Chinelo Okparanta

Under the Udala Trees

For Constance, Chibueze, Chinenye, Chidinma

And for Obiora

Faith is the assured expectation of things hoped for,

the evident demonstration of realities, though not beheld.

HEBREWS 11:1

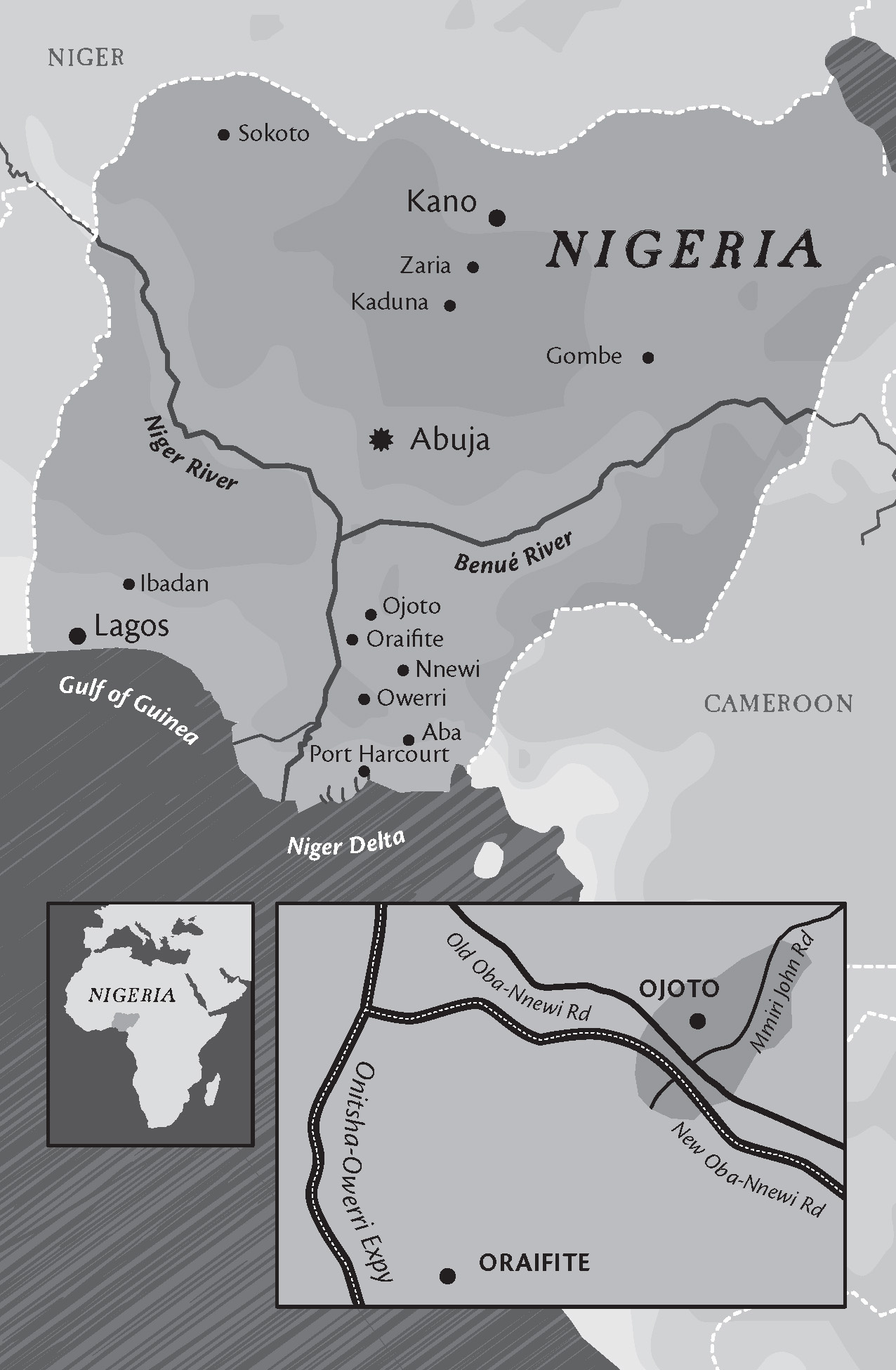

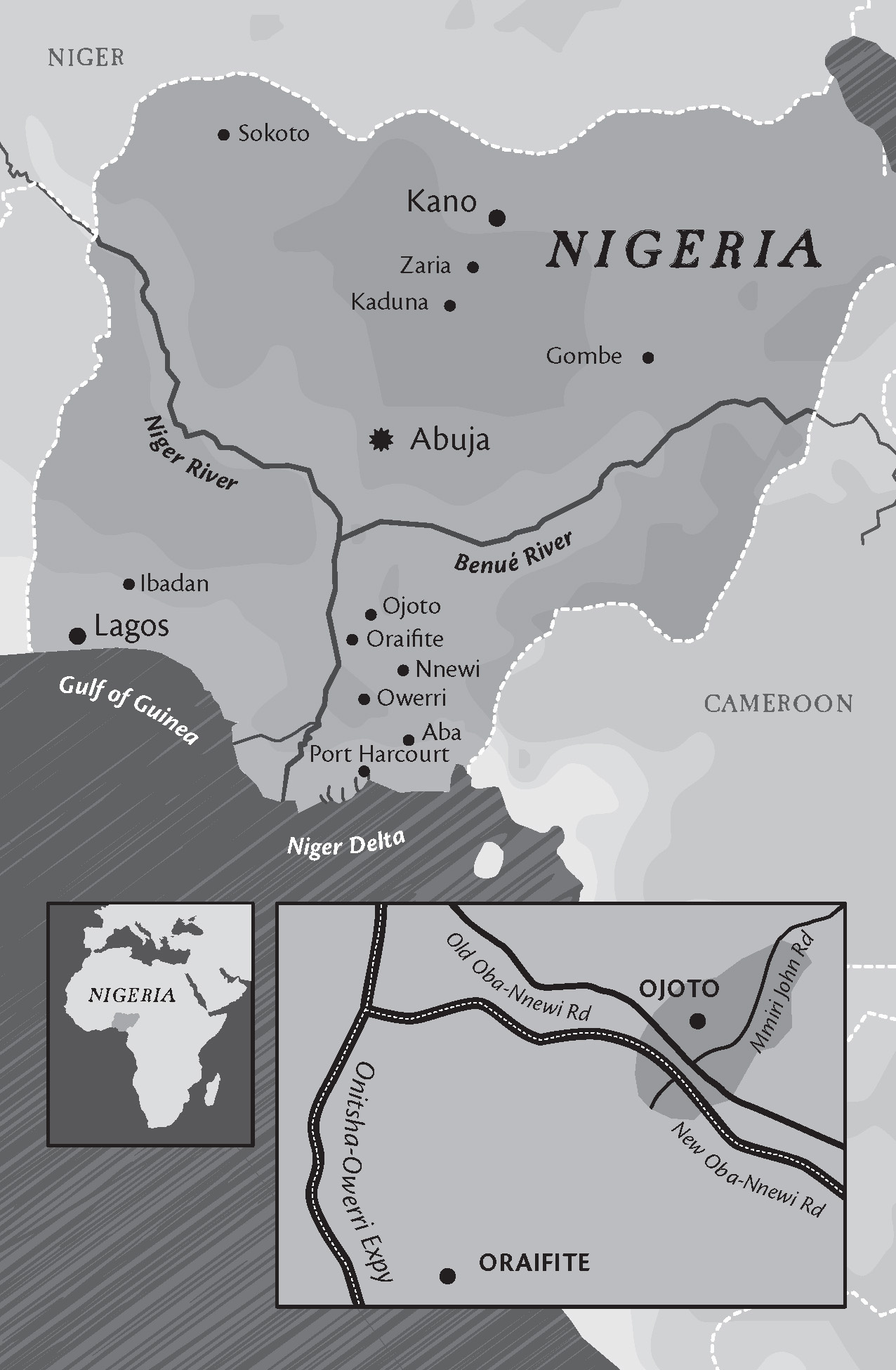

MIDWAY BETWEEN Old Oba-Nnewi Road and New Oba-Nnewi Road, in that general area bound by the village church and the primary school, and where Mmiri John Road drops off only to begin again, stood our house in Ojoto. It was a yellow-painted two-story cement construction built along the dusty brown trails just south of River John, where Papas mother almost drowned when she was a girl, back when people still washed their clothes on the rocky edges of the river.

Ours was a gated compound, guarded at the front by thickets of rose and hibiscus bushes. Leading up to the bushes, a pair of parallel green hedges grew, dotted heavily in pink by tiny, star-like ixora flowers. Vendors lined the road adjacent to the hedges, as did trees thick with fruit: orange, guava, cashew, and mango trees. In the recesses of the roadsides, where the bushes rose high like a forest, even more trees stood: tall irokos, whistling pines, and a scattering of oil and coconut palms. We had to turn our eyes up toward the sky to see the tops of these trees. So high were the bushes and so tall were the trees.

In the harmattan, the Sahara winds arrived and stirred up the dust, and clouded the air, and rendered the trees and bushes wobbly like a mirage, and made the sun a blurry ball in the sky.

In the rainy season, the rains wheedled the wildness out of the dust, and everything took back its clarity and its shape.

This was the normal cycle of things: the rainy season followed by the dry season, and the harmattan folding itself within the dry. All the while, goats bleated. Dogs barked. Hens and roosters scuttled up and down the roads, staying close to the compounds to which they belonged. Striped swordtails and monarchs, grass yellows and redtops all the butterflies flitted leisurely from one flower to the next.

As for us, we moved about in that unhurried way of the butterflies, as if the breeze was sweet, as if the sun on our skin was a caress. As if slow paces allowed for the savoring of both. This was the way things were before the war: our lives, tamely moving forward.

It was 1967 when the war barged in and installed itself all over the place. By 1968, the whole of Ojoto had begun pulsing with the ruckus of armored cars and shelling machines, bomber planes and their loud engines sending shock waves through our ears.

By 1968, our men had begun slinging guns across their shoulders and carrying axes and machetes, blades glistening in the sun; and out on the streets, every hour or two in the afternoons and evenings, their chanting could be heard, loud voices pouring out like libations from their mouths: Biafra, win the war!

That second year of the war1968Mama sent me off.

By this time, talk of all the festivities that would take place when Biafra defeated Nigeria had already begun to dwindle, supplanted, rather, by a collective fretting over what would become of us when Nigeria prevailed: Would we be stripped of our homes, and of our lands? Would we be forced into menial servitude? Would we be reduced to living on rationed food? How long into the future would we have to bear the burden of our loss? Would we recover?

All these questions, because by 1968, Nigeria was already winning, and everything had already changed.

But there were to be more changes.

There is no way to tell the story of what happened with Amina without first telling the story of Mamas sending me off. Likewise, there is no way to tell the story of Mamas sending me off without also telling of Papas refusal to go to the bunker. Without his refusal, the sending away might never have occurred, and if the sending away had not occurred, then I might never have met Amina.

If I had not met Amina, who knows, there might be no story at all to tell.

So, the story begins even before the story, on June 23, 1968. Ubosi chi ji ehihe jie: the day night fell in the afternoon, as the saying goes. Or as Mama sometimes puts it, the day that night overtook day: the day that Papa took his leave from us.

It was a Sunday, but we had not gone to church that morning on account of the coming raid. The night before, the radios had announced that enemy planes would once more be on the offensive, for the next couple of days at least. It was best for anyone with any sort of common sense to stay home, Papa said. Mama agreed.

Not far from me in the parlor, Papa sat at his desk, hunched over, his elbows on his thighs, his head resting on his fisted hands. The scent of Mamas fried akara, all the way from the kitchen, was bursting into the parlor air.

Papa sat with his forehead furrowed and his nose pinched, as if the sweet and spicy scent of the akara had somehow become a foul odor in the air. Next to him, his radio-gramophone. In front of him, a pile of newspapers.

Early that morning, he had listened to the radio with its volume turned up high, as if he were hard of hearing. He had listened intently as all the voices spilled out from Radio Biafra. Even when Mama had come and asked him to turn it down, that the thing was disturbing her peace, that not everybody wanted to be reminded at every moment of the day that the country was falling apart, still he had listened to it as loudly as it would sound.

But now the radio sat with its volume so low that all that could be heard from it was a thin static sound, a little like the scratching of skin.

Until the war came, Papa looked only lovingly at the radio-gramophone. He cherished it the way things that matter to us are cherished: Bibles and old photos, water and air. It was, after all, the same radio-gramophone passed down to him from his father, who had died the year I was born. All the grandparents had then followed Papas fathers lead the next year, Papas mother passed; and the year after, and the one after that, Mama lost both her parents. Papa and Mama were only children, no siblings, which they liked to say was one of the reasons they cherished each other: that they were, aside from me, the only family they had left.

But gone were the days of his looking lovingly at the radio-gramophone. That particular afternoon, he sat glaring at the bulky box of a thing.

He turned to the stack of newspapers that sat above his drawing paper: about a months worth of the Daily Times, their pages wrinkled at the corners and the sides. He picked one up and began flipping through the pages, still with that worried look on his face.

I went up to him at his desk, stood so close that I could not help but take in the smell of his Morgans hair pomade, the one in the yellow and red tin-capped container, which always reminded me of medicine. If only the war were some sort of illness, if only all that was needed was a little medicine.

He replaced the newspaper he was reading on the pile. On that topmost front page were the words SAVE US. Underneath the words, a photograph of a child with an inflated belly held up by limbs as thin as rails: a kwashiorkor child, a girl who looked as if she could have been my age. She was just another Igbo girl, but she could easily have been me.

Papa was wearing one of his old, loose-fitting sets of buba and sokoto, the color a dull green, faded from a lifetime of washes. He looked up and smiled slightly at me, a smile that was a little like a lie, lacking any emotion, but he smiled it still.