Jeffery Renard Allen

Song of the Shank

for Zawadi,

my wife, heart and gift, gift and heart

Traveling Underground (1866)

Light is the exception.

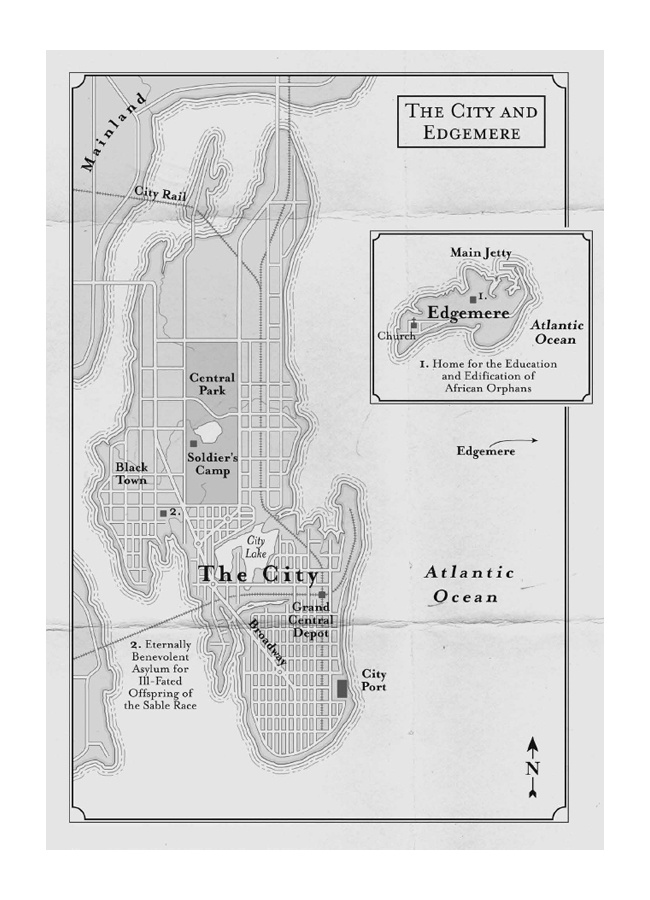

SHE COMES OUT OF THE HOUSE AND SEES FRESH SHAPES IN the grass, a geometrical warning she does not understand. Blades mashed down under a foot, half-digested clots of earth where shoe heels have bitten in, mutilated worms spiking up through regurgitated blackness piecemeal configurations, suggesting a mans shoe, two, large, like Toms but not Toms since Tom never wears shoes in the country. A clear track, left foot and right, running the circumference of the house, evidence that someone has been spying through the windows, trespassing at the doors. Had she been back in the city, the idea would already have occurred to her that the journalists were to blame, those men of paper determined in their unstoppable quest to unearth the long lost three years? four? Blind TomHalf Man, Half Amazingto reproduce the person, return him to public consumption, his name new again, a photograph (ideally) to go along with it, the shutter snapping (a thousand words). She has grown accustomed to such intrusion, knows how to navigate around pointed questions and accusations. (Ignore the bell. Deny any insistent knock on the door and that voice on the other side, tongue and fist filled with demands. Speak calmly through the wood, polite but brief. Use any excuse to thwart their facts and assumptions. No matter what, dont open the door.) Yet no one has called upon them their entire summer here in the country, those many months up until now, summers end. This can only mean that the journalists have changed their strategy, resorted to underhanded tactics and methods, sly games, snooping and spying, hoping to catch Tom (her) out in the open, guard down, unaware, a thought that eases her worry some until it strikes her that no newspaperman has ever come here before in all the years four? five? that theyve had this summer home. Alarm breaks the surface of her body, astonished late afternoon skin, all the muscles waking up. Where is Tom? Someone has stolen him, taken him away from her at last. She calls out to him. Tom! Her voice trails off. She stands there, all eyes, peering into the distance, the limb-laced edge of the afternoon, seeing nothing except Nature, untamed land without visible limits. The sky arches cleanly overhead, day pouring out in brightness across the lawn, this glittering world, glareless comfort in the sole circle of shade formed by her straw hat. Tom! She turns left, right, her neck at all angles. The house pleasantly still behind her, tall (two stories and an attic) and white, long and wide, a structure that seems neither exalted nor neglected, cheerful disregard, its sun-beaten dolls house gable and clear-cut timber boards long in need of a thick coat of wash, the veranda sunken forward like an open jaw, the stairs a stripped and worn tongue. Nevertheless, a (summer) home. To hold her and Tom. It stands isolate in a clearing surrounded by hundreds of acres of woods. Taken altogether it promises plenty, luxury without pretense, prominence without arrogance, privacy and isolation. Inviting. Homey. Lace curtains blowing in at the windows, white tears draining back into a face. The trees accept the invitation. Take two steps forward, light sparkling on every leaf. The nearest a dozen yards, a distance she knows by heart. Deep green with elusive shadings. Green holding her gaze. Green masking possible intruders (thieves). She must move, have a look around. No way out of it. Takes up a stout branch and holds it in front of her in defense, uselessly fierce. Even with her makeshift weapon she doubts her own capacities. Look at her tiny hands, her small frame, the heavy upholstery of her dress. But the light changes, seems to bend to the will of her instincts, lessening in intensity. (Swears she hears it buzz and snap.) She starts out through the grass Tom keeps the lawn low and neat, never permitting the grass to rise higher than the ankles her feet unexpectedly alert and flexible across the soft ground under her stabbing heels, no earthly sense of body. Winded and dizzy, she finds herself right in the middle of the oval turnaround between the house and the long macadam road that divides the lawn. Charming really, her effort, she thinks. In her search just now had she even ventured as far as the straggly bushes, let alone into the woods? It is later than she realized, darkness slowly advancing through the trees, red light hemorrhaging out, a gentle radiance reddening her hair and hands. Still enough illumination for a more thorough search. No timepiece on her person her heavy silver watch left behind on the bedroom bureau but shes certain that its already well past Toms customary hour of return, sundown, when Tom grows hurried and fearful, quick to make it indoors, as if he knows that the encroaching dark seeks to swallow him up, dark skin, dark eyes.

Had she missed the signs earlier? What has she done the entire day other than get some shut-eye? (A catalog of absent hours.) Imagine a woman of a mere twenty-five years sleeping the day away. (She is the oldest twenty-five-year-old in the world.) After Tom quit the house, she spent the morning putting away the breakfast dishes, gathering up this and that, packing luggage, orbiting through a single constellation of activities labor sets its own schedule and pace only to return to her room and seat herself on the bed, shod feet planted against the floor, palms folded over knees, watching the minute lines of green veins flowing along the back of her hands, Eliza contemplating what else she might do about the estate, lost in meditation so that she would not have to think about returning to the city, a longing and a fear. She dreaded telling Tom that this would be their last week in the country but knowing from experience that she must tell him, slow and somber, letting the words take, upon his return to the house for lunch; only fair that she give him a full week to digest the news, vent his feelings in whatever shape and form and yield.

It takes considerable focus for her to summon up sufficient will and guilt to start out on a second search. Where should she begin? A thousand acres or more. Why not examine the adjoining structures a toolshed, outhouse, and smokehouse lingering like afterthoughts behind the house, and a barn that looks exactly like the house, only in miniature, like some architects model, early draft. She comes around the barn the horse breathing behind the stall in hay-filled darkness, like a nervous actor waiting to take the stage dress hem swaying against her ankles, only to realize that she has lost her straw hat. A brief survey pinpoints it a good distance away, nesting in a ten-foot-high branch. She starts for it how will she reach that high? when she feels a hand suddenly on her shoulder, Toms warm hand Miss Eliza? turning her back toward the house, erasing (marking?) her body, her skin unnaturally pale despite a summer of steady exposure, his the darkest of browns. (His skin has a deeper appetite for light than most.) He has been having his fun with her, playing possum he moves from tree to tree his lips quivering with excitement, smiling white teeth popping out of pink mouth. Tom easy to spot really, rising well over six feet, his bulky torso looming insect-like, out of proportion to his head, arms, and legs what the three years absence from the stage has given him: weight; each month brings five pounds here, another five pounds there, symmetrical growth; somewhere the remembered slim figure of a boy now locked inside this seventeen-year-old (her estimation) portly body of a man his clothes shoddy after hours of roughing it in the country an agent of Nature his white shirt green- and brown-smeared with bark and leaf stains.