harbor and at the skyscrapers standing out against the sky, I felt a battery of complex feelings well up in my heart. And I realized that I was thinking in Chinese again.

After years of living in the Bay Area, I had grown accustomed to talking about multiculturalism, spiritual paths, faith, identity, and the notion of belonging. Back in China, I hear people discuss at length the experience of their first taste of Starbucks coffee, the first time they drove a Buick, chatting on the Internet, experiencing a one-night stand or watching an adult movie. Divorce, oral sex, affairs, boob jobs, abortion, homosexuality, overcharged libidos, impotence these once-taboo subjects have become daily conversations among urban women who take great pride in owning a bottle of Chanel No. 5. It's cool to be a sex dissident as long as you are not a political dissident. Conservativeness is a dirty word.

At the same time, Cuban cigars, Giorgio Armani, BMWs, and golf clubs are introduced to successful Chinese men as the symbol of their yuppie lifestyle. They hire young poor peasant boys as their bodyguards and take young poor peasant girls as their playmates.

No one remembers what happened at Tiananmen Square in 1989. Nor are they concerned with China 's political future. Money and status rule the day. It seems only two types of people exist: those who admire power and wealth, and those who are being admired for their power and wealth.

China, this ancient civilization that was once suffocated under the weight of its own history, has changed so drastically, so swiftly, it is far beyond the comprehension of the Chinese themselves, let alone outsiders and the go-betweens, such as me, who are known as American Chinese or Chinese Americans.

These are unspeakably crazy and illogical times. Dynamic. Impulsive. Pragmatic. Chaotic. Brimming with desire. Cheeky. Declining. Contradictory. A time when it's more shameful to be poor than to be a whore. And, at the same time, it's an era full of glory, dreams, and primitive passions. In China, everything is laid bare. There are no secrets.

I thought to myself, forget about identifying and belonging. It has never been that important, anyway. The word "home" needs to be redefined.

What the Chinese need is a solution to the problems of modernization, for themselves as individuals, and for Chinese civilization as a whole.

The Chinese once carried so much cultural baggage. We used to laugh with teary eyes, obsessed with the memories of humiliation and sorrow, wrenched to the gut with love and hate. We acted with impulsive nationalism and with the shame of defeat. We waited with painful anxiety, overcome by uncontrollable fervor.

Perhaps a little fast food frivolity, a little Starbucks shallow-ness, a little Hong Kong style materialism, a little ignorance and indifference of history simply are necessary for the new market economy. Kick back, relax, and, only then, amid the void, will China and the Chinese be able to find a way out.

That night, my thoughts slipped out of American and back into Chinese. I drank too much at Lan Kwai Fong Hong Kong with my girlfriends. In a postcolonial bar, we, a group of self-professed intelligent female graduates of distinguished American and British universities, found we were unable to define the notions of home and roots. Imported liquor, cigars, and loud music were for us a kind of comfort. Even though we shed tears that night, we still felt a temporary sense of security.

The next day, I went to a quaint, poor fishing village, stood on the dilapidated pier, and filled my nostrils with the smell of drying fish. The live sea animals in fish tanks, the skillful killing of these animals, the poor housing these are the images of China that are being broadcast familiar in the West. With a shirt tied round my waist and waving my expensive digital camera, I wandered around with the other foreign tourists, gazing left and right with curiosity. I even faced the sea, stretched out my arms, and said, "This is life!" like a character from a typical Chinese melodrama. Am I like a foreign tourist who is searching for exoticism in my home country or is the whole world becoming Westernized?

When I was fourteen, I fell in love with the Indian author Tagore and a line from one of his meditative poems: "Wisdom reaches the peak of perfection in drunkenness." So many years have passed, and I still have not found an aphorism better than that damn line. I haven't learned anything.

There was a time when I was heavy-hearted, all for the sake of writing, metaphysics, and the future of Chinese civilization. Who did I think I was? Only later did I understand how foolish I was. Now, I'm drunk with reality. No more a serious, obstinate, foolish intellectual. I want to be free-falling, free-falling with a China that is no longer homely.

I am casting off my burdens no more will I play the role of a Confucian intellectual.

After all, aren't we the new breed? Aren't we young? Aren't we lonely modern souls? Don't we deserve to be happy and carefree? Don't we need a little fun? So let's play. After all, we have always been good at games.

"Returnee" is a popular word nowadays in China, especially since the Chinese government called on all "patriotic overseas Chinese" to return to their homeland to build a "modern, strong China."

These returnees have a number of common traits.

First, they don't normally wear miniskirts or makeup, like so many local girls do. They often don't look very fashionable and seem to care little about such frippery.

Second, they have usually obtained advanced degrees somewhere in the West and often like to say, as casually as possible, "I went to school in Boston." (But they never forget to wear their Harvard or Yale rings on their fingers.)

Third, they are timid pedestrians. It takes them forever to cross an average Chinese road.

Fourth, they don't smoke. In fact, they get dizzy around smokers.

Fifth, they don't like people to ask where they come from, especially someone who has just met them. If they are prodded for an answer, they tend to pause for several seconds as if faced with a multiple-choice question. If they were to give the traditional response, they would tell the inquirer the birthplace of their fathers' ancestors. Knowing your ancestors' birthplace and tomb sites demonstrates that you haven't forgotten your roots. Anyone who forgets his roots is despised and accused of being a sellout. In China the phrase, "He doesn't know his last name anymore," is hurled to mock those who try to forget their roots.

Next page