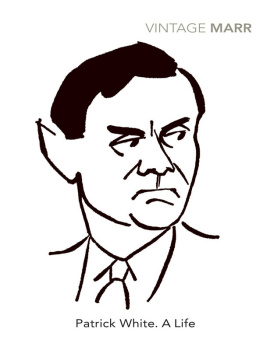

Patrick White

The Eye of the Storm

Patrick White was born in England in 1912. He was taken to Australia (where his father owned a sheep farm) when he was six months old, but educated in England, at Cheltenham College and Kings College, Cambridge. He settled in London, where he wrote several unpublished novels, then served in the RAF during the Second World War. He returned after the war to Australia, where he became the most considerable figure in modern Australian literature before being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1973. His position as a man of letters was controversial, provoked by his unpredictable public statements and his belief that it is eccentric individuals who offer the only hope of salvation. Technically brilliant, he is a modern novelist of whom the epithet visionary can safely be applied. Patrick White died in September 1990. In 2012, Knopf will publish The Hanging Garden. Handwritten in 1982 it had remained untranscribed, until now.

I was given by chance this human body so

difficult to wear.

N play

playHe felt what could have been a tremor of

heavens own perverse love.

Kawabata

Men and boughs break;

Praise life while you walk and wake;

It is only lent.

David Campbell

THE OLD womans head was barely fretting against the pillow. She could have moaned slightly.

What is it? asked the nurse, advancing on her out of the shadow. Arent you comfortable, Mrs Hunter?

Not at all. Im lying on corks. Theyre hurting me.

The nurse smoothed the kidney-blanket, the macintosh, and stretched the sheet. She worked with an air which was not quite professional detachment, nor yet human tenderness; she was probably something of a ritualist. There was no need to switch on a lamp: a white light had begun spilling through the open window; there was a bloom of moonstones on the dark grove of furniture.

Oh dear, will it never be morning? Mrs Hunter got her head as well as she could out of the steamy pillows.

It is, said the nurse; cant you cant you feel it? While working around this almost chrysalis in her charge, her veil had grown transparent; on the other hand, the wings of her hair, escaping from beneath the lawn, could not have looked a more solid black.

Yes. I can feel it. It is morning. The old creature sighed; then the lips, the pale gums opened in the smile of a giant baby. Which one are you? she asked.

De Santis. But Im sure you know. Im the night nurse.

Yes. Of course.

Sister de Santis had taken the pillows and was shaking them up, all but one; in spite of this continued support, Mrs Hunter looked pretty flat.

I do hope its going to be one of my good days, she said. I do want to sound intelligent. And look presentable.

You will if you want to. Sister de Santis replaced the pillows. Ive never known you not rise to an occasion.

My will is sometimes rusty.

Dr Gidleys coming in case. I rang him last night. We must remember to tell Sister Badgery.

The will doesnt depend on doctors.

Though she might have been in agreement, it was one of the remarks Sister de Santis chose not to hear. Are you comfortable now, Mrs Hunter?

The old head lay looking almost embalmed against the perfect structure of pillows; below the chin a straight line of sheet was pinning the body to the bed. I havent felt comfortable for years. said the voice. And why do you have to go? Why must I have Badgery?

Because she takes over at morning.

A burst of pigeons wings was fired from somewhere in the garden below.

I hate Badgery.

You know you dont. Shes so kind.

She talks too much on and on about that husband. Shes too bossy.

Shes only practical. You have to be in the daytime. One reason why she herself preferred night duties.

I hate all those other women. Mrs Hunter had mustered her complete stubbornness this morning. Its only you I love, Sister de Santis. She directed at the nurse that milky stare which at times still seemed to unshutter glimpses of a terrifying mineral blue.

Sister de Santis began moving about the room with practised discretion.

At least I can see you this morning. Mrs Hunter announced. You cant escape me. You look like some kind of biglily.

The nurse could not prevent herself ducking her veil.

Are you listening to me?

Of course she was: these were the moments which refreshed them both.

I can see the window too, Mrs Hunter meandered. And something a sort of wateriness oh yes, the looking-glass. All good signs! This is one of the days when I can see better. I shall see them!

Yes. Youll see them. The nurse was arranging the hairbrushes; the ivory brushes with their true-lovers knots in gold and lapis lazuli had a fascination for her.

The worst thing about love between human beings, the voice was directed at her from the bed, when youre prepared to love them they dont want it; when they do, its you who cant bear the idea.

Youve got an exhausting day ahead, Sister de Santis warned; youd better not excite yourself.

Ive always excited myself if the opportunity arose. I cant stop now for anyone.

Again there was that moment of splintered sapphires, before the lids, dropping like scales, extinguished it.

Youre right, though. I shall need my strength. The voice began to wheedle. Wont you hold my hand a little, dear Mary isnt it? de Santis?

Sister de Santis hesitated enough to appease the spirit of her training. Then she drew up a little mahogany tabouret upholstered in a faded sage. She settled her opulent breasts, a surprise in an otherwise austere figure, and took the skin and bone of Mrs Hunters hand.

Thus placed they were exquisitely united. According to the light it was neither night nor day. They inhabited a world of trust, to which their bodies and minds were no more than entrance gates. Of course Sister de Santis could not answer truthfully for her patients mind: so old and erratic, often feeble since the stroke; but there were moments such as this when they seemed to reach a peculiar pitch of empathy. The nurse might have wished to remain clinging to their state of perfection if she had not evolved, in the course of her working life, a belief no, it was stronger: a religion of perpetual becoming. Because she was handsome in looks and her bearing suggested authority, those of her colleagues who detected in her something odd and reprehensible would not have dared call it religious; if they laughed at her, it was not to her face. Even so, it could have been the breath of scorn which had dictated her choice of the night hours in which to patrol the intenser world of her conviction, to practise not only the disciplines of her professed vocation, but the rituals of her secret faith.

Then why Mrs Hunter? those less dedicated or more rational might have suggested, and Mary de Santis failed to explain; except that this ruin of an over-indulged and beautiful youth, rustling with fretful spite when not bludgeoning with a brutality only old age is ingenious enough to use, was also a soul about to leave the body it had worn, and already able to emancipate itself so completely from human emotions, it became at times as redemptive as water, as clear as morning light.

This actual morning old Mrs Hunter opened her eyes and said to her nurse, Where are the dolls?

Where you left them, I expect, Because her inept answer satisfied neither of them, the nurse developed a pained look.

But thats what they always say! Why dont they bring them? Mrs Hunter protested.

play

play