This edition first published in the United States in 2009 by

Overlook Duckworth Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

New York & London

NEW YORK:

The Overlook Press

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

[for individual orders, bulk and special sales, contact sales@overlookny.com]

LONDON:

Duckworth

90-93 Cowcross Street

London EC1M 6BF

inquiries@duckworth-publishers.co.uk

www.ducknet.co.uk

Copyright 2009 by Deirdre OConnell

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission lin writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-4683-0595-1

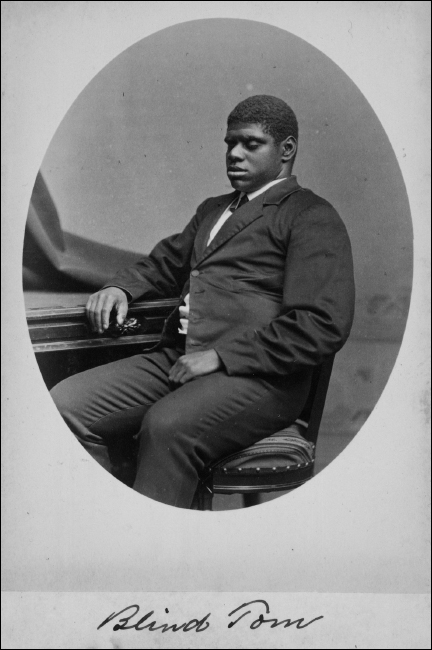

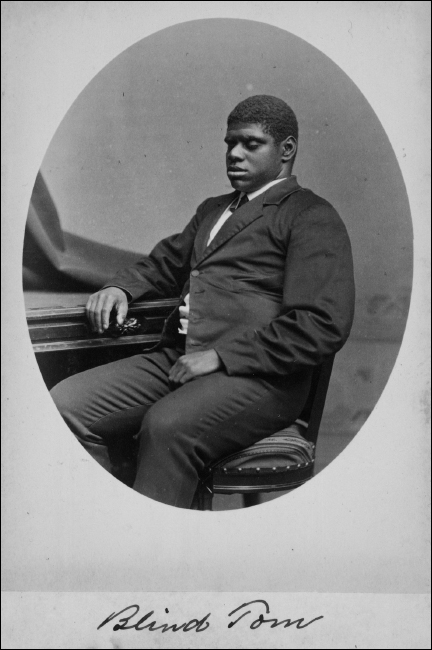

Blind Tom in 1882

To Jasmine, Indigo and David

Blind Toms concert program, which contains a biographical note that is the source of as many fictions as facts.

W HEN The New York Times REPORTED B LIND T OMS DEMISE IN H OBOKEN , New Jersey in 1908, it was the fourth time in twenty years his death had been announced. And still the mourners at his funeral werent convinced it was the right man. The piano virtuoso had been entertaining the American public with his dazzling feats of mimicry and memory since the Civil War after all, and the body in the coffin seemed too young.

But as the wheezy melodeon ground out a tortured Nearer My God To Thee opinion suddenly shifted Toms way. A deafening clap of thunder drowned out the tormented hymn. The skies broke open and a glorious tempest whipped the trees in the chapel yard, their branches clattering the stain glass windows. A thunderstorm requiem, The Times reporter noted, to befit the genius of a composer whose music echoed natures rattle and hum. What the reporter did not realize was that this was not an isolated incident, but rather the final act of a life-long conversation between Tom and the natural world.

For years after Toms death, at least three or four Blind Toms were doing the rounds in dime circus freak shows across the country. Stumbling towards the piano, eyes rolled back, tongue lolling, arms outstretched like a hulking bearonly to utterly transform the moment their fingers touched the ivory. A divine ravishment flowing through their fingers, the music rising in heavenly tones (if the piano was in tune). He was a freak too good to leave mouldering in an unmarked grave. As the years passed and the last of the Tin Pan Alley generation followed the Civil Wars into eternity, all that remained of this man who never forgot was a scattered collection of memories. Fragments. Time erases us all and Blind Tom was hovering on the cusp of oblivion.

I first came across one such fragment during a visit home to Sydney, Australia in 1993 (I was then living in London) when a friend, artist Martin Sharp, showed me an entry in his 1920 edition of The Encyclopedia of Aberrations. The entry was Moronic Genius and detailed the phenomenal musical memory of Thomas Wiggins, a Georgia-born slave who assigned to his curious memory the music, sounds and voices of this turbulent time. Concertos, spirituals, sentimental ballads. Thunderstorms, weaponry, trains. Conversations, sermons, political speeches. He repeated everything just as he heard it, replete with hand gestures and poisebut only a superficial understanding of the impact slavery, abolition and secession had on him.

Martin asked me to look up Blind Tom in The British Library when I returned to London. I did, unearthing an 1868 concert program that compared his genius to Mozarts along with a handful of less-than-impressed concert reviews. Somewhere between maestro and charlatan, idiot and genius, was the real Blind Tom.

Six months later, chance brought a holiday to Washington, D.C. and after a quick nose through the index at the Library of Congress, I was lost to Blind Tom. Here, I discovered a mine of information, including Dr. Geneva Handy Southalls pioneering thesis. What emerged was not just a snapshot of Tom, but an all too disturbing picture of his masters and guardians desperately plotting ways to hold onto their Golden Goose.

A career in chains? Perhaps. Once Toms master discovered that the worthless runt he had purchased out of pity was a musical prodigy, he lost no time in licensing the eight-year-old to a Barnum-style showman, under whom Tom raised thousands of dollars for the Confederate War effort. Emancipation failed to deliver Tom from the shackles of slavery, his masters son merely morphing into the role of guardian and manager. Legally adjudged insane, Tom spent much of his life in perpetual motion, performing to packed houses across the continentthe profits of which financed his guardians extravagant lifestyle.

Back in London I set to work writingwhat? A biography, novel, documentary? What was the right format to fit this mixed bag of tour dates, concert reviews, lawsuits and judgments; this social history of slavery, war, emancipation? Why did it seem like I was retelling the history of nineteenth century America? Slowly the true nature of the problem dawned on me. My manuscript was more concerned with the people around Tom than Tom himself. The pages I was filling dealt with other peoples stories as if Tom was a bit player in his own life. I still did not understand my subject; had not yet come to grips with the enigma of Blind Tom.

Determined to crack this nut, I headed to the United States for an unofficial sabbatical in the countrys vast public libraries, colleges and archives and dug up a mountain of material, much of it bearing the stamp of two factually erratic articles that had been endlessly reworked and repeated over the century. Yet hidden amongst the repeats were some highly prized originals: a wonderfully candid and eclectic collection of eyewitness accounts.

Scores of people, from Toms masters grandson to Mark Twain, to soldiers, schoolteachers, booking agents and musicians had at some point written to magazines and journals describing their encounters with him. In the 1950s two writers attempted to publish books on him. I stumbled across both their research boxes, each holding even more first-hand accounts. Case studies written by psychologists, phrenologists and music professors all fleshed out, in striking detail, a picture of Tomnot the prodigy or the legendbut the man.

I learnt, for instance, that when Tom wasnt playing the piano he leaned his body forward, balanced on one leg and jumpedhuge gravity-defying leaps that no one could explain or commercially exploit. When Tom traveled by train he hissed, clattered and whistled along in unison, his entire body transformed by the locomotive. When alone, he entertained imaginary charactersserving them tea and swapping the days news. That in his hometown of Columbus, Georgia, folks believed that during the Firemans Parade the spirit of the drum entered Toms mothers ecstatic body and marked the unborn baby inside. Priceless glimpses and tidbits that confirmed to me that Tom was truly one in a hundred million.