J. Powers - Wheat That Springeth Green

Here you can read online J. Powers - Wheat That Springeth Green full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2000, publisher: NYRB Classics, genre: Prose. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Wheat That Springeth Green: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Wheat That Springeth Green" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Wheat That Springeth Green — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Wheat That Springeth Green" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

J. F. Powers

Wheat That Springeth Green

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

J.F. POWERS (19171999) was born in Jacksonville, Illinois and studied at Northwestern University while holding a variety of jobs in Chicago and working on his writing. He published his first stories in The Catholic Worker and, as a pacifist, spent thirteen months in prison during World War II. Powers was the author of three collections of short stories and two novelsMorte DUrban, which won the National Book Award, and Wheat That Springeth Greenall of which have been reissued by New York Review Books. He lived in Ireland and the United States and taught for many years at St Johns University in Collegeville, Minnesota.

KATHERINE A. POWERSs column on books and writers ran for many years in The Boston Globe and now appears in The Barnes & Noble Review under the title A Reading Life. She is the editor of Suitable Accommodations: An Autobiographical Story of Family Life The Letters of J. F. Powers, 19421963, forthcoming in 2013.

~ ~ ~

INTRODUCTION

I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift. .

ECCLESIASTES, IX, 11THE ORIGINAL TITLE given by my father to this, his second and final novel a work that took almost twenty-five years to finish was The Sack Race. It was called that in the ancient contract he signed with Knopf and in notes and story lines and countless manuscript versions. Though dropped from the title, a sack race remains a pivotal event in the book and serves, too, as a metaphor for the priesthood. In the novel, as in Ecclesiastes, the race does not go to the swift, while much of the action does indeed take place under the sunthe sweat and heat of summer being synonymous with the human condition in my fathers mind.

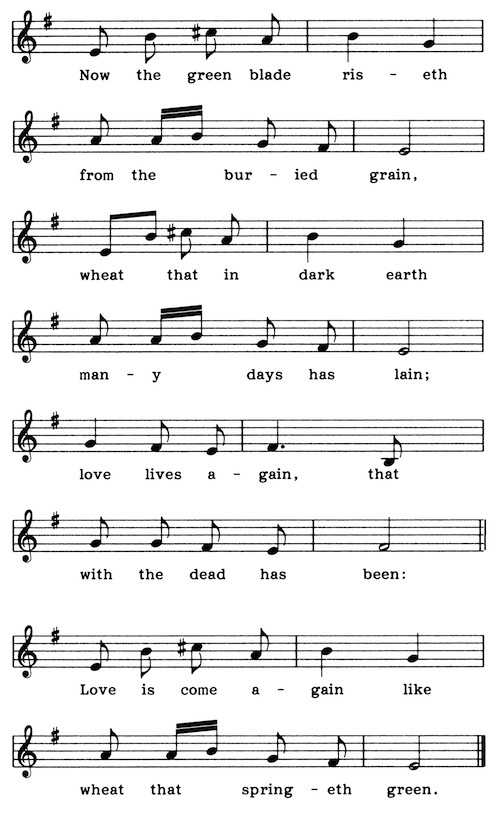

It was in reference to The Sack Race that, year after year, this master of the art of tinkering and procrastination wrote a penitential letter of regret to Robert Gottlieb, his editor at Knopf. (He kept the folded drafts of these annual notes clipped together in his desk drawer as a scourge.) At some point, though, out of this great weight of paper, time, and inertia, the book was born again as Wheat That Springeth Green.

He found the phrase the title and last line of a medieval carol while paging through a hymnal and was struck by the rightness of the words. The hymns message, too, was a powerful antidote to despondency. In the years he was working on the novel, he passed from being a middle-aged man with bright prospects to one of threescore and ten; and while, perversely, he found it inconceivable that he himself would die, he marked the death of his mother and his father, and witnessed the dying torments of his wife. These events shocked him to the core.

Written over an increasingly dark time, Wheat That Springeth Green was shaped by my fathers growing conviction of the progressive and irredeemable absurdity of things. He was a connoisseur of the dull, the mediocre and the second-rate, and of the disingenuous and fraudulent, but now it seemed that their dominion was truly come. Stupidity, obliviousness, and credulousness had taken over. The quality of food, drink, tobacco, transportation, conversation, religious practice, and art was in sharp decline. And people die: they just check out, are gone, leaving a whole bunch of junk behind.

Yet, in spite of everything, he did not despair. He possessed what G.K. Chesterton called Christian optimism, a paradoxical optimism based on the fact that we do not fit in the world, that every awful thing, every dismal victory of the moronic and specious, is just another confirmation that what happens under the sun is not reality, that we have here, as he took satisfaction in saying, no lasting home. In a contrarian assertion of hope, he transformed the dreck of modern existence, in which we are all bogged down, into a medium out of which springs beauty and new life. This is the view projected in Wheat That Springeth Green: As for feeling thwarted and useless, Joe, the novels uncomfortable hero, reflects, he knew what it meant. It meant that he was in touch with reality.

The sense that the world is an alien place of arbitrary arrangements is far more pronounced in Wheat That Springeth Green than in my fathers earlier novel, Morte DUrban. The author of that book, unlike the man who finally finished Wheat, believed that while the world was not the last stop in the journey, it did have something to offer. The via delicata traveled by Urban before he is cast into the wilderness is an enchanted arena of aged steaks and vintage wines, sleek cars, expense accounts, and manly bonhomie. Its a dangerous place, certainly, for just as the priest must be particular in his dress and demeanor, so must he not connive at the sins of those who pay his way. But the prudent man can avoid the devils snares; for him the real trap is the schemes sprung from second-rate minds. This, at least, is the view taken by the unredeemed Urban, a view that my father appreciated not only for its competence and discrimination but for its faint air of roguishness. But, of course, it would not do in the end. His hero is finally driven to recognize that he is no mere man of the world, that his business is not business, and he, like Sir Lancelot, lays aside his sword and becomes a priest.

In Wheat That Springeth Green, we see things through Joe Hacketts eyes, first as a child and later as the priest he becomes. Unlike Urban, Joe is seldom at ease, always a bit out of place, and forever trying to figure out whats going onreally going on as if with the aid of a manual. Whats wrong with this picture? Joe asks himself after a little gathering he has planned at his rectory fizzles out and he has been abandoned to watch the baseball game on TV alone. Nothing really, he told himself. The curate was entertaining in his room so as not to interfere with the game, the visiting priest was a fair-weather fan, if that, and so, really, nothing was wrong it meant nothing, nothing personal that the pastor sat alone. He didnt like it though.

If Morte DUrban presents the world as temptation, Wheat That Springeth Green presents rejection of the world as pretty tempting too. Urban is worldly; Joe wants to be otherworldly. As a seminarian and young priest, he affects the life of a contemplative. Hes a bit of a fanatic, in fact. But he cannot ignore the conditions around him. Cleanliness matters a little more to him than godliness, while heat an almost constant presence exacerbates the problem of dealing with other people. Heat, people; heat and people: Joe resorts to drink as a way of bearing up under both.

The set-up at the rectory at Joes first assignment is emblematic of the state of the world. There life is lived under the sway of Mrs Cox, the last in my fathers line of formidable housekeepers. Her dog attacks the priests ankles; her TV, running loud and long, is an obnoxious presence. Why is it so? Joes epiphany comes when he spots the horny, prayer-scarred knees and dog-bitten ankles of the pastor, Fr Van Slaag. He realizes that the old man is using Mrs Cox and her dog as crosses, as a means of sanctification and salvation making life make sense, which it otherwise wouldnt.

My father was drawn to priests as a subject because their lives are rich in anomaly, in the tensions and contradictions between earthly and spiritual goals that make moral scrutiny interesting. Time-serving, empire-building, reforming, all take on further moral complexity in the context of the priesthood. Beyond that, though, the predicament of the priest had a gruesome and particular fascination for him. To many young men of his generation, the problem of a religious vocation boiled down to what one would have to give up in order to assume what was, after all, a good place in this world not to mention excellent chances for a better one in the next. But to a man like my father, the real problem seemed less giving things up than taking them on: taking on people, specifically.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Wheat That Springeth Green»

Look at similar books to Wheat That Springeth Green. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Wheat That Springeth Green and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.