Joseph O'Neill

Blood-Dark Track

To the memory of Joseph Dakad (18991964) and

James ONeill (19091973); to my sons; and to Sally.

This book is largely the product of help I have received from my family, Turkish and Irish. As regards the latter, I am grateful, first and foremost, to my grandmother, Eileen ONeill, who freely lent herself to a project that, by its nature, was troubling to her. I owe a similar debt of gratitude to Jim ONeill, Terry ONeill, Ann Pollock-ONeill and Marian OSullivan-ONeill, who shared thoughtful and sensitive insights into the character and life of my Irish grandfather, Jim ONeill. My greatest debt, here, is to Brendan ONeill. His generosity of spirit and willingness to reflect openly on sensitive historical issues made a huge contribution to this book. I also wish to thank, in relation to the Irish story, Acushla Bastible, Pat Buckley, Con and Oriana Conner, Dan Daly, Antony Farrell, Mick Fitzgibbon, Derry and Phyllis Kelleher, Paddy Lynch, Peig Lynch, Frank and Mary Morris, Barney McFadden, Angela McEvoy-ONeill, Shammy OConnell, Pat ONeill, Sen ONeill, Mary OSullivan, Billy Pollock, Mrs Salter-Townshend, Brendan Sealy, Christopher Somerville. John Bowyer Bell was an essential source of information about the shooting of Admiral Somerville and pre-Emergency republicanism generally. My heavy reliance on the work of Peter Hart and Uinseann MacEoin will be evident to readers.

Amy Dakads translation of Joseph Dakads testimony is the foundation of my inquiry into my Turkish grandfathers life, and I am enormously appreciative of her work. I am deeply grateful for the scholarship and friendly help of Sir Denis Wright, whose influence on this book has been vital. I also wish to thank, in relation to the Turkish story, Florent Arnaud, Sara Bershtel, Ginette Estve, Patrick Grigsby, the late Professor O.R. Gurney, Brother Guy of Latrun, the late Bill Henderson, Haidar Husseini, the Kurdish Human Rights Project, Tim Ottey, Denis Ryan, Tom Segev, Astrid Seime, Yitzhak Shamir, Yves-Marie Villedieu, the late Lolo Zahlout. I wish to acknowledge the contribution of my late great-aunts, Alexandra and Isabelle Nader, and grandmother, Georgette Dakad.

A variety of institutions enabled my research, in particular the Middle East Centre at St Antonys College, Oxford; the New York Public Library; the British Library. While I wrote the book, my unlucrative presence was tolerated by the staff and proprietors of La Bergamote (thank you, Romain Lamaze); the Malibu Diner; and the Riss Restaurant. Bob and Nan Stewart were wonderfully hospitable to me in Ontario, Canada.

The following helped me in various ways: Shari Anlauf, Tom Astor, Pete Ayrton, Matthew Batstone, David Bieda, Daniel Bobker, Susie Boyt, Philippe Carr, Monique El-Faizy, Jean Fermin, Vanessa Friedman, Michael Gorchov, Adam Green, Philip Horne, Philip Hughes, Nico Israel, Damian Lanigan, Darian Leader, Simon Page, Oliver Phillips, Michael Rips, Colin Robinson, Leon Klugman and the Singer family, Grub Smith, David Stewart, Philip Warnett, Arnold Weinstein, Jos Williams. Ann, David and Elizabeth ONeill have been a great help to me, and I am deeply indebted to the chambers of Mark Strachan Q.C. for its good-humoured assent to my lengthy sabbaticals. I wish to thank Neil Belton for his important editorial contribution, Rea Hederman for publishing this book in the United States, and Gill Coleridge for her steadfast encouragement and guidance over many years. My parents, Kevin ONeill and Caroline ONeill-Dakad, have, more than ever, been a vital source of encouragement, inspiration and advice; and so, too, my wife, Sally Singer. This book was her idea.

Preface to the Vintage Edition

Some day we shall get up before the dawn

And find our ancient hounds before the door,

And wide awake know that the hunt is on;

Stumbling upon the blood-dark track once more,

That stumbling to the kill beside the shore

W. B. Yeats, Hound Voice

Blood-Dark Track, published in 2001, describes the inquiry I undertook into the history of my family, Irish and Turkish, from 1995 to 2000. The inquiry was propelled by my curiosity about the unexplained incarcerations of both my grandfathers during the Second World War, a private oddity that, looked into, gave entry to obscure, sometimes frightful parishes of Irish and Middle Eastern history. These places had an essentially, or especially, imaginary quality to a visitor from my situation, which is to say, a Westerner at the twentieth centurys end whose freedom from geopolitical upheaval and its connected dangers and responsibilities seemed as complete as possible. We know what happened next.

As its text makes clear, Blood-Dark Track was written by a practicing lawyer. My work as a London barrister came to an indefinite end by 2001, by which time I had lived in the United States for about three years. I was in New York City on September 11th, 2001. That day and its consequences made up an ingredient of the book I wrote after Blood-Dark Track, a work of fiction titled Netherland and identified by some as a 9/11 novel. I have no quarrel with this tag, even assuming that I have a quarrelers standing, which is doubtful. But I will allow myself to state that, if I have written a 9/11 book, that book would, in my mind, be Blood-Dark Track.

This edition is dedicated to the memory of my beloved grandmother, Eileen ONeill.

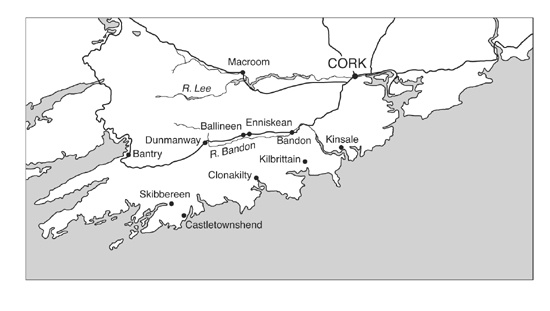

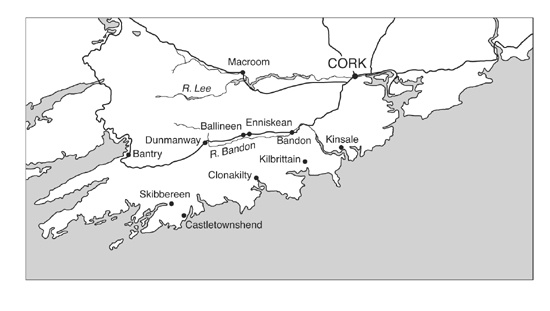

West Cork

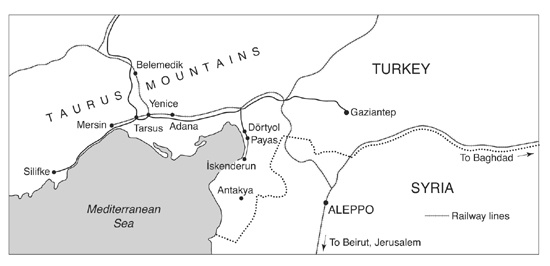

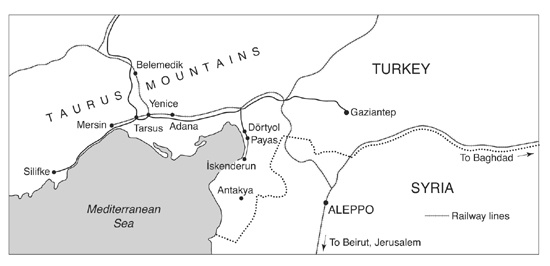

Turkey/Syrian border, Spring 1942

For me it began in far-off Mesopotamia now called Iraq, that land of Biblical names and history, of vast deserts and date groves, scorching suns and hot winds, the land of Babylon, Baghdad and the Garden of Eden, where the rushing Euphrates and the mighty Tigris converge and flow down into the Persian Gulf.

It was there in that land of the Arabs, then a battle-ground for the contending Imperialistic armies of Britain and Turkey, that I awoke to the echoes of guns being fired in the capital of my own country, Ireland.

Tom Barry, Guerrilla Days in Ireland

At some point in my childhood, perhaps when I was aged ten, or eleven, I became aware that during the Second World War my Turkish grandfather my mothers father, Joseph Dakad had been imprisoned by the British in Palestine, a place exotically absent from any atlas. A shiver of an explanation accompanied this information: the detention had something to do with spying for the Germans. At around the same age, I also learned that my Irish grandfather, James ONeill, had been jailed by the authorities in Ireland in the course of the same war. Nobody explained precisely why, or where, or for how long, and I attributed his incarceration to the circumstances of a bygone Ireland and a bygone IRA. These matters went largely unmentioned, and certainly undiscussed, by my parents in the two decades that followed. Indeed, the subject of my late grandfathers was barely raised at all and, save for a wedding-day picture of Joseph and his wife, Georgette, there were no photographs of them displayed in our home. Dwelling in the jurisdiction of parental silence, my grandfathers remained mute and out of mind.

Partially as a consequence of this, it was not until I was thirty that the curious parallelism in my grandfathers lives struck me with any force and that I was driven to explore it, to fiddle at doors that had remained unopened, perhaps even locked, for so many years; and not until then that I began to make out what connected these two men, who never met, and these two captivities one in the Levant heat, the other in the rainy, sporadically incandescent plains of central Ireland.