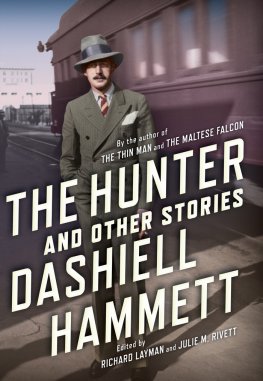

Dashiell Hammett

The Hunter and Other Stories

All previously unpublished stories, copyright 2013 The Literary Property Trust of Dashiell Hammett

Introduction and commentary on Crime and Men and Women, copyright 2013 Richard Layman

Afterword and commentary on Men, Screen Stories, and Appendix, copyright 2013 Julie M. Rivett

The Diamond Wager (Detective Fiction Weekly, 19 October 1929; uncollected) copyright 1929, Dashiell Hammett; Faith (published in The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps, ed. Otto Penzler; New York: Vintage, 2007) copyright 2007, The Literary Property Trust of Dashiell Hammett; The Cure (published as So I Shot Him in The Strand Magazine, Feb.-May 2011; uncollected) copyright 2011, The Literary Property Trust of Dashiell Hammett; Seven Pages (published in Discovering the Maltese Falcon and Sam Spade, ed. Richard Layman; San Francisco: Vince Emery Productions, 2005) copyright 2005, The Literary Property Trust of Dashiell Hammett; On the Way (Harpers Bazaar, March 1932; uncollected) copyright 1932, Dashiell Hammett

Call this volume Hammett Unplugged. It includes seventeen short stories and three screen stories, none previously collected and most previously unpublished, that stand in significant contrast to the work for which he is best known while exhibiting the best qualities of his literary genius. The earliest of the stories in this collection seem to date from near the beginning of Hammetts writing career, and the latest might well mark the end of it. In the stories included in this volume Hammett was breaking boundaries. This collection includes no stories from Black Mask magazine, the detective pulp where Hammett made his reputation as a short-story writer; it includes no stories featuring the Continental Op, Hammetts signature short-story character; and it includes only one story narrated by the main character, which was Hammetts preferred approach in most of his best-known short fiction. Here he addresses subjects, expresses sentiments, and explores ideas that would have fit uneasily in the pages of Black Mask. In these stories Hammett displays his fine-tuned sense of irony and explores the complexities of romantic encounters. He confronts basic human fears and moral dilemmas. He is sometimes sensitive and more often stonily objective. He caricatures prideful men, draws sympathetic portraits of strong women, and parodies pulp-fiction plots. And violence takes a back seat to character development.

The story of Hammetts career as a writer is well-known. He published his first story in October 1922 at the age of twenty-eight, after his career as a Pinkertons detective had been cut short by tuberculosis. He wrote to survive. Severely disabled during most of the 1920s, he was unable to provide for his wife and family in any other way. After a brief attempt to break into the slick-paper (which is to say middle-class) short-story market, he found his home as a writer in the pages of the detective pulps, aimed at blue-collar, primarily male readers. He drew on his five years as a Pinkerton operative to write stories that had the authority of experience, and soon he became the most popular writer for the most popular of the detective-fiction pulps. He came to regard that distinction as a mixed blessing; he had broader interests. Of forty-nine stories Hammett published before June 1927, half neither feature a detective nor are about crime. Of the eleven new stories that appeared after The Maltese Falcon was published in 1930, five are about noncrime subjects.

With the April 1, 1924, issue, which carried Hammetts fourteenth Black Mask story, the sixth featuring the Continental Op, a new editor took over at the magazine. Phil Cody had been circulation manager for Black Mask, and though he described himself as primarily a businessman, he took an aggressive stance as an editor. Cody insisted that the quality of the writing in his pages be elevated, championing Hammett as a model for his other writers and imposing what might be called the Black Mask editorial formula on his authors. Cody encouraged longer, more violent stories, and he insisted on action and adventure in the fiction he published rather than simply what the previous editor called unusual subject matter. The main characters of the stories Cody published were masters of their world, offering readers vicarious triumph over the threats and frustrations of modern urban life. Cody the businessman set about cultivating a dedicated readership who knew what to expect issue after issue. From Hammett, Black Mask readers expected the Continental Op.

Hammett flourished under Codys editorship. But as he began to take his editors compliments to heart, as he developed a surer confidence in his writing ability, and as his financial situation became more stressed when his wife became pregnant with their second daughter, he asked for more money and was denied. Hammett didnt take no well. By the end of 1925, he decided that he had had enough of Cody and his magazine, and he said so before quitting. In November of that year he wrote a letter to Black Mask, apparently a response to Codys solicitation of his opinion about the most recent issue. Hammett warned him, Remember, Im hard to get along with where fictions concerned. He then offered perceptive criticism of each story in the issue, concluding with the comment that three of the stories simply... didnt mean anything. People moved around doing things, but neither the people nor the things they did were interesting enough to work up a sweat over. Hammett was busy by that time writing stories for other markets in which interesting people from various walks of life do interesting things. Those stories are in this volume.

In fall 1926, Cody became circulation manager and vice president of Black Mask parent company Pro-Distributors, and Joseph T. Shaw was named the new editor of the magazine. Shaws first move was to attempt to lure Hammett back into the fold. He offered more money and promised to support Hammetts literary ambitions. Hammett, who needed the money to help support his growing family, capitulated. Over the next two years he focused on Black Mask with stories that were longer and more violent than ever before. When the editors at Knopf, Hammetts hardback publisher, read his first two novels, Red Harvest (1929) and The Dain Curse (1929), both of which had first appeared serially in Black Mask, they responded in both instances that the violence is piled on a bit thick. With that, Hammett turned to tough-minded dramatic confrontation rather than violence as a means of advancing his plots. As he famously told Blanche Knopf in 1928, he was trying to make literature of his work. These stories document his efforts to that end.

He was also trying to make more money from his work. Perhaps because his health was improving a bit, clearly because of his pressing financial needs, Hammett began promoting his writing career with renewed energy in 1928. He sent his first novel to Knopf, unagented, and they accepted it for publication. The same year, he traveled south to Hollywood to try to sell his stories for adaption as movies. By that time the new sound movies were clearly about to transform the movie industry, and Hammett wanted in on the action. He began writing fiction in a form that could be easily filmed paying attention to restrictions of time, place, and action. It is fair to say that by the end of 1929, Hammetts fiction was shaped by an intent to make not just literature, but movies of his work. By 1930, he had sold Red Harvest (the unrecognizable basis for Roadhouse Nights [1930] featuring Helen Morgan, Charles Ruggles, and Jimmy Durante in his first movie role) and The Kiss-Off, which was the original story for