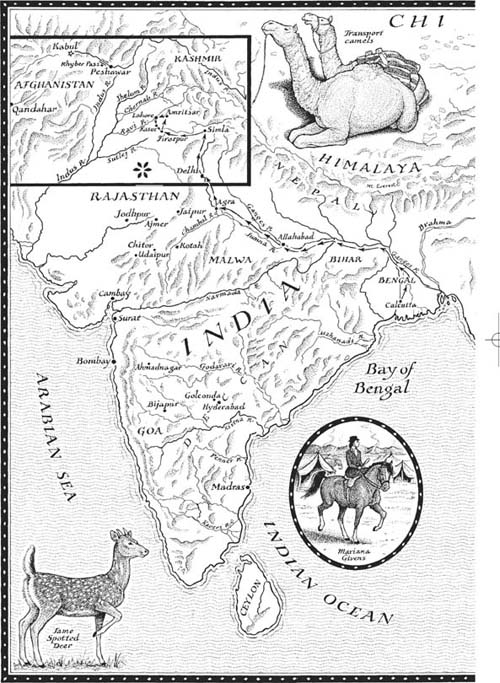

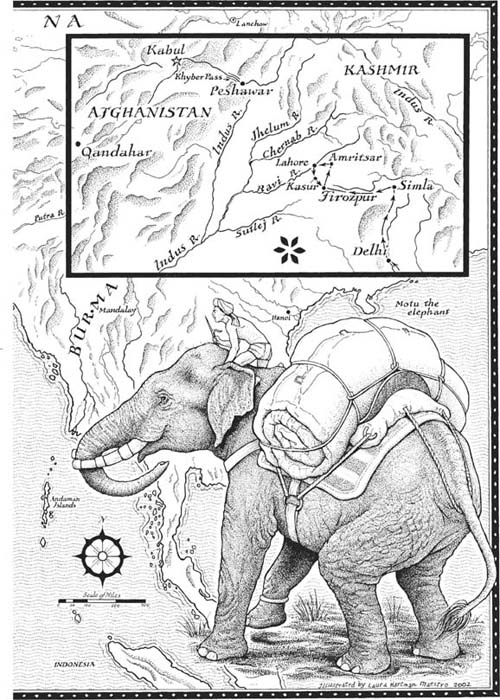

T his story takes place in the north of India, now Pakistan, in 18381839, the first year of Queen Victoria's reign. By that year, Britain, through its proxy, the Honorable East India Company, controlled most of the Indian subcontinent. To the north, the Great Gamethe nineteenth-century struggle between Britain and Russia for control of Central Asiawas gathering speed.

By 1838, the British feared a Russian threat to their Indian territories. Determined to outwit the Russians by gaining political control of Afghanistan, Lord Auckland sent his armies to Kabul on a military adventure later known as the First Afghan War.

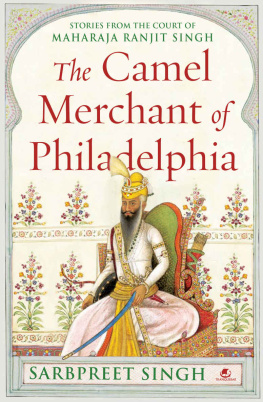

Before launching his Afghan Campaign, Auckland took the extraordinary step of traveling twelve hundred miles across India to enlist the aid of the dying one-eyed Maharajah Ranjit Singh of the Punjab, whose independent military state lay between the British territories and Afghanistan. That year-long journeyon which Lord Auckland was accompanied by his two spinster sisters, his entire government, and a ten-thousand-man armyculminated in the great durbar, or state meeting, at Firozpur, on the border between Britishcontrolled India and the Punjab.

A treaty between the two was essential to the British campaign. Maharajah Ranjit Singh knew this and delayed signing the treaty for a month, forcing Auckland to send his troops across the mountain passes into Afghanistan in deep winter.

This story takes place during that month.

LORD Auckland, his sisters, his political secretary, and his chief of protocol are real historical figures, as are Maharajah Ranjit Singh and his Chief Minister. The durbar took place much as I have described it, and the subsequent movements of the British camp are generally accurate.

Mariana Givens, Harry Fitzgerald, the baby Saboor and his family, and Saat Kaur, the Maharajah's youngest wife, are products of my imagination.

A t 2:00 A.M., Shaikh Waliullah Karakoyia opened his eyes. Years of offering his prayers at the ppointed hours had given him a delicate sense of the passage of time. Sometimes he allowed himself to imagine that, should he be sent to the windowless dungeons of the Lahore Citadel, whose walls shut out the call to prayer, he would still know when to wash himself and stand before his God.

He shivered and reached for his shawl. Moonlight filtered its way through the latticework balcony outside and fell like coins on the prayer rug that lay ready, pointing west to Mecca, its corner turned back to avert evil. Wooden curtain rings clicked softly as he padded through a doorway to the little table that held his water vessel and brass basin. The water was cold as he washed for the postmidnight prayer, a prayer optional to all save those schooled in the mystical traditions of Islam.

God is great, he murmured, as he dried his face.

Facing the wall so that no creature might come between him and God, the Shaikh stood straight, his hands folded, his eyes half-closed.

In the name of Allah Most Gracious, Most Merciful:

Praise be to Allah, Cherisher and Sustainer of the Worlds;

Most Gracious, Most Merciful,

Master of the Day of Judgment.

Thee alone we worship, Thee alone we ask for help.

Guide us to the straight path: the path of those whom Thou

hast favored;

Not of those who have earned Thy wrath, nor of those who

have gone astray.

As he recited, he abandoned himself to his dreams: mind pictures so dazzling that he found them difficult to describe, even to the most advanced members of the mystic brotherhood he had led for more than twenty-five years.

Eyes on the mat before him, the Shaikh moved through the slow dance of his prayer. He bent, straightened, and bowed, his forehead to the tiles beneath the threads of his prayer mat, as his fellow Muslims had done for thirteen hundred years, the venerable Arabic coming in whispered cadences in the moonlight.

BY sunrise, the rain that had poured in torrents before dawn had nearly ceased, leaving only a faint light to shine on the Shaikh's house and on the cobbled square upon which it stood.

The light strengthened and found its way into the narrow lanes and bazaars of Lahore City. It spread over the wet pavilions and courtyards of Maharajah Ranjit Singh's Citadel, the great marble fort that shared with the city the protection of its ancient fortified wall.

In an octagonal tower set into the Citadel's northwest corner, the Maharajah's youngest hostage was refusing a cup of milk.

Saboor would not drink from the cup the servant girl held out invitingly. Compressing his lips, he turned his head away.

Oh, Saboor Baba, the girl crooned, looking about her cautiously as she held out the cup, drink this, it is sweet.

No, said the child firmly, and trotted away, his little shoulders bouncing. Reaching the safety of the bed where his mother sat loosening her hair, he crouched beside her and followed the servant with round, anxious eyes.

What is the matter, my darling? His mother pursed her lips and made a kissing sound. Why don't you want your milk? You love your milk. Cocking her head, Mumtaz Bano studied Saboor and smiled. Auburn hair cascaded over her shoulder and lay in a shining coil in her lap.

Oh, Reshma, is Saboor not the sweetest baby in all of Lahore? she asked in her child's voice.

Yes, Bibi, murmured the servant girl, her head swaying in agreement. The cup she held trembled, making little waves in the milk.

But Saboor would not have his milk. He crawled beneath the bed, his bare feet disappearing from view. There he sat, obstinately refusing his breakfast.

Well, then, your ammi will have to drink it instead, his mother said. Ammi loves warm sweet milk.

Mumtaz Bano reached for the cup, heavy embroidered silk falling back from a delicate wrist. The servant, her eyes widening, tried to take it back. No, Bibi. This milk is for Saboor, she protested, but Mumtaz Bano would have it. She made a polite but commanding gesture.