It was only possible to see

It was only possible to see the full extent of the town if you spent many years there. Only then could you see the barriers shimmer at its edges, and know what the edges meant.

It was only possible after many years in the town to notice the strangeness of certain aspects of familiar visions. Only then could you stand at the foot of a quiet street and at a certain time of day, and from a very specific angle, pretend that you were somewhere else. It was possible to stand at the foot of the old gasworks, and to stare upwards, and to believe that briefly you had gained access to one of those speculative worlds outside of the town.

When inside certain towns, the rest of the world disappears. So it only makes sense that to the rest of the world, certain towns are forever disappearing or else they appear as a figment, or as a ghost town, or as a spot on a map purely decorative. A spot carefully placed by a cartographer anxious to fill a lonely space.

*

When I arrived in the town

When I arrived in the town I needed to find a caf in which to regularly sit, and which would serve as headquarters for friends once I had made them. Searching a shopping plaza, I chose a Michels Patisserie in view of the Big W. At the head of the escalators a man sold Australian flag fridge magnets and tea towels. I sat inside the caf and thought: well, this is a start. I now have a location to meet people once I have met them and it is civilised.

The plaza was typical of plazas in towns of the Central West, and belonged to one of two major corporations competing for dominance in the area. I drank my first coffee and thought about my journey there, as a means to reward my past self with acknowledgement of how, back then, only hours ago, I had suspected in the back of my mind that I would not arrive anywhere at all.

Later on I wandered the plaza. I looked at the Sanity and thought about the CDs I would buy once I had found a job. Then I browsed the Angus & Robertson and made mental notes of the books I would purchase, and read, and discuss with the people I would meet in the caf opposite the Big W, once I had met them. Then I bought a cheese-and-bacon pull-apart from the Bakers Delight and sat in the food court eating.

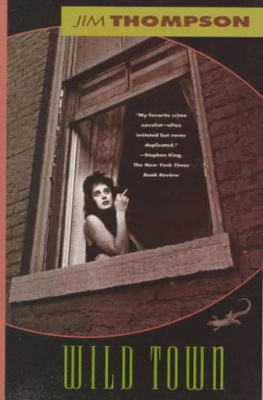

The main street of the town ran five blocks, each block bordered by minor thoroughfares that were also lined with shops. I had dreamed about this town before. In my dream there was a second storey flat on one cross-street. The flat overlooked a petrol station, and I sat on the balcony with a woman. We smoked cigarettes there, and sipped from schooner glasses of beer. I suppose this dream was born of the journeys I had made through this town in the past, along the main street, travelling from one town to some other, never stopping on the way, not even for refreshments.

This dream was not a catalyst for my arrival in the town, but when I arrived on that day I tricked myself into believing it was. It was an important dream, I recall thinking, hoping to lend gravity to the occasion, though I knew at the time that I was lying to myself. It was a harmless thing to lie to oneself about.

*

I moved in with a person named Rob

I moved in with a person named Rob. He sublet me a room in a townhouse near the school, advertised in the local daily paper. Though I was eager to meet people I was not eager to know more about Rob, as he was very enthusiastic about sport. He asked what team I barracked for and I said Australia. Occasionally Rob and his friends would watch sport in the lounge room while drinking. They exchanged earnest appraisals of each sportsman, and spoke of these sportsmen in a manner that suggested they had mingled with them in real life.

I paid rent directly to Rob, who delivered it to his landlord parents. Every week I left a sealed envelope in the kitchen drawer marked rent. At times when it was impossible to avoid coming into direct contact with Rob we would talk about our plans for the weekend, even if it was Tuesday. Once I told Rob that I was writing a book about the disappearing towns in the Central West region of New South Wales. He told me that he was going to have a beer.

Rob showed no interest in me until one night after some grand final, when arriving home late he found me cooking my dinner in the kitchen. He told me he was surprised how rarely I left the house, and that a grand final offers the perfect occasion to get among it. I lied that this day was the anniversary of my fathers death, and that besides, I was working on my book about the disappearing towns. This time he seemed to admire that I was attempting to write a book, and asked whether he would ever be allowed to read it. I told him he was welcome to read it whenever he liked, finished or not, because this book was falling from my mind to page in what I believed at the time to be a fully formed state. I doubted I would even need to edit it, let alone write a second draft, because this book was a very easy one to write. It would be no masterpiece, but it certainly would be a book. Rob said he would like to read some of my book right that very second, so I lead him into my bedroom, sat him in front of my computer and flicked to a passage I believed to be especially interesting.

The passage was about the town Meranburn. I had written it in a daze. Days previously I had written it feeling as if I were sitting cross-legged in the dirt by the derelict station at Meranburn. Rob read it, and wanted to know where Meranburn was, so I told him that it was necessary to speak of Meranburn in the past tense, since it no longer existed. He suggested that it was a ghost town, to which I replied that it was not a ghost town, not as he understood what a ghost town was. Meranburn had not deteriorated economically, its residents had not flocked to the closest regional towns in search of work, the buildings had not been dismantled. Meranburn had simply disappeared. Hence the name of the book, Rob said, The Disappearing Towns of the Central West. He did not go on to say whether he enjoyed or disliked the passage, only that he was now curious about the town of Meranburn. And, he said, that actually, its not really disappearing, is it. Its disappeared.

*

I got a job stacking shelves

I got a job stacking shelves at the Woolworths. I bought a personal recorder so that I could record myself reading at home, in order to listen as I carefully placed items. As a shelf-stacker I was not much called upon to communicate with people, though customers would often ask for help finding this or that item, to which I would always reply that I did not know where it was.

Sometimes I would become disaffected with my book while listening to my dictations at the supermarket. I wanted there to be a section, or a chapter, or even just a passage, which would truly horrify people. I wanted there to be something embedded in my writing that filled a reader with dread. I wanted there to be a single passage which would reflect my vague notion that the disappearing towns of the Central West of New South Wales needed to be as important to the reader and the world as they were to me. During these fits of disaffection, a certain image would appear in my mind: a crisp green grass plain, and standing in it naked people being flayed by a cloaked figure. I supposed, during my evenings packing the shelves, that it might be interesting to have that scene conclude my book, that it could be the culmination of all my isolated chapters about each separate town. Maybe each citizen of each town had been abducted and flayed in some remote field towards Dubbo. The location of this plain was always the same: in the region just before the green slopes and plains give way to the browner flatness which prevails much farther into the rest of the country. The book would contain eight chapters of flat journalistic prose describing what may have occurred in the disappeared towns of the Central West. None of these eight speculations would be particularly violent or even interesting, but then this final ninth chapter about the naked people being flayed by the cloaked figure would close the book, and in doing so it would manage to create the effect that this scene was somehow factually related to everything in the book that preceded it. It would never be explained, but it would be true. The reader would believe that the chapter was intrinsically related to the stories about the disappearing towns of the Central West of New South Wales.