Table of Contents

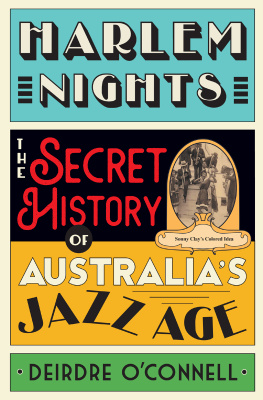

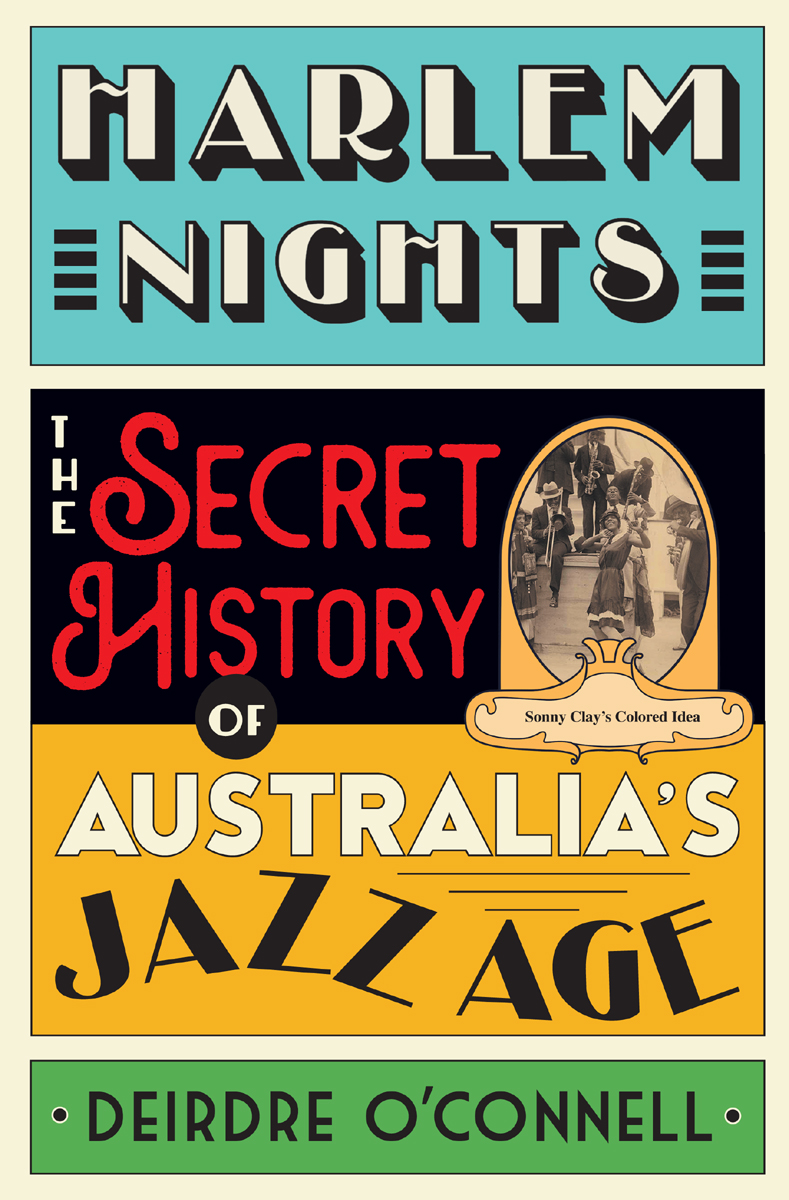

HARLEM NIGHTS

HARLEM NIGHTS

THE SECRET HISTORY OF AUSTRALIAS JAZZ AGE

DEIRDRE OCONNELL

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2021

Text Deirdre OConnell, 2021

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2021

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following story may contain images of deceased persons.

Front cover image: Sonny Clays Colored Idea arrive at Sydney Circular Quay, 19 January 1928. (Sam Hood Collection, State Library of NSW.) Back cover image: Sam Hood photographs the Sonny Clays Colored Idea performance of the Australian Stomp, 20 January 1928. (Sam Hood Collection, State Library of NSW.)

Cover design by Design by Committee

Text design and typesetting by Cannon Typesetting

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

9780522877649 (paperback)

9780522877656 (ebook)

CONTENTS

Sonny Clays Colored Idea arrive at Sydney Circular Quay, 19 January 1928. (Sam Hood Collection, State Library of NSW)

PROLOGUE

THE FRAME-UP

T his is the story of an Australian political conspiracy. Not the kind that faked the moon landing or concealed alien life, but a secret plan designed to limit individual freedom, consolidate power and engineer social change.

The year was 1928. It was a time of technological wonder and flux, when people sensed a world growing smaller and turning faster, and time speeding up. When efficiency was glorified and its lolling, time-wasting twin derided and scorned. In homes, factories and offices, American gadgetry was transforming Australian lives, saving minutes, even hours. The citizenry expended the surplus on a new category of time a Puritan once called idleness and advertisers labelled leisure.

In this new world, the single working girl made herself modern. Dance halls, moving picture houses, magazines, the wireless and gramophones opened gateways to the globe. Department stores stocked affordable copies of Paris fashions: fox stoles, Mary Jane shoes and skintight geometric knitwear. Hollywood vamps and ingenues narrated the pleasures and perils of Manhattans glamour and sophistication. Eye-rolling flappers telegraphed the allure of mascara, kohl and shingled hair. The fetish of the age, the female leg, specifically the knock-kneed or kicking dancing leg, was of more uncertain originsalthough persistent allusions to jungle rhythms pointed to other, and othered, worlds.

To a generation of leisured Australians, this looked and felt like Progress. But to committees of concerned citizens, policymakers and advisors, it smacked of Degeneration.

The dizzying speed of the modern world portended spiritual exhaustion, warned moral reformers and gatekeepers. Modern debauchery empowered inferior people who were weakening the human stock. Jazz violated the laws of harmony and tipped the world into chaos and confusion.

The rising tide of Black and Brown people and Negrification of American popular culture imperilled the supremacy of the British race.

To these many anxieties, one disgruntled former prime minister offered a simple, catch-all solution: racial purity.

We are a white island in a vast coloured ocean, proclaimed William Morris Hughes in the year of this particular political conspiracy. If we are not to be submerged, we must build dykes through which the merest trickle of the sea of colour cannot find its way.

When Billy Hughes wrote these words, Australia had never been so White, or so British, the result of a hard-line immigration policy that had deported thousands of Pacific Islanders and refused entry to all but a handful of Chinese migrants and other people of colour. Still, the former leader fumed: outraged that his party, the Nationalist Party, had gone soft on White Australia (and insulted that he was now a lowly backbencher, the victim of cold political expediency). The dykes he envisaged were all-encompassing in scaleand the rewards might even include his return from the political grave.

In so many nebulous ways, Billy Hughes was the spiritual godfather of the chain of events that was about to unfold, a master orator spinning a seductive vision of an all-White modern Australia.

Of course, he did not administer the conspiracy. That role fell to Major Longfield Lloyd, the New South Wales director of the domestic intelligence-gathering bureau, the Commonwealth Investigation Branch. Major Lloyds experience in dyke-building dated back to Billy Hughes internment policies of the Great War and purge of enemy aliens. Indeed, Lloyds swift progression through the ranks of military intelligence was hastened by the patronage of his friend and mentor.

In 1927, Major Lloyd had overseen the deportation of a knot of Black American boxers, one of whom was married with a child to a White Sydney woman. Yet the dyke continued to leak. From the pages of the daily press, the bold typeface of Tivoli Theatre advertisements announced the imminent arrival of a Black American jazz revue, Sonny Clays Colored Idea, the first to reach Australia: 25 Negro stars. 100 wonder minutes. Something New in Entertainment: Real Syncopation and Real Symphony.

As bandleader Sonny Clay later told it, the frame-up began with a sinister message tapped through to the SS Sierra the day the steamer came into radio contact with Sydney. On board were Harry Muller, the Tivoli Theatres West Coast agent and seventeen members of the Colored Idea, the all-Black jazz revue pieced together by Muller.

They were a remarkable bunch of dancers, comedians, vocalists and musicians. Whirlwind stepper Willie Covan first choreographed the Charleston on the Harlem stage. Nini Coycault was a Louisiana trumpet master of weavy patterns and shivery stuff. Cabaret singer Ivy Anderson could bring an audience to tears then wow them with a mad shuffle. She would soon shoot to fame with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. And, of course, 28-year-old Sonny Clay, the lanky, baby-faced bandleader was on the upward curve of a meteoric career. Five years earlier, he was playing fill-in spots in Tijuana jive joints. The week before he left California for Australia, the marquee lights outside Hollywoods favourite Harlem nightclub, the Plantation Caf, spelt his name. Inside, starlets waved to him from the dance floor. Big-name stars thanked him with hundred-dollar tips and bootleg liquor.