For Allison, Audrey, Carolyn, Verity, Melanie, Evie, Ellie,

James (a boy at last!) and Violet

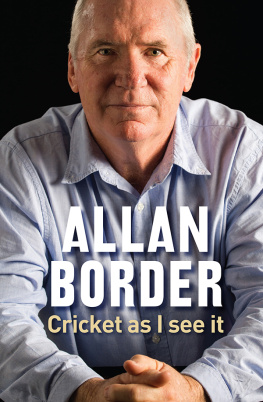

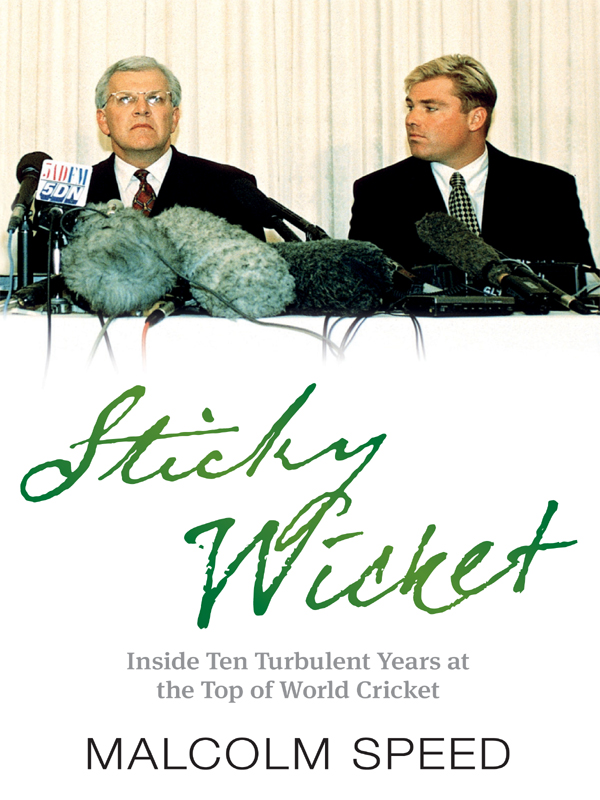

T his is a book that had to be written, and by someone who was on the inside of cricket during some of its more turbulent times. Cricket has never been a gentle game; even from the time it began hundreds of years ago, teams were owned or captained by English noblemen who played for money and were not averse to a bit of gambling on the side. One hundred and ninety-three years ago William Lambert, the leading professional cricketer in England, was banned from playing at Lords for accepting bribes to play well, or play badly. The previous year he had made a century in each innings of a match. Every club cricket ground in England had a pub just near the boundary edge where ale was available and many bets were laid and some losers even paid.

Malcolm Speed had more of a background in basketball than cricket, though he did play the game. He was successful sports administrator more than a player, but he had a good feeling for sport. There was some chaos within the circle of the Australian Cricket Board (ACB) when Speed made his first appearance as a cricket administrator. Malcolm was two years away from turning 50 when a telephone call came from a representative of the ACB, but he said he wasnt interested in an administrative position on the basis that cricket had always preferred to appoint administrators from within their own circle.

This came after Graham Halbish, the Chief Executive Officer, had been told his services were no longer required, but he soon found a good job elsewhere, working with the Players Association; something of a twist in the circumstances. It was a time of tumult in Australian cricket and Malcolm Speed has chronicled it all in this book which widely covers areas involving corruption in cricket, alleged racism, the Darrell Hair court case in the United Kingdom and the impression of efficiency he made on a young executive, James Sutherland. James was later to become the CEO of Cricket Australia. He was qualified as a Chartered Accountant and had been for six years the chief financial officer at Carlton Football Club in the AFL. He had played first-class cricket for Victoria, also one-day matches, and he was assistant cricket coach for Victoria at the time.

Mr Speeds chapters on cricket corruption in Pakistan and in Australia should be carefully noted, because it is alleged the game is in the midst of more problems in that regard. International players were to be charged in March 2011 by the UK Crown Prosecution Service; the allegation was conspiracy to accept corrupt payments. The International Cricket Councils Tribunal also issued their findings on various matters in February 2011. Readers will find in the pages that follow some very unusual if not fascinating happenings in the world of sport.

Richie Benaud

I n January 2008 I was in the final stretch I had completed a decade in cricket as a chief executive, first as head of Australian cricket (ACB) for four years and then six and a half years at the International Cricket Council (ICC), the world governing body. I was due to retire in July.

It was a decade that had covered the most tumultuous period in the history of world cricket. The great and ancient game underwent massive change in its power base, its financial and economic imperatives, its culture and its spirit.

As CEO of Australian cricket and then world cricket, I had a ringside seat. In fact, I was often in the ring throwing a few punches and, more often than not, connecting with air or failing to duck at the right time.

As I reflect on this decade in 2011, three years after my departure, and seek to assess my success or otherwise, I fall back to a cricket analogy. I was playing on a sticky wicket a pitch that is in the process of drying and on which batting is awkward and hazardous, as the ball will spin, seam and bounce sharply and unpredictably.

During this period, the game was challenged by drama corruption, chucking, technology, player behaviour, doping, terrorism, wars, politics (internal and external), Zimbabwe and the emergence of India as a cricketing superpower that was prepared to use its muscle. Cricket welcomed a new, shorter form of the game, Twenty20, and it embraced huge revenue increases from television rights and sponsorship.

As with any job, if you work in a sport long enough you see beneath its skin: you understand what makes it tick, you know when it is strong and when it is ailing, you revel in its greatness, you fight against its ugliness. You hear its heart, analyse its DNA and see changes in its character as it adapts to changes in society. On rare and privileged occasions you see deep into its soul.

At a personal level, I was burned in effigy on several occasions; described in The Hindustan Times as one of the most disliked men in India nominated as public enemy number one by the Sydney Morning Herald when I sought to justify the Australian Cricket Boards (ACBs) decision to sell the naming rights to the century-old Sheffield Shield so that it became the Pura Milk Cup; booed by a packed house at the ICC Cricket World Cup Final in Barbados in 2007; and involved on the fringes of two murder investigations. I was despatched on gardening leave two months before I completed my seven-year term as CEO of the ICC.

Over that period I made thousands of friends and a few enemies. Fascinating characters with a multitude of motives populate cricket. Part of the attraction of my roles was to deal with interesting people on difficult issues.

This book seeks to chronicle the journey of the game from my perspective, as one of its privileged custodians during those fascinating years.

C ricket is played at a serious level by a small number of nations countries where the British introduced the game in the 19th century. It seeks to bring together Muslim, Hindu, Christian, Buddhist and atheist at a time when religion divides rather than unites much of the world.

The countries of the Indian sub-continent account for approximately one-fifth of the worlds population and they are passionate beyond belief about cricket. It is the most popular sport in India by a factor of about 30. It penetrates all levels of society and is a terribly important feature of the sub-continental psyche.

The major area of change revolved around India taking over the game, and much has been written about the financial clout and leverage of Indian cricket.

It is important at the outset to understand why India is so powerful.

In 2000, David Fouvy, the ACBs General Manager of Marketing, was quite excited after meeting with ACBs media rights advisers, Octagon. They had confirmed his suspicions that the value of TV rights in India had increased significantly as the population of the worlds second most populous nation had acquired television sets and tuned in to cricket matches involving India. ACBs rights from selling television pictures of Australian cricket into India were about to quadruple, and each four years thereafter they quadrupled again. Playing cricket against India as often as possible became a key objective for all of the cricket playing nations.

Indias power flows from the commercial arrangements that are attached to tours by India to other countries. All sports have a formula for sharing revenue. Under the ICC model, the host country sells TV rights, sponsorship and tickets for its home series. When India tours Australia, Australia sells to the Indian broadcasters, and the value of the Indian rights now far exceeds the rights of any other country.