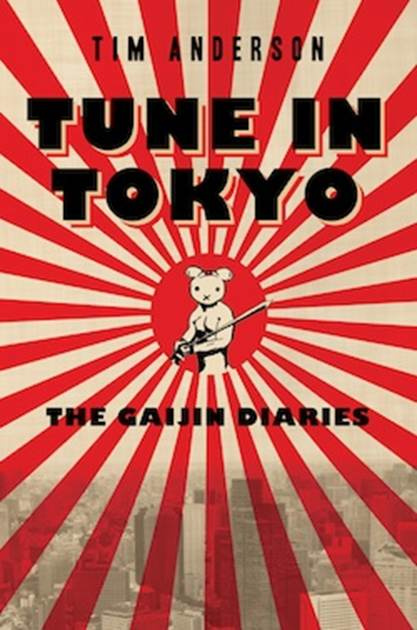

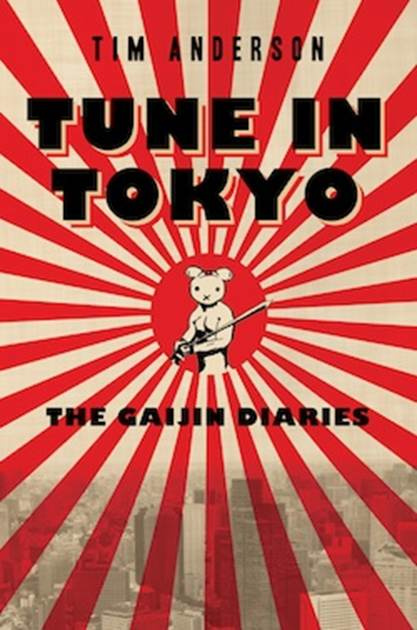

Tim Anderson

Tune in Tokio

Text copyright 2011 Tim Anderson

For Little Man Jimmy.

And for Kelly Guffey (1973-2006), who sure would have laughed.

(rememberkelly.org)

Like everyone, I was deeply saddened by the tragic events that took place in northern Japan in March 2011. In communication with my Japanese friends during the weeks afterward, one sentiment that many of them expressed was the need to have a diversion from the horror and the fear. One friend said, in imperfect but beautiful English, we shouldnt forget victims, but we need to release our mind apart from this sometime. Otherwise we are stifled with the sadness Tune in Tokyo is a light-hearted romp through Japans capital, my love letter to the city and its people. I hope in some small way it can, perhaps, provide a silly diversion for those Japanese folks who happen upon it. And for all those other readers, that it will leave them with a smile on their face when they think of Japan.

I got the style but not the grace,

I got the clothes but not the face,

I got the bread but not the butter,

I got the winda but not the shutter,

But Im big in Japan.

Tom Waits

Q and A; or, Im So Bored with the USA

gaijin,

n. 1. foreigner, outsider

2. pest, big fat alien, one who must be stared at on trains

Why do I to be being here?

This question comes to me one evening when I am in the midst of a two-hour class with two extremely low-level students at the English conversation school where I teach in central Tokyo. Hiromi, Kiyomi, and I are concentrating on question formation: when, where, and, of course, what. They practice asking each other questions in a get-to-know-you kind of exercise, with results like, What is your sports do you like? and, When is month on your birthday? Then we come to the why.

Can you think of a why question to ask Kiyomi? I ask Hiromi slowly, doubtfully. She stares at me with fear and trauma, as if Ive just asked her to implicate her mother in the murder of her father.

Ive had my share of shit-scared students today, and now I have two more. Its like spending two hours trying to coax a cat out from under the bed: she may take a few steps, but one careless move on your part will have her scurrying out of reach once again, leaving you to pull your hair out.

Staring out the window at the electric Tokyo sky and the Sapporo beer advertisement on a neighboring building-an ad featuring two be-suited Japanese tough guys looking directly at me and asking the pivotal question in English, Like Beer?-I come up with a why question of my own:

Why would a college graduate with such impeccable credentials as a BA in English, diabetes, credit card debt, Roman nose, and a fierce and unstoppable homosexuality want to leave the boundless opportunities available to him in the USA (temping, waiting tables, getting shot by high school students) for a tiny, overcrowded island heaving with clever, sensibly proportioned people who make him look fat?

Before I left the U.S., I couldnt figure out what path I wished to tread, like every other lazy, listless Libran of my generation. I was American by birth, Southern by the grace of God, living in my hometown of Raleigh, North Carolina.

I had three part-time jobs and one boyfriend (the reverse of which being far preferable). Brightleaf, a Southern literary journal, was great work experience, Southern fiction being the hot literary genre of the moment, with most of the country only recently realizing that most Southerners can actually read and write without the aid of a spittoon. Here I had the opportunity to read and edit some truly inspired writing. The main problem with this job was the wage: slightly less than that earned by American Heart Association volunteers.

Job #2 was at the Rockford, a downtown restaurant, waiting tables a few nights a week. Here I was nothing if not a jaded waitperson, kind of like Flo on Alice, minus the exceptional hairstyle and the long line of trucker boyfriends. (Sigh.) Whenever I found myself encouraging my customers to have a nice day, I had to stop and ask myself, Do they deserve such kindness after giving me just eleven percent?

Thankfully, the restaurant was as laid-back as they come: no uniform, no split checks, and, praise be to God, no baby chairs. Still, I didnt like the person waiting tables was turning me into. When I bid farewell to my customers as they walked down the stairs to the street below, I didnt see people; I saw walking, talking digestive tracts. I saw beer, veggie burgers, and strawberry cheesecakes sloshing around in stomachs. I saw innards. And I didnt like what I saw.

Which was why Id sought out job #3. Since I wasnt making enough money at the magazine and couldnt bear the thought of working more than a few shifts a week at the restaurant, I found myself teaching English at the local Berlitz Language Center. A few days a week, I instructed Japanese businessmen on how to communicate effectively (more or less) and confidently (kind of) in a language they feared more than Godzilla.

We dont just want the best teachers in Raleigh at our school, the head instructor at the school told me during my interview. We want the best teachers in the world. A bold statement, and a bizarre one, since their pay rate was on par with the checkout girls at the local Food Lion, and God knows they werent the best in the world. If Berlitz expected me to rate with inspirational teachers across the globe, shouldnt they look into paying me more than seven dollars for a forty-five-minute lesson?

Still, it was a job I was happy doing, so I didnt much care about pay. I was getting to know people from all over the place: Mexico, Puerto Rico, Japan, France, Italy, Brazil, Korea. For a few hours a few days a week, I was able to relieve myself of my homegrown ennui and make contact with the outside world.

Because contact with the outside world was what I desperately needed. Somehow, over the years, I had devolved from a social, reasonably charismatic soul who thrived on meeting new people into an introverted, cloistered, and feckless pothead approaching the ripe old age of thirty who rarely explored the world beyond his television screen. Once an attention-whoring child of the stage-with a rsum that included major bit parts in many local Little Theater productions-and an excitable, if music theory-challenged, violin and viola player in school and music camp orchestras, I was now a hopeless recluse with absolutely no confidence, too shy to even pick up my viola and play it for close friends for fear of hitting a wrong note and driving them into the arms of another gay who would better serve their entertainment needs. How had this happened? If the thirteen-year-old me could see me now, he would shake his head, tut-tut, and launch into a wispy rendition of some minuet or other. Then he would look me up and down and slap me in my face.

I looked at my viola, listlessly leaning against its case in my bedroom, aching to be touched, caressed, and gripped forcefully yet lovingly by expert hands. I hadnt picked it up in many months, and the last time I had, Id gotten the distinct impression that the viola was trying to tell me it would really rather I put it down and find a nice young five-year-old music student to sell it to.

Next page