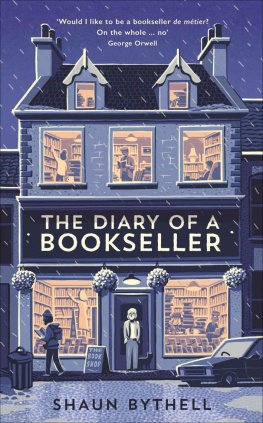

The Diary of A Bookseller

Shaun Bythell

Would I like to be a bookseller de mtier? On the whole in spite of my employers kindness to me, and some happy days I spent in the shop no.

George Orwell, Bookshop Memories, London, November 1936

Orwells reluctance to commit to bookselling is understandable. There is a stereotype of the impatient, intolerant, antisocial proprietor played so perfectly by Dylan Moran in Black Books and it seems (on the whole) to be true. There are exceptions of course, and many booksellers do not conform to this type. Sadly, I do. It was not always thus, though, and before buying the shop I recall being quite amenable and friendly. The constant barrage of dull questions, the parlous finances of the business, the incessant arguments with staff and the unending, exhausting, haggling customers have reduced me to this. Would I change any of it? No.

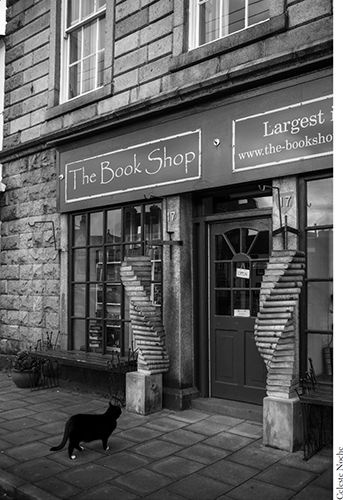

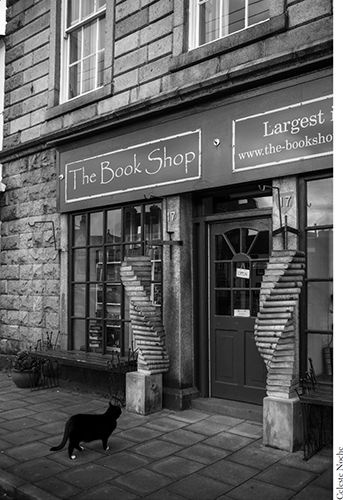

When I first saw The Book Shop in Wigtown I was eighteen years old, back in my home town and about to leave for university. I clearly remember walking past it with a friend and commenting that I was quite certain that it would be closed within the year. Twelve years later, while visiting my parents at Christmas time, I called in to see if they had a copy of Three Fevers in stock, by Leo Walmsley, and while I was talking to the owner, admitted to him that I was struggling to find a job I enjoyed. He suggested that I buy his shop since he was keen to retire. When I told him that I didnt have any money, he replied, You dont need money what do you think banks are for? Less than a year later, on 1 November 2001, a month (to the day) after my thirty-first birthday, the place became mine. Before I took over, I ought perhaps to have read a piece of George Orwells writing published in 1936. Bookshop Memories rings as true today as it did then, and sounds a salutary warning to anyone as naive as I was that the world of selling second-hand books is not quite an idyll of sitting in an armchair by a roaring fire with your slipper-clad feet up, smoking a pipe and reading Gibbons Decline and Fall while a stream of charming customers engages you in intelligent conversation, before parting with fistfuls of cash. In fact, the truth could scarcely be more different. Of all his observations in that essay, Orwells comment that many of the people who came to us were of the kind who would be a nuisance anywhere but have special opportunities in a bookshop is perhaps the most apposite.

Orwell worked part-time in Booklovers Corner in Hampstead while he was working on Keep the Aspidistra Flying, between 1934 and 1936. His friend Jon Kimche described him as appearing to resent selling anything to anyone a sentiment with which many booksellers will doubtless be familiar. By way of illustration of the similarities and often the differences between bookshop life today and in Orwells time, each month here begins with an extract from Bookshop Memories.

The Wigtown of my childhood was a busy place. My two younger sisters and I grew up on a small farm about a mile from the town, and it seemed to us like a thriving metropolis when compared with the farms flat, sheep-spotted, salt-marsh fields. It is home to just under a thousand people and is in Galloway, the forgotten south-west corner of Scotland. Wigtown is set into a landscape of rolling drumlins on a peninsula known as the Machars (from the Gaelic word machair, meaning fertile, low-lying grassland) and is contained by forty miles of coastline which incorporates everything from sandy beaches to high cliffs and caves. To the north lie the Galloway Hills, a beautiful, near-empty wilderness through which winds the Southern Upland Way. The town is dominated by the County Buildings, an imposing htel-de-ville-style town hall which was once the municipal headquarters of what is known locally as the Shire. The economy of Wigtown was for many years sustained by a Co-operative Society creamery and Scotlands most southerly whisky distillery, Bladnoch, which between them accounted for a large number of the working population. Back then, agriculture provided far more opportunities for the farm worker than it does today, so there was employment in and about the town. The creamery closed in 1989 with the loss of 143 jobs; the distillery founded in 1817 closed in 1993. The impact on the town was transformative. Where there had been an ironmonger, a greengrocer, a gift shop, a shoe shop, a sweet shop and a hotel, instead there were now closed doors and boarded-up windows.

Now, though, a degree of prosperity has returned, and with it a sense of optimism. The vacant buildings of the creamery have slowly been taken over by small businesses: a blacksmith, a recording studio and a stovemaker now occupy much of it. The distillery re-opened for production on a small scale in 2000 under the enthusiastic custody of Raymond Armstrong, a businessman from Northern Ireland. Wigtown too has seen a favourable change in its fortunes, and is now home to a community of bookshops and booksellers. The once boarded-up windows and doors are open again, and behind them small businesses thrive.

Everyone who has worked in the shop has commented that customer interactions throw up more than enough material to write a book Jen Campbells Weird Things Customers Say in Bookshops is evidence enough of this so, afflicted with a dreadful memory, I began to write things down as they happened in the shop as an aide-mmoire to help me possibly write something in the future. If the start date seems arbitrary, thats because it is. It just happened to occur to me to begin doing this on 5 February, and the aide-mmoire became a diary.

Online orders: 5

Books found: 5

Telephone call at 9.25 a.m. from a man in the south of England who is considering buying a bookshop in Scotland. He was curious to know how to value the stock of a bookshop with 20,000 books. Avoiding the obvious answer of ARE YOU INSANE?, I asked him what the current owner had suggested. She had told him that the average price of a book in her shop was 6 and that she suggested dividing that total of 120,000 by three. I told him that he should divide it by ten at the very least, and probably by thirty. Shifting bulk quantities these days is near impossible as so few people are prepared to take on large numbers of books, and the few that do pay an absolute pittance. Bookshops are now scarce, and stock is plentiful. It is a buyers market. Even when things were good back in 2001 the year I bought the shop the previous owner valued the stock of 100,000 books at 30,000.

Perhaps I ought to have advised the man on the telephone to read (along with Orwells Bookshop Memories) William Y. Darlings extraordinary The Bankrupt Bookseller Speaks Again before he committed to buying the shop. Both are works that aspirant booksellers would be well advised to read. Darling was not in fact The Bankrupt Bookseller but an Edinburgh draper who perpetrated the utterly convincing hoax that such a person did indeed exist. The detail is uncannily precise. Darlings fictitious bookseller untidy, unhealthy, to the casual, an uninteresting human figure but still, when roused, one who can mouth things about books as eloquently as any is as accurate a portrait of a second-hand bookseller as any.

Nicky was working in the shop today. The business can no longer afford to support any full-time staff, particularly in the long, cold winters, and I am reliant on Nicky who is as capable as she is eccentric to cover the shop two days a week so that I can go out buying or do other work. She is in her late forties, and has two grown-up sons. She lives in a croft overlooking Luce Bay, about fifteen miles from Wigtown, and is one of Jehovahs Witnesses, and that along with her hobby of making strangely useless craft objects defines her. She makes many of her own clothes and is as frugal as a miser, although extremely generous with what little she has. Every Friday she brings me a treat that she has found in the skip behind Morrisons supermarket in Stranraer the previous night, after her meeting at Kingdom Hall. She calls this Foodie Friday. Her sons describe her as a slovenly gypsy, but she is as much part of the fabric of the shop as the books, and the place would lose a large part of its charm without her. Although it wasnt a Friday today, she brought in some revolting food which she had pillaged from the Morrisons skip: a packet of samosas that had become so soggy that they were barely identifiable as such. Rushing in from the driving rain, she thrust it in my face and said Eh, look at that samosas. Lovely, then proceeded to eat one of them, dropping sludgy bits of it over the floor and the counter.