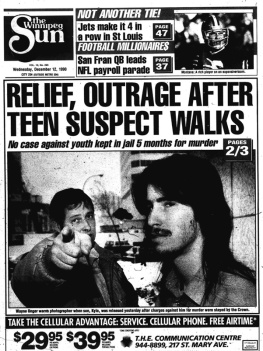

Claire was so sure her abusive husband would kill her that she took out a life insurance policy the day she saw a lawyer about a divorce.

Natashas beautiful face and skull had been crushed by the crowbars blows, but her mind refused to forget who had done it.

Victoria Doom had no idea that taking on Natashas case would make her the target of a hit man.

Steve Fisk was haunted by the fates of Natasha and Claire, sworn to find the perpetrator, and determined to put him away.

Robert Peernock had money, a plan, plastic surgery, and a girlfriend to help him escape but his twisted brain had left one damning piece of evidence behind.

Contents

PART I

PART II

PART III

PART IV

TORTURE: An extreme physical and mental assault on a person who has been rendered defenseless.

Amnesty International

CHAPTER

1

S he lay in the seat listening to the metallic sounds as he tinkered under the Cadillac. Was it safe to move?

She still had a little physical control left, despite her cuffed hands, her bound ankles, her blindness inside the canvas hood. But long hours in captivity being force-fed a combination of alcohol and some kind of an unknown drug had served to take a severe toll. Even though she was a healthy eighteen-year-old and had always been athletic, by this point it took all her effort just to make her slim body obey her.

She reached out over her mothers unconscious form. Slowly, she ran trembling fingers down the steering column until at last her fingertips brushed the ignition. The key was still there, but she pulled back. Could she start the car even though her hands were cuffed in front of her? Could she shift the transmission into reverse even though she couldnt see, stomp on the gas even though her feet were tied? Most of all, could she do it fast enough to run the car over him before he heard her and scrambled out of the way? She had to try. There was no longer any doubt that he was about to kill them both. Once again she leaned over her mother, stretching her cuffed hands out toward the key.

But just as her fingertips finally reached the ignition, she realized the sounds under the car had stopped.

Sometime before 4:00 A.M. on July 22, 1987, a motorist named John Dozier pulled over to the side of a desolate road. He peered into the early morning darkness and struggled to focus on a jumble of twisted wreckage off the right-hand shoulder. It seemed to be a single car wreck; no one was moving at the scene.

He looked closer. A thin wisp of smoke was rising from the undercarriage of an old Cadillac resting near the side of the road. The rear of the car was still on the gravel shoulder, but the front straddled the remains of a wooden telephone pole. It appeared that the heavy 71 sedan had rammed the pole with such force that it had splintered and collapsed. The front of the car had come to rest on top of the remains of the pole as it lay on the ground.

Dozier realized that the wreck must have happened only moments before and that he was the first to come along. He knew that on an isolated strip of road like this one, it might be hours before anyone else chanced by in the darkness.

He hurried over, opened the drivers door of the Cadillac and discovered a petite woman lying inside. She gave no signs of life. He tried to pull her free but she was jammed under the dashboard beneath the steering wheel. On the floor beside her he could hear a female passenger moaning softly, but the door on the passenger side was jammed in place and there was nothing he could do to free the second victim either.

Then he remembered the thin wisp of smoke rising from under the car. He realized an explosion could happen at any second.

Dozier hurried away to find a phone and call for help.

At 4:25 on that same July morning, Paramedic Clyde Piehoff was sleeping through the quiet hours of a twenty-four-hour shift at Fire Station 89 in the North Hollywood area of Los Angeles when he received a radio dispatch over his hotline. The call came from the main dispatch center in downtown L.A., located five riot-proof floors below ground level. The order directed him to proceed to San Fernando Road near the Tuxford intersection in the neighboring town of Sun Valley. Clyde was a supervisor with the rank of paramedic 3, serving all county municipalities, so the call was within his jurisdiction. He summoned his partner, Paramedic 2 Todd Carb, and their trainee, Paul Egizi. Within moments they were rolling toward the scene.

Clydes problems began immediately; there are two San Fernando Roads that intersect Tuxford. He made his best guess and arrived shortly afterward at what he considered the more commonly traveled of the two locations: the new strip of road, where most of the traffic could be expected to go.

There was nothing there.

Knowing he was losing precious seconds, he and his crew rushed toward old San Fernando Road, a lesser used strip of dead-end road running slightly north of a set of railroad tracks. There they finally spotted the dispatch incident.

Four minutes had elapsed since their call came in.

Clyde saw the first body before he and the crew had even exited their ambulance. The woman lay on the floor under the steering wheel, her back against the drivers seat and her head slumped against the door frame. Her knees were jammed up under the dashboard, with her right arm on the floor and her left arm trailing out of the open drivers side door and onto the ground.

He did not notice the missing section of the underside of the dash or the exposed brackets for mounting stereo equipment, because in his mind, the woman became Clydes patient the moment he arrived on the scene.

Visibility inside the car was a problem; the dome light was not on, even though the drivers side door was open. His attention was already fixed on assessing her condition. But he suspected that once he reached the woman his check for vital signs would be useless; in addition to clear evidence of massive blood loss, Clydes patient had sizable portions of brain matter exposed just above her eyes.

After his first quick check of the woman hanging out of the doorway, Clyde saw a second body on the floor of the passenger side. The second passenger, also a female, wasnt moving either. He called for Todd and Paul to circle around the car to look after the second passenger while he knelt by the drivers side passenger to continue his preliminary assessments.

The smell of gas is typical in bad car wrecks, but Clyde noticed that the odor from this wreck was unusually strong. Glancing around the interior of the car, he saw puddles of fluid on the floorboards. Alarmed that they could be dealing with an active fuel leak, Clyde quickened his pace.

In that first brief moment he had also noticed that blood was also splattered across the inside of the windshield and over the gearshift area. But there was, oddly, no damage at all to the windshield itself or the steering column.