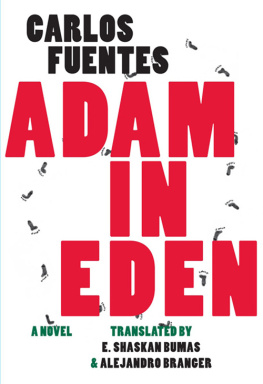

Carlos Fuentes - Christopher Unborn

Here you can read online Carlos Fuentes - Christopher Unborn full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Prose. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Christopher Unborn

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Christopher Unborn: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Christopher Unborn" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Christopher Unborn — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Christopher Unborn" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Carlos Fuentes

Christopher Unborn

The author is grateful for the help both creative and critical of his friends

JUAN GOYTISOLO and PROFESSOR ROALD HOFFMANNaturally, to my mother and my children

Prologue: I Am Created

The body is the part of our representation that is continuously being born.

Henri BergsonMexico is a country of sad men and happy children, said my father, Angel (twenty-four years old), at the instant of my creation.

Before that, my mother, Angeles (under thirty), had sighed: Ocean, origin of the gods.

But soon there shall be no time for happiness, and we shall all be sad, old and young alike, my father went on, taking off his glasses tinted violet, gold-framed, utterly John Lennonish.

Why do you want a child, then? my mother said, sighing again.

Because soon there will be no time for happiness.

Was there ever such a time?

What did you say? Things turn out badly in Mexico.

Dont be redundant. Mexico was made so things could turn out badly.

So she insisted: Why do you want a child, then?

Because I am happy, my father bellowed. I am happy! he shouted even louder, turning to face the Pacific Ocean. I am possessed of the most intimate, reactionary happiness!

Ocean, origin of the gods! And she took her copy of Platos Dialogues, the edition published in the twenties by Don Jos Vasconcelos, when he was rector of the University of Mexico, and put it over her face. The green covers bearing the black seal of the university and its motto, THROUGH MY RACE SHALL SPEAK THE SPIRIT, were stained with Coppertonic sweat.

But my father said he wanted to sire a son (me, zero years), right here while they were vacationing in Acapulco, in front of the ocean, origin of the gods? quoth Homerica Vespussy. So my naked father crawled across the beach, feeling the hot sand drifting between his legs but saying that sex is not between the legs but inside the coconut grove, around the svelte, naked, innocent body of my mother, crawling toward my mother with the volume of Plato draped over her face, Mom and Dad naked under the blazing and drunken sun of Acapulque on the day they invented me. Gracias, gracias, Mom and Dad.

What shall we name the boy?

My mother does not answer; she merely removes the tome from her face and looks at my father ironically, reprovingly, even disdainfully not to say compassionately although she doesnt dare call him a disgusting male chauvinist pig. What if its a girl? Nevertheless, she prefers to overlook the matter; he knows that somethings wrong and cant allow things to stay like that at this point in time and circumstance and so he solves the problem by nibbling at her nipples as if they were cherry-flavored gumdrops, cumdrops postprandial but prepriapic jelly beans, puns my dad, in whose prostatic sack I still lie in waiting, innocent and philadelphic, with my sleepy chromosomatic and spermatic little brothers (and sisters).

What shall we name the boy?

Things exist without anyones having to name them, she says, trying not to reactivate their old argument about the sex of the angels.

Of course, but right now Id like a taste of that pear in heavy syrup of yours.

You and I dont need names to exist, right?

All I need right now is that sweet thing of yours.

Just what I mean. Sometimes you call it the Hydra and other things.

An figs, sometimes.

And figs, sometimesmy mother laughsas your Uncle Homero would say.

Our Uncle Homero, my father jokingly corrects her. Ay! Even he didnt know if he was complaining about that undesired family tie or roaring because of the precipitate pleasure he did not want to see lost in the sterile sand, even if he knows, stretched out on his belly, that both good and evil are merely violent pleasures, and thus they resemble and cancel each other out in their infrequent eruption. As for the rest: kill time and kick ass.

Yeah, yeah, go ahead and howl, or laugh at the old guy, said Angeles, my mother, but here we are on vacation in Kafkapulco, in front of the ocean origin of the gods, guests in his home.

His home, bull, blurts out my father, Angel. It belongs by rights to the peasants from the communal lands he stripped it away from, damn the old moneybags and damn his granny, too.

Who happens also to be your granny, my mother says, because you and I say sea to refer to the sea, but who knows what its real name is, the name the gods utter when they want to stir it up and say to themselves Thalassa. Thalassa. We come from the sea.

Blessd mother of mine: thank you for your multitrack mind on one track you explain Plato; on another you fondle my father, while on a third you wonder why the baby must necessarily be a boy, why not a girl? And you say Thalassa, thalassa, well named was Astyanax, the son of Hector, well named (Angeles my mother, Angeles my wife looks toward the wrathful sea); well named was Agamemnon, whose name means admirable in his resistance (and what about my resistance, moans Angel my father, if you could only see how my Faulknerian chili pepper resists, it not only survives, it endures, it perdures, its durable stuff). Well named are all the heroes, my mother murmurs, reading at her vasconcelosite tome with its elegant Art Deco typography, to postpone with her first mental track the unrepeatable pleasure playing on the second: heroes who share the root of their identity with Eros: Eros, heroes. What shall we name the baby? What are we going to do today, January 6, 1992, Epiphany, and the anniversary of the very day of the First Agrarian Law of the Revolution, so that hes conceived on ancient lands belonging to the community improperly appropriated by our uncle and lawyer Don Homero Fagoaga, and so that he will win the Discovery of America Contest on October 12 next? In which of my mamas multitrack minds circuits and systems am I going to be onomastically inserted? I shudder to think. The paternal genes send horrible messages: Sstenes Rocha, Genovevo de la O., Caraciollo Parra Prez, Guadalupe Victoria, Pnfilo Natera, Natalicio Gonzlez, Marmaduke Grove, Assis de Chateaubriand, Archibald Leach, Montgomery Ward Swopes, Mark Funderbuck, and my mother repeats the question:

Then why do you want a son?

Because I am happy, bawls my dad. She throws away the green volume published in 1921 by the rector of the University of Mexico, Don Jos Vasconcelos, with its thick Platonic pages that survived, look now your mercies, the murders at La Bombilla and Huitzilac, the massacre of the students in Tlateloco Plaza in 1968, the principal cadavers and the subordinate cadavers, the dead with mausoleums and the dead in potters fields, those dead on marble legs and those dead without a leg to stand on: what shall we name the child? Why the fuck does it have to be a boy? Because the contest rules state:

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN: The male child born precisely at the stroke of midnight on October 12, and whose family name, not including his first name (it goes without saying the boy will be named Christopher), most resembles that of the Illustrious Navigator, shall be proclaimed PRODIGAL SON OF THE NATION. His education shall be provided by the Republic and on his eighteenth birthday he will receive the KEYS TO THE REPUBLIC, prelude to his assuming the position, at age twenty-one, of REGENT OF THE NATION, with practically unlimited powers of election, succession, and selection. Therefore, CITIZENS, if your family name happens to be Colonia, Colombia, Columbario, Colombo, Colombiano, or Columbus, not to say Coln, Colomba, or Palomo, Palomares, Palomar, or Santospirito, even why not? Genovese (who knows? perhaps none of the aforementioned will win, and in that case THE PRIZE IS YOURS), pay close attention: MEXICAN MACHOS, IMPREGNATE YOUR WIVES RIGHT AWAY!

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Christopher Unborn»

Look at similar books to Christopher Unborn. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Christopher Unborn and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.