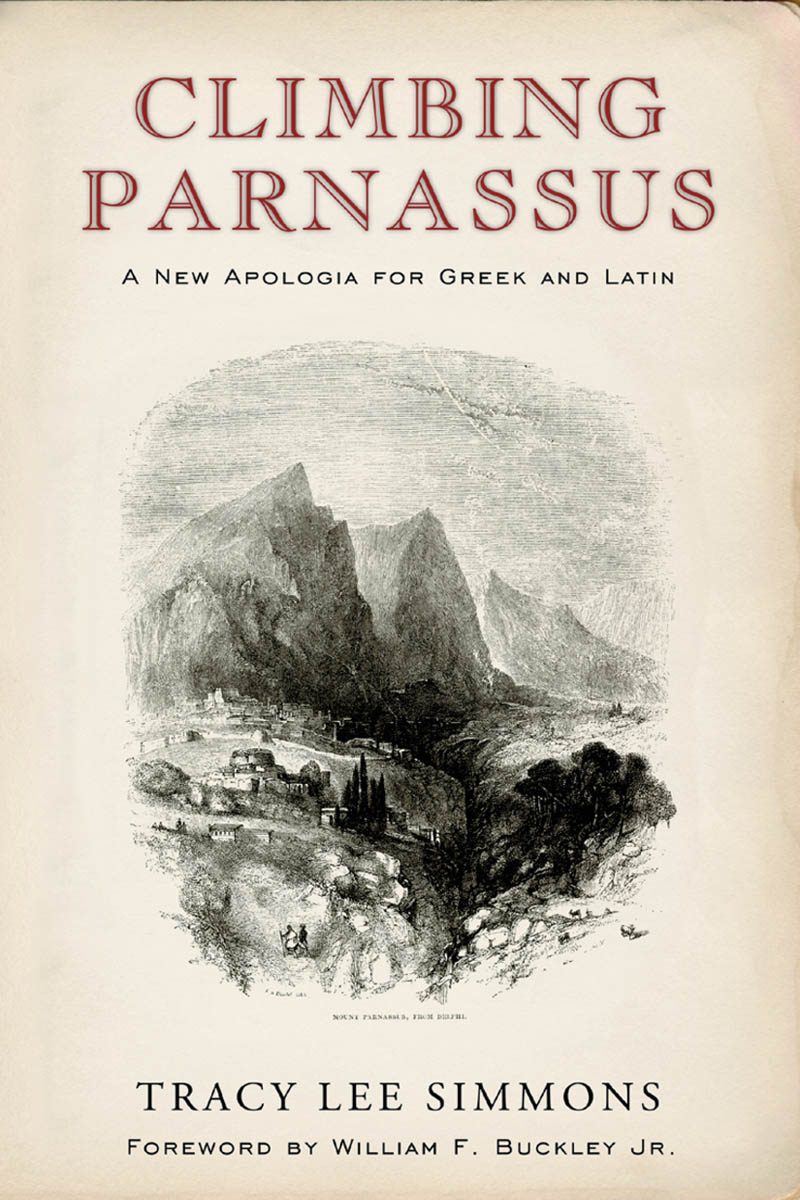

C LIMBING

P ARNASSUS

A New Apologia for Greek and Latin

T RACY L EE S IMMONS

WILMINGTON , DELAWARE

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright 2002 by ISI Books

ISBN: 978-1-4976-5139-5

Published by ISI Books

Intercollegiate Studies Institute

3901 Centerville Road

Wilmington, DE 19807-1938

www.isibooks.org

Distributed by Open Road Distribution

345 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

www.openroadmedia.com

To Scot Hicks

Il miglior umanista

PARNASSUS (mod. Likoura or Likeri), a mountain of Greece, 8070 ft., in the south of Phocis, rising over the town of Delphi. It had several prominent peaks, the chief known as Tithorea and Lycoreia (whence the modern name). Parnassus was one of the most holy mountains in Greece, hallowed by the worship of Apollo, of the Muses, and of the Corycian nymphs, and by the orgies of the Bacchantes. Two projecting cliffs, named the Phaedriadae, frame the gorge in which the Castalian spring flows out, and just to the west of this, on a shelf above the ravine of the Pleistus, is the site of the Pythian shrine of Apollo and the Delphic oracle. The Corycian cave is on the plateau between Delphi and the summit.

Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th edition

Acknowledgments

While very little research of the original kind went into this essay, it is nonetheless the fruit of many years reading, thinking and, most of all, hundreds of beer-, sherry-, or whisky-soaked conversations with teachers, mentors, friends, and colleagues, not all of whom work professionally in the harvest fields of classics. I must render special thanks to my friend and former supervising don Michael Winterbottom, lately Corpus Christi Professor of Latin at Oxford, as well as Stephen Harrison, Donald Russell, the late Don Fowler, and Jasper Griffin, also of Oxford. Harold C. Gotoff and A. J. Christopherson have also inspired this small work in ways they cant even know. My brazen exaggerations and missteps have arisen in spite of, not because of, their teaching, advising, and erstwhile companionship. Yet just as much I must thank the friends and comrades who acted as first sounding boards for this fanciful opusculum: Scot Hicks, Wolfgang Grassl, Andrew Oliver II, Richard Brookhiser, Joseph Epstein, Robert Royal, James Taylor, Jack Taylor, Richard Seymann and, ever and always, the late Sheldon Vanauken.

I must also thank Jeffrey O. Nelson and Jeremy Beer of ISI Books, who, from its inception, saw through the outlandish idea for this book courageously and with expert editorial advice and direction.

Contents

Liberal Education, the Humanities, and the Quest for a Common Mind: The Foothills of Classical Education

The Long Ascent of Classical Education from Ancient to Modern Times

The Balms of Greek and Latin

FOREWORD

I first came across the name of this books author when I read his review of one of my sailing adventures. I was attracted immediately by the lucidity of his writing style and by the generosity of his mind. Subsequently I encouraged a professional association that brought him, as an associate editor, to National Review, which I then served as editor-in-chief. A friendship evolved, and as it did I became privy to his deep, and almost secret, devotion to the classical world. He has reveled in the literatures he here celebrates, in the languages Greek and Latin he loves, and pleads now, as fervently as someone recovered from deafness and exposed to music might do, that we understand the joy he has found, and labor to unplug our own ears.

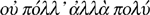

Relax. Tracy Lee Simmons is not telling us to get off the bus and hire a Latin teacher. We arent going to do this, most of us, but that doesnt matter, any more than a written description of music would gall the deaf man. He wants us to know what is there, accumulated over millennia, and ponder its historic achievements and unique tones of voice. (Not to know Greek is to be ignorant of the most flexible and subtle instrument of expression which the human mind has devised, he quotes one old author, and not to know Latin is to have missed an admirable training in precise and logical thought.) Simmons does not play the pedant in this graceful testimonial to the classical languages. He is the eager and eloquent reporter giving us some idea of what lies in those great repositories, so inexplicably neglected in modern schooling, and what pleasures await those whose curiosity he succeeds in awakening and how gratefully the mind repays itself when flexed on languages which are not dead because, as he quotes another author, they are no longer mortal.

Our author is greatly learned, but he rebuffs any suggestion that he is a scholar or an academic. Only in this exercise in self-abasement is he unconvincing whatever it is that he chooses to call himself, we (I, certainly) might wish we could qualify to call ourselves. He is of course the teacher, but also the journalist, and he sets out in this book to write about the classical heritage informatively and unpretentiously. And, I should stress, readably; which he succeeds in doing, probably without even noticing the odes he brings to our attention by sharp-eyed scholars who have acclaimed, for instance, the mastery of Latin because, in part, it engenders a verbal sensitivity and dexterity that lead to good writing and, prospectively, fine writing.

Mr. Simmons manages something else, difficult to do. At once he unequivocally rejects the proposition that all practitioners are equal, that just as we assert our equality at the voting booth, we cannot assume equality in achievement or in the capacity to enjoy. I welcome his ample reminder of Albert Jay Nocks stern lectures at the University of Virginia in 1931, in which Nock ate alive the preposterous idea that all who check in at school are educable, let alone equally educable. But Mr. Simmons is more genial, really, than Mr. Nock ever was, and his effort in pointing out the glory and the joys resulting from any attempt to climb Parnassus that ancient peak symbolizing the source of inspiration and eloquence never gives way to the exclusionist appetite of Nock. In this matter he is in the good company of Mortimer Adler, who never suggested that even his own students could rise as high as he wished, but adamantly insisted that efforts to learn were rewarding, however modest ones achievement, while Parnassus itself must always stand undiminished and hallowed. Nocks elitism can be read as a fatalistic consignment of the great body of students to the assembly-line life of the kind Charlie Chaplin memorialized. Not Simmons. No, he is here the bard of the classical legacy, and ends not by rejecting suitors, but by seducing them.

I reproduce from this book the autobiographical passage from Evelyn Waugh, because it is supremely informative, and because it achieves so masterfully the sweetness of the perfect prose Simmons envisions and encourages: