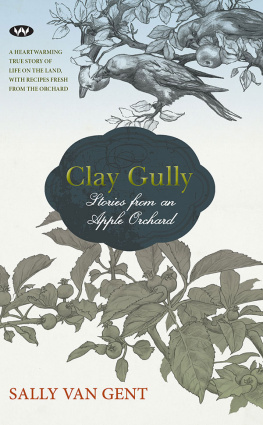

Tracy Chevalier

At the Edge of the Orchard

Copyright Tracy Chevalier 2016

For Claire and Pascale

finding their way in the world

The juice of Apples likewise, as of pippins, and pearemaines, is of very good use in Melancholicke diseases, helping to procure mirth, and to expell heavinesse.

John Parkinson,

Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1629

To the spirit bowed with affliction, or harrowed with cares, a pilgrimage to these shadowy shrines affords most soothing consolation. Behold the evergreen summits of trees that have withstood the storms of more than three thousand years! While lost in wonder and admiration, the turmoil of earthly strife seems to vanish.

Edward Vischer,

The Mammoth Tree Grove, Calaveras County, California, 1862

Go West, young man, and grow up with the country.

John Babsone Lane Soule, 1851 and Horace Greeley, 1865

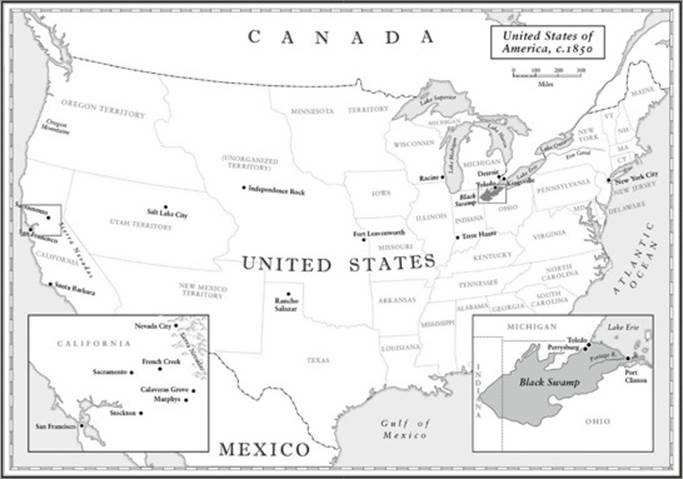

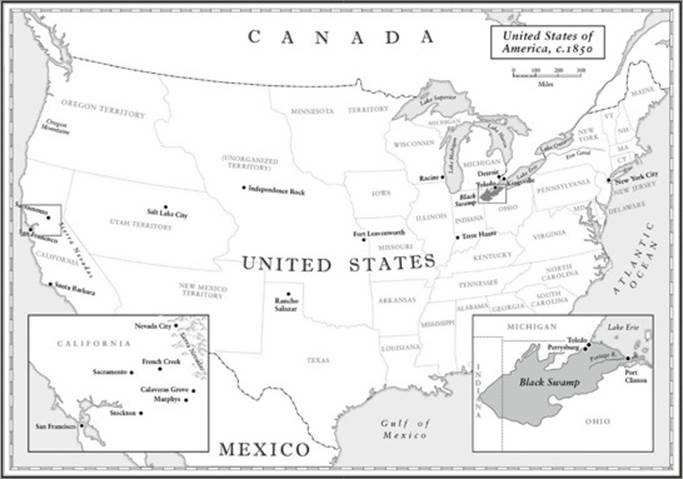

Black Swamp, Ohio: Spring 1838

THEY WERE FIGHTING OVER apples again. He wanted to grow more eaters, to eat; she wanted spitters, to drink. It was an argument rehearsed so often that by now they both played their parts perfectly, their words flowing smooth and monotonous around each other since they had heard them enough times not to have to listen anymore.

What made the fight between sweet and sour different this time was not that James Goodenough was tired; he was always tired. It wore a man down, carving out a life from the Black Swamp. It was not that Sadie Goodenough was hung over; she was often hung over. The difference was that John Chapman had been with them the night before. Of all the Goodenoughs, only Sadie stayed up and listened to him talk late into the night, occasionally throwing pinecones onto the fire to make it flare. The spark in his eyes and belly and God knows where else had leapt over to her like a flame finding its true path from one curled wood shaving to another. She was always happier, sassier and surer of herself after John Chapman visited.

Tired as he was, James could not sleep while John Chapmans voice drilled through the cabin with the persistence of a swamp mosquito. He might have managed if he had joined his children up in the attic, but he did not want to leave the bed across the room from the hearth like an open invitation. After twenty years together, he no longer lusted after Sadie as he once had, particularly since applejack had brought out her vicious side. But when John Chapman came to see the Goodenoughs, James found himself noting the heft of her breasts beneath her threadbare blue dress, and the surprise of her waist, thicker but still intact after ten children. He did not know if John Chapman noticed such things as well-for a man in his sixties, he was still lean and vigorous, despite the iron gray in his unkempt hair. James did not want to find out.

John Chapman was an apple man who paddled up and down Ohio rivers in a double canoe full of apple trees, selling them to settlers. He first appeared when the Goodenoughs were new arrivals in the Black Swamp, bringing his boatload of trees and mildly reminding them that they were expected to grow fifty fruit trees on their claim within three years if they wanted to hold on to it legally. In the laws eyes an orchard was a clear sign of a settlers intention to remain. James bought twenty trees on the spot.

He did not want to point a finger at John Chapman for their subsequent misfortunes, but occasionally he was reminded of this initial sale and grimaced. On offer were one-year-old seedlings or three-year-old saplings, which were three times the price of seedlings but would produce fruit two years sooner. If he had been sensible-and he was sensible!-James would simply have bought fifty cheaper seedlings, cleared a nursery space for them and left them to grow while he methodically cleared land for an orchard whenever he had the time. But it would also have meant going five years without the taste of apples. James Goodenough did not think he could bear that loss for so long-not in the misery of the Black Swamp, with its stagnant water, its stench of rot and mold, its thick black mud that even scrubbing couldnt get out of skin and cloth. He needed a taste to sweeten the blow of ending up here. Planting saplings meant they would have apples two years sooner. And so he bought twenty saplings he could not really afford, and took the time he did not really have to clear a patch of land for them. That put him behind on planting crops, so that their first harvest was poor, and they got into a debt he was still paying off, nine years on.

Theyre my trees, Sadie insisted now, laying claim to a row of ten spitters James was planning to graft into eaters. John Chapman gave em to me four years ago. You can ask him when he comes back-hell remember. Dont you dare touch em. She took a knife to a side of ham to cut slices for supper.

We bought those seedlings from him. He didnt give them to you. Chapman never gives away trees, only seeds-seedlings and saplings are worth too much for him to give away. Anyway, youre wrong-those trees are too big to be from seeds planted four years ago. And theyre not yours-theyre the farms. As he spoke James could see his wife blocking out his words, but he couldnt help piling sentence upon sentence to try to get her to listen.

It needled him that Sadie would try to lay claim to trees in the orchard when she couldnt even tell you their history. It was really not that difficult to recall the details of thirty-eight trees. Point at any one of them and James could tell you what year it was planted, from seed or seedling or sapling, or grafted. He could tell you where it came from-a graft from the Goodenough farm back in Connecticut, or a handful of seeds from a Toledo farmers Roxbury Russet, or another sapling bought from John Chapman when a bear fur brought in a little money. He could tell you the yield of each tree each year, which week in May each blossomed, when the apples would be ready for picking and whether they should be cooked, dried, pressed or eaten just as they were. He knew which trees had suffered from scab, which from mildew, which from red spider mite and what you did to get rid of each. It was knowledge so basic to James Goodenough that he couldnt imagine it would not be to others, and so he was constantly astonished at his familys ignorance concerning their apples. They seemed to think you scattered some seeds and picked the results, with no steps in between. Except for Robert. The youngest Goodenough child was always the exception.

Theyre my trees, Sadie repeated, her face set to sullen. You cant cut em down. Good apples from them trees. Good cider. You cut one down and well be losing a barrel of cider. You gonna take cider away from your children?

Martha, help your mother. James could not bear to watch Sadie work with the knife, slicing uneven steaks too thick at one end, too thin at the other, her fingers threatening to be included in their supper as well. She was bound to keep cutting steaks until the whole ham was chopped up, or lose interest and stop after only three.

James waited until his daughter-a leaf of a girl with thin hair and pinched gray eyes-continued with the slicing. The Goodenough daughters were used to taking over the making of meals from their mother. Im not cutting them down, he explained once more to Sadie. Im grafting them so theyll produce sweet apples. You know that. We need more Golden Pippins. We lost nine trees this winter, most of them eaters. Now we got thirty-five spitters and just three eaters. If I graft Golden Pippins onto ten of the spitters, thatll give us thirteen eaters in a few years. We wont have so many trees producing for a while, but in the long run it will suit our needs better.

Next page