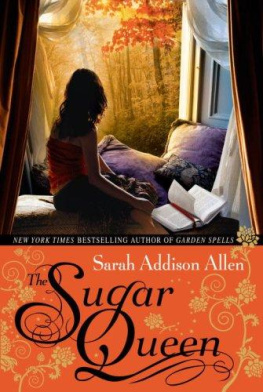

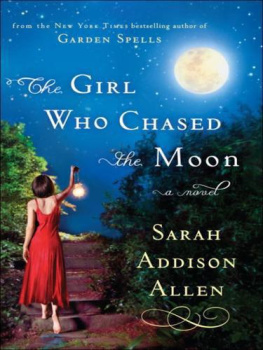

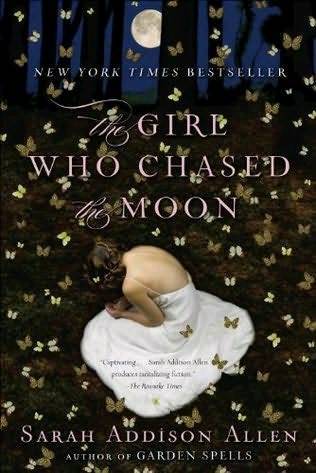

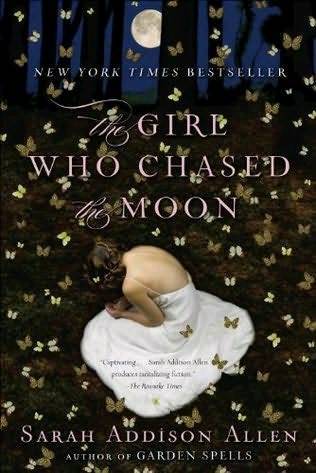

Sarah Addison Allen

The Girl Who Chased the Moon

2009

To the memory of famous gentle giant

Robert Pershing Wadlow (1918-1940).

At the time of his death at age twenty-two,

he was eight feet eleven inches tall-

a world record that has never been broken.

It took a moment for Emily to realize the car had come to a stop. She looked up from her charm bracelet, which shed been worrying in slow circles around her wrist, and stared out the window. The two giant oaks in the front yard looked like flustered ladies caught mid-curtsy, their starched green leaf-dresses swaying in the wind.

This is it? she asked the taxi driver.

Six Shelby Road. Mullaby. This is it.

Emily hesitated, then paid him and got out. The air outside was tomato-sweet and hickory-smoked, all at once delicious and strange. It automatically made her touch her tongue to her lips. It was dusk, but the streetlights werent on yet. She was taken aback by how quiet everything was. It suddenly made her head feel light. No street sounds. No kids playing. No music or television. There was this sensation of otherworldliness, like shed traveled some impossible distance.

She looked around the neighborhood while the taxi driver took her two overstuffed duffel bags out of the trunk. The street consisted of large old homes, most of which were showpieces in true old-movie Southern fashion with their elaborate trim work and painted porches.

The driver set her bags on the sidewalk beside her, nodded, then got behind the wheel and drove off.

Emily watched him disappear. She tucked back some hair that had fallen out of her short ponytail, then grabbed the handles of the duffel bags. She dragged them behind her as she followed the walkway from the sidewalk, through the yard and under the canopy of fat trees. It grew dark and cold under the trees, so she picked up her pace. But when she emerged from under the canopy on the other side, she stopped short at the sight before her.

The house looked nothing like the rest of the houses in the neighborhood.

It had probably been an opulent white at one time, but now it was gray, and its Gothic Revival pointed-arch windows were dusty and opaque. It was outrageously flaunting its age, spitting paint chips and old roofing shingles into the yard. There was a large wraparound porch on the first floor, the roof of which served as a balcony for the second floor, and years of crumbling oak leaves were covering both. If not for the single clear path formed by use up the center of the steps, it would have looked like no one lived there.

This was where her mother grew up?

She could feel her arms trembling, which she told herself was from the weight of the bags. She walked up the steps to the porch, dragging the duffel bags and a good many leaves with her. She set the bags down and walked to the door, then knocked once.

No answer.

She tried again.

Nothing.

She tucked her hair back again, then looked behind her as if to find an answer. She turned back and opened the rusty screen door and called into the house, Hello? The space sounded hollow.

No answer.

She entered cautiously. No lights were on, but the last sunlight of the day was coughing through the dining room windows, directly to her left. The dining room furniture was dark and rich and ornate, but it seemed incredibly large to her, as if made for a giant. To her right was obviously another room, but there was an accordion door closing off the archway. Straight in front of her was a hallway leading to the kitchen and a wide staircase leading to the second story. She went to the base of the stairs and called up, Hello?

At that moment, the accordion door flew open and Emily jumped back. An elderly man with coin-silver hair walked out, ducking under the archway to avoid hitting his head. He was fantastically tall and walked with a rigid gait, his legs like stilts. He seemed badly constructed, like a skyscraper made of soft wood instead of concrete. He looked like he could splinter at any moment.

Youre finally here. I was getting worried. His fluid Southern voice was what she remembered from their first and only phone conversation a week ago, but he was nothing like she expected.

She craned her neck back to look up at him. Vance Shelby?

He nodded. He seemed afraid of her. It flustered her that someone this tall would be afraid of anything, and she suddenly found herself monitoring her movements, not wanting to do anything to startle him.

She slowly held out her hand. Hi, Im Emily.

He smiled. Then his smile turned into a laugh, which was an ashy roar, like a large fire. Her hand completely disappeared in his when he shook it. I know who you are, child. You look just like your mother when she was your age. His smile faded as quickly as it had appeared. He dropped his hand, then looked around awkwardly. Where are your suitcases?

I left them on the porch.

There was a short silence. Neither of them had known the other existed until recently. How could they have run out of things to say already? There was so much she wanted to know. Well, he finally said, you can do what you want upstairs-its all yours. I cant get up there anymore. Arthritis in my hips and knees. This is my room now. He pointed to the accordion door. You can choose any room you want, but your mothers old room was the last one on the right. Tell me what the wallpaper looks like when you walk in. Id like to know.

Thank you. I will, she said as he turned and walked away from her, toward the kitchen, his steps loud in his wondrously large shoes.

Emily watched him go, confused. That was it?

She went to the porch and dragged her bags in. Upstairs, she found a long hallway that smelled woolly and tight. There were six doors. She walked down the hall, the scraping of her duffel bags magnified in the hardwood silence.

Once she reached the last door on the right, she dropped her duffel bags and reached to the inside wall for the light switch. The first thing she noticed when the light popped on was that the wallpaper had rows and rows of tiny lilacs on it, like scratch-and-sniff paper, and the room actually smelled a little like lilacs. There was a four-poster bed against the wall, the torn, gauzy remnants of what had once been a canopy now hanging off the posts like maypoles.

There was a white trunk at the foot of the bed. The name Dulcie, Emilys mothers name, was carved in it in swirly letters. As she walked by it, she ran her hand over the top of the trunk and her fingertips came away with puffs of dust. Underneath the age, like looking though a layer of ice, there was a distinct impression of privilege to this room.

It made no sense. This room looked nothing like her mother.

She opened the set of French doors and stepped out onto the balcony, crunching into dried oak leaves that were ankle-deep. Everything had felt so precarious since her mothers death, like she was walking on a bridge made of paper. When shed left Boston, it had been with a sense of hope, like coming here was going to make everything okay. Shed actually been comforted by the thought of falling back into a cradle of her mothers youth, of bonding with the grandfather she hadnt known she had.

Instead, the lonely strangeness of this place mocked her.

This didnt feel like home.

She reached to touch her charm bracelet for comfort, but felt only bare skin. She lifted her wrist, startled.

Next page