Dawn Raffel

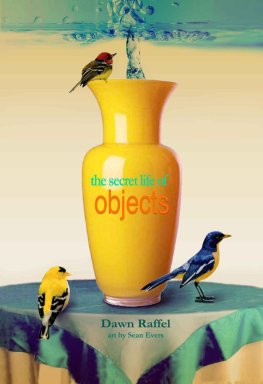

The Secret Life of Objects

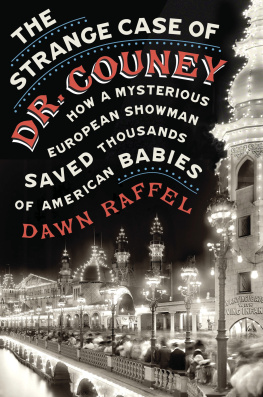

Dawn Raffel is the author of two story collections, Further Adventures in the Restless Universe and In the Year of Long Division, and a novel, Carrying the Body. Her fiction has appeared in O, The Oprah Magazine, BOMB, Conjunctions, The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories, The Quarterly, NOON, and many others. She has taught in the MFA program at Columbia University, and at Summer Literary Seminars in Montreal, Canada, and St. Petersburg, Russia. She is an editor at large for Readers Digest and the editor of The Literarian, the online journal for the Center for Fiction in New York City.

Praise for Dawn Raffels The Secret Life of Objects

Sometimes things shatter, Dawn Raffel writes in The Secret Life of Objects. More often they just fade. But in this evocative memoir, moments from the past do not fade they breathe on the page, rendering a striking portrait of a woman through her connections to the people shes loved, the places she been, whats been lost, and what remains. In clear, beautiful prose, Raffel reveals the haunting qualities of the objects we gather, as well as the sustaining and elusive nature of memory itself.

Samuel Ligon, author of Drift and Swerve: Stories

Dawn Raffel puts memories, people and secrets together like perfectly set gems in these shimmering stories, which are a delight to read. Every detail is exquisite, every character beautifully observed, and every object becomes sacred in her kind, capable hands. I savored every word.

Priscilla Warner, author of Learning to Breathe My Yearlong Quest to Bring Calm to My Life

Praise for Dawn Raffels Earlier Writing

Vanity Fair

The stories in Dawn Raffels astonishing Further Adventures in the Restless Universe (Dzanc) are as sharp and bright as stars.

Elissa Schappell

Time Out New York

Her prose is intense enough to make even everyday topics seem fire-hot.

The Daily Beast (5 Must-Read Story Collections)

The 21 stories in Raffels slim second collectionreflect the disconnects, interruptions, and riddles in a contemporary womans hectic life. The final story, Beyond All Blessing and Song, Praise and Consolation, titled for a line in the mourners Kaddish, distills sadness into an ending both poetic and pure.

Jane Ciabattari

O, The Oprah Magazine

Sharp, spare stories about women at, or approaching, the end of their ropes.

Sara Nelson

More Magazine

Highly imaginative stories filled with sly wit

Carmela Ciuraru

Publishers Weekly

Raffels stripped-to-the-bone prose is a model of economy and grace.

Booklist

These reflective, well-tempered fictions are bursting with energy, requiring readers to look more closely at the world around them.

Jonathan Fullmer

New Pages

Reality may be an adventure in Raffels cleverly and artfully crafted new collection, and as she writes it, is always an adventure worth taking.

Sara Rauch

American Book Review

The emphasis here must be on Raffels new contribution, worth celebrating whatever its category.

John Domini

The Secret Life of Objects

The following chapters were previous published as follows:

The Tea Set from Japan, The Prayer Book, The Brides Bible, The Teacup, The Florsheim Dog, Tranqil Ease, and Garnet Earrings in Willow Springs

The Lady on the Vase, The Lock, The Thing with Wings, My Grandmothers Recipes, and The Dress in The Brooklyn Rail

The Rocking Chair, The Glass Angel, The Rug, and The Mirror in The Milan Review

The Sewing Box and Rascal in Salt Hill

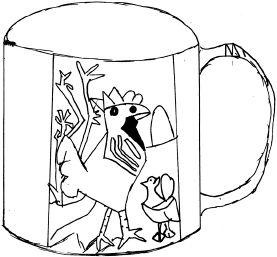

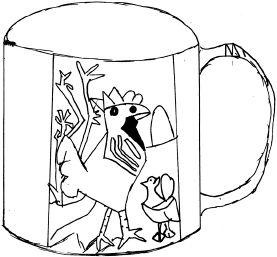

The Mug in Unsaid

The Cat in Moonshot

Yosemite and the Range of Light in Everyday Genius

The Watch in The Collagist

Medals (under the title As-Is) in Wigleaf

The Nesting Bowls (under the title Hungary) in The Lifted Brow (Australia)

The Moonstone Ring in Numro Cinq

The Secret Life of Objects

The mug came first: a clay-based receptacle for stimulant, for memory, for story, for tonic for aloneness.

Surveying my house I found myself surrounded by surfaces and vessels, by paper and glass, by cloth, wood, clay, paint, and also my late artist mothers renditions of things.

Already the contents are shifting shape. Already I cannot recall a voice, a year, the way the light fell speckled in a room.

Objects are intractable. We own them. We dont.

All memoir is fiction.

We try to fit the pieces together again.

Every morning I drink coffee out of a mug that I took from my mothers house. It is a blue mug from the Milwaukee Art Museum where my mother was a docent during the last years of her life. The image is of a Picasso, a bird.

My mothers death was sudden. It was my stepfather whod been dying, of stomach cancer, and whod begun home hospice care. My mother, whod been despondent (I was supposed to die first, she told me. This was not supposed to happen.), did not wake up one morning. The house was left in the way a house is left when someone leaves the world mid-thought. Nothing had been sorted or dispensed with or hidden, and after my stepfather died too, it fell to me to see to the houses contents.

My mother had saved everything. This was the good news and also the bad news. Because she had been an artist, her house was filled with dozens upon dozens of sculptures, in clay and in wood, paintings and drawings, in oil, in acrylic, in charcoal, in pencil, of water and trees and women so many women from so many angles, clothed, nude; their faces, their bodies, the suggestion of the inner life. Roses abounded. Shells, too, the pinkened insides of conches like portals to dreams. My sister and I could not take them all, and I didnt want them to sit in storage for 20 or 30 years until someone else threw them out. I found a taker for everything except the drawings, wisps of thought, which I tossed, reluctantly. My mothers favorite bench by the lake, the place where she went to cry after my father left, rendered in woodblock, went to a cousin; waters and skies to another cousin, to aunts and stepsiblings and in-laws and friends. I took home the roses she painted when she was young, and the sculpted likeness of the woman who was me, and the heads of women darkened with patina, the red clay torsos, the Renoir copy that had hung over the sofa, that my children wanted. I took the bronze dancer, a copy of a Degas we had seen the last time my mother had led my children and me through the museum, four months before she died.

Then I dispersed the glass paperweights my mother had collected, abstract worlds caught in globes, molten bubbles, veins of dye, nothing so overt as a scene. I gave away the tables and the chairs, their cushions stained; the beds, the lamps, the art supplies, some still untouched: brushes and gessoes and paints and craypas most to my sister, some to my younger son who went to art school papers and rags; four closets full of clothing, plus still more: old crinolines and plaids and silks and tablecloths folded over rusting metal hangers in the basement. I took the shoes nested in tissue in their cardboard boxes; they fit me exactly, vintage, scarcely worn. My mother and I had the same feet. Our faces were similar enough to startle her friends, though hers held a different expression a kind of openness that drew the attention of strangers. Our bodies were different hers voluptuous, mine diminutive. I took the smaller jewels, necklaces in boxes, in plastic bags, strewn; and earrings, pins, and loose beads.