Carlos Fuentes

Terra Nostra

What does that old spook want?

Goya, Los caprichos

Fervid in her fetid rags. It is she, the first

False mother of many, like you, aggrieved

By her, and for her, grieving.

Cernuda, Ser de Sansuea

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born

Yeats, Easter, 1916

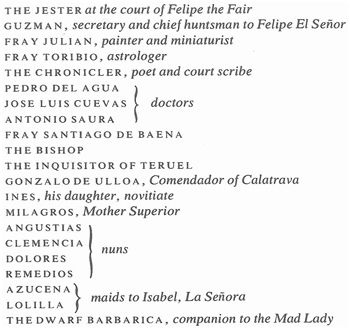

THE LORDS

FELIPE, the Fair, married to

JOANNA REGINA, the Mad Lady

FELIPE, El Seor, son and heir to the former, married to

ISABEL, La Seora (Elizabeth Tudor), his English cousin

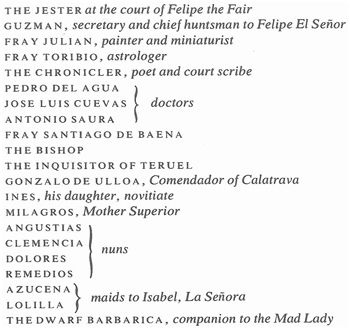

THE COURT

THE BASTARDS

THE PILGRIM, son of Felipe the Fair out of Celestina

DON JUAN, son of Felipe the Fair out of Isabel, La Seora

THE IDIOT PRINCE, son of Felipe the Fair out of a she-wolf

THE DREAMERS

LUDOVICO, student of theology

PEDRO, peasant and sailor

SIMON, monk

CELESTINA, peasant girl, witch, and procuress

MIHAIL-BEN-SAMA, wanderer

DON QUIXOTE DE LA MANCHA, knight-errant

SANCHO PANZA, his squire

THE WORKERS

JERONIMO, blacksmith and husband to Celestina

MARTIN, son of serfs from Navarre

NUO, son of a foot soldier of the Moorish frontier

CATILINON, rogue from the streets of Valladolid

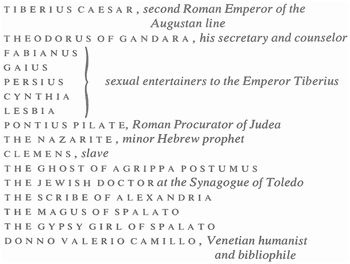

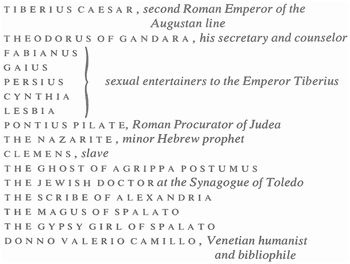

THE MEDITERRANEANS

THE FLEMISH

THE MISTRESS of the Beguine Monastery, Bruges

SCHWESTER KATREI, possessed Beghard

HIERONYMUS BOSCH, painter and adherent to the Adamite sect

THE DUKE OF BRABANT

THE INDIANS

THE LORD OF MEMORY

THE LADY OF THE BUTTERFLIES

THE FAT PRINCE

THE WHITE LORDS OF HELL

THE LORD OF THE GREAT VOICE

THE PARISIANS

POLLO PHOIBEE, sandwich man

CELESTINA, sidewalk painter

LUDOVICO, flagellant

SIMON, monk, leader of the penitents

MME ZAHARIA, concierge

RAPHAEL DE VALENTIN, man-about-town

VIOLETTA GAUTIER, consumptive courtesan

JAVERT, police inspector

JEAN VALJEAN, former convict

OLIVEIRA, Argentine exile

BUENDIA, Colombian colonel

SANTIAGO ZAVALITA, Peruvian journalist

ESTEBAN and SOFIA, Cuban cousins

HUMBERTO, deaf-and-dumb Chilean

CUBA VENEGAS, Cuban torch singer

THE VALKYRIE, Lithuanian benefactress

FLESH, SPHERES, GRAY EYES BESIDE THE SEINE

Incredible the first animal that dreamed of another animal. Monstrous the first vertebrate that succeeded in standing on two feet and thus spread terror among the beasts still normally and happily crawling close to the ground through the slime of creation. Astounding the first telephone call, the first boiling water, the first song, the first loincloth.

About four oclock in the morning one fourteenth of July, Pollo Phoibee, asleep in his high garret room, door and windows flung wide, dreamed these things, and prepared to answer them himself. But then he was visited in his dream by the somber, faceless figure of a monk who spoke for Pollo, continuing in words what had been an imagistic dream: But reason neither slow nor indolent tells us that merely with repetition the extraordinary becomes ordinary, and only briefly abandoned, what had once passed for a common and ordinary occurrence becomes a portent: crawling, sending carrier pigeons, eating raw deer meat, abandoning ones dead on the summits of temples so that vultures as they feed might perform their cleansing functions and fulfill the natural cycle.

Only thirty-three and a half days earlier the fact that the waters of the Seine were boiling could have been considered a calamitous miracle; now, a month later, no one even turned to look at the phenomenon. The proprietors of the black barges, surprised at first by the sudden ebullition, slammed against the walls of the channel, had abandoned their struggle against the inevitable. These men of the river pulled on their stocking caps, extinguished their black tobaccos, and climbed like lizards onto the quays; the skeletons of the barges had piled up beneath the ironic gaze of Henri de Navarre and there they remained, splendid ruins of charcoal, iron, and splintered wood.

But the gargoyles of Notre-Dame, knowing events only in the abstract, embraced with black stone eyes a much vaster panorama, and twelve million Parisians understood finally why these demons of yesteryear stick out their tongues at the city in such ferociously mocking grimaces. It was as if the motive for which they were originally sculptured was now revealed in scandalous actuality. It was clear the patient gargoyles had waited eight centuries to open their eyes and blast twaa! twaa! with their cleft tongues. At dawn they had seen that overnight the distant cupolas, the entire faade, of Sacr-Coeur appeared to be painted black. And that closer at hand, far below, the doll-sized Louvre had become transparent.

After a superficial investigation, the authorities, far off the scent, reached the conclusion that the painted faade was actually marble and the transparent Louvre had been turned to crystal. Inside the Basilica the paintings, too, were transformed; as the building had changed color, its paintings had changed race. And who was going to cross himself before the lustrous ebony of a Congolese Virgin, and who would expect pardon from the thick lips of a Negroid Christ? On the other hand, the paintings and sculptures in the Museum had taken on an opacity that many decided to attribute to the contrast with the crystalline walls and floors and ceiling. No one seemed in the least uncomfortable because the Victory of Samothrace hovered in mid-air without any visible means of support: those wings were finally justifying themselves. But they were apprehensive when they observed, particularly considering the recently acquired density in contrast to the general lightness, that the mask of Pharaoh was superimposed in a newly liberated perspective upon the features of the Gioconda, and that ladys upon Davids Napoleon. Furthermore: when the traditional frames dissolved into transparency, the resulting freeing of purely conventional space allowed them to appreciate that the Mona Lisa, still sitting with arms crossed, was not alone. And she was smiling.

Thirty-three and one half days had passed during which, apparently, the Arc de Triomphe turned into sand and the Eiffel Tower was converted into a zoo. We are confining ourselves to appearances, for once the first flurry of excitement had passed, no one even troubled to touch the sand, which still looked like stone. Sand or stone, it stood in its usual location, and after all, thats all anyone asked: Not a new arrangement, but recognizable form and the reassurance of location. What confusion there would have been, for example, had the Arc, still of stone, appeared on the site traditionally occupied by a pharmacy at the corner of the rue de Bellechasse and the rue de Babylone.

As for the tower of M. Eiffel, its transformation was criticized only by potential suicides, whose remarks revealed their unhealthy intentions and who in the end chose to play it cool in the hope that other, similar jumping places would be constructed. But it isnt just the height; perhaps even more important is the prestige of the place from which one jumps to his death, a habitu of the Caf Le Bouquet, a man who when he was fourteen had decided to kill himself at the age of forty, told Pollo Phoibee. He said this one afternoon as our young and handsome friend was pursuing his normal occupations, convinced that any other course would be like yelling Fire! in a movie theater packed with a Sunday-evening crowd.