Saadat Hasan Manto

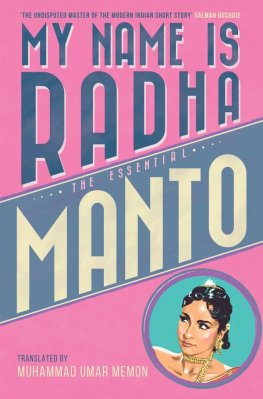

My Name Is Radha

The first edition of this book [Chughad] was published in Bombay. After Partition I handed over the manuscript to Book Publishers Limited and left for Pakistan. From here I wrote to Ali Sardar Jafri, who was then employed at Book Publishers, saying that the only way to hasten the publication of the book was for him to write the foreword and that I would accept whatever he said. He replied:

Of course, Ill write it with pleasure. However, the book doesnt need a foreword, much less one by me. You are well aware that our literary views are far apart. That aside, I regard you very highly and expect great things from you.

In that case, I wrote to Jafri Sahib, let the book go without a foreword. But by then, as became clear from his subsequent letter, he had already written a brief foreword and included it in the book. Regardless of its contents, it is there in the first edition of Chughad. However, Ive excised it from the present edition, not because I have, God forbid, developed a sudden enmity towards Jafri Sahib or started hating him, but in view of the absurd furore the so-called Progressives of Bombay have raised about my work lately, I didnt think it was proper to have their most active member become an appendix to my reactionary work.

I was still in Bombay when Bb Gpnth, one of the stories of this collection, appeared in the literary magazine Adab-e Latf. All the Progressives praised it to high heaven, even anointing it as the best short story of that year. Ali Sardar Jafri, Ismat Chughtai and Krishan Chandar especially applauded it. Krishan Chandar even gave it a prominent place in Hal k S,. Then, all of a sudden God knows what got into their heads every single Progressive turned against the storys greatness. First they faulted it in hushed voices and condemned it in whispers. But now every Progressive of India and Pakistan has begun running it down, openly and loudly, as reactionary, immoral, sordid and depraved.

The same treatment was meted out to another of my stories, Mr Nm Rdh Hai [My Name is Radha], though when it was first published the Progressives could not stop applauding it, beside themselves with enthusiasm and exhilaration. Anyway, when Ali Sardar Jafri penned his foreword as an offering to progressivism, he wrote to me:

I would like to know your opinion of my foreword. Ive written it with much sincerity and love, and Im now thinking of writing a longish article about your short stories. So far, run-of-the mill people have only reviled you. It is useless to expect anything better from them.

Dont these lines cry out to have every single word in them thrown in the face of all Progressives and let reactionism smile quietly? In the same letter, Ali Sardar went on to say: I consider your short story Khol-do [Open It!] a masterpiece of this period.

The tragedy that befell the Progressives, or perhaps this story, was its publication in Nuqsh (Lahore), under the editorship of His Honour Ahmad Nadim Qasimi the guru of Pakistani Progressives and the architect of the pithy zindag-moz-o-zindag-mez adabotherwise it too would have been consigned to the dustbin of non-literature, leaving me gawking at progressivisms red face.

The only reason my book Siyh Hshiye didnt go down well with the Progressives was that Muhammad Hasan Askari, whom theyd already put on their blacklist, had written its foreword. And so, with his characteristic sincerity and love, Ali Sardar Jafri again wrote to me:

What is this I hear from Lahore that Muhammad Hasan Askari is writing the foreword to some new book of yours? How on earth the two of you could hit it off baffles me. I dont consider Hasan Askari a sincere person at all.

One really must hand it to the Progressives for mounting such an efficient and speedy system of communication. News from here travels in the blink of an eye to Khetwadis Kremlin with total accuracy. What Ali Sardar Jafri had heard was absolutely correct. The end result was that Siyh Hshiye had hardly been out before it was condemned and trashed as a bunch of reactionary writing. It is amazing, though, that as Ali Sardar Jafri was drafting his preface for my Chughad, it never dawned on him that he and Manto were two mutually exclusive entities and that our literary views were, according to him, far apart. Alas, my Progressive friends are averse to thinking! They consider it a negative act.

Let me present an example of this aversion. The magazine Saver, a publication of Nay Idra, which is owned by Nazeer Ahmad Chaudhry, is the Mouthpiece of the Progressive Literary Movement. It has blacklisted me. In its pages Im routinely dubbed as reactionary, opportunistic, individualistic, hedonistic and escapist. And yet Nay Idra advertises one of my books in the following words:

Saadat Hasan Manto is the standard-bearer of truth. He is armed with the double-edged sword of truth, which he brandishes fearlessly in the thick forests of the government and society, tearing asunder all their veils of hypocrisy and affectation. Abuse is heaped on him, but he smiles. He marches down a path that he alone can travel, impervious to any thought of reward or punishment.

Did I smile on reading this advertisement in the pages of Saver? No, I laughed my head off. Forget the subliminal message, it will greatly help the readers, rather think: Arent the Progressives and their equally progressive publishers travelling along a path which they alone can travel, without caring a fig about their consciences? During the recent Bhopal Conference, Ismat Shahid Latif* valiantly, and at one go, openly disowned any of her stories that didnt measure up to the standard of progressivism. Why dont these progressive publishers take their cue from Ismats forthrightness? They should burn all the books by blacklisted reactionaries. And if they were to do so, I would surely kiss their hands.

Any literary work that aspires to the condition of art must forget politics, religion, and, ultimately, morals. Otherwise it will be a pamphlet, a sermon, or a morality play.

GUILLERMO CABRERA INFANTE

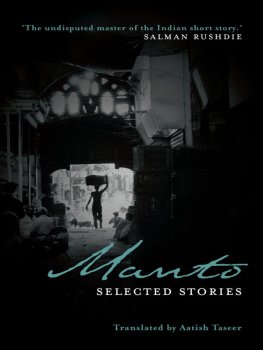

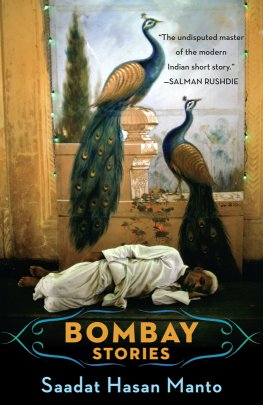

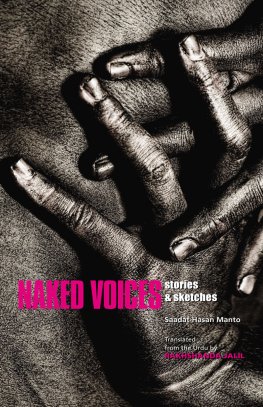

By common consensus of most Urdu critics and readers of fiction, Saadat Hasan Manto (191255) is unquestionably the pre-eminent Urdu short story writer of the first half of the previous century. And even now the popularity of this iconic writer has not waned. He is avidly read and admired across the South Asian subcontinent and is also well known overseas, thanks to the many translations of his choicest work into English and other European languages. A prolific writer and, in his early years, a translator and journalist, he managed to produce in his short life of only forty-three years an enormous literary corpus, mostly short stories, but also plays and works of non-fiction, collected in five fat tomes of roughly a thousand pages each an amazing testimony to the astonishing range of the authors thematic reach!

Born in Ludhiana in British India, Manto started work as a member of the editorial staff of Maswt, an Urdu daily published from his native Ludhiana. In 1936 he moved to Bombay to work as a scriptwriter for films before moving on to Delhi in 1941. Here, he joined the Urdu Service of All India Radio and wrote radio plays. The following year saw him back in Bombay, where he resumed his earlier work for the film industry.

With the political situation in Bombay deteriorating rapidly in the aftermath of Partition, and communal rioting having erupted across the country, Manto felt constrained to leave for Pakistan in 1948. The move does not appear to have been motivated by ideological reasons. In Bombay, Manto had enjoyed relative prosperity and at times even abundance. In Pakistan he was reduced to living in financial straits, made worse by his chronic dependence on alcohol, which led to cirrhosis of the liver that eventually claimed his life.