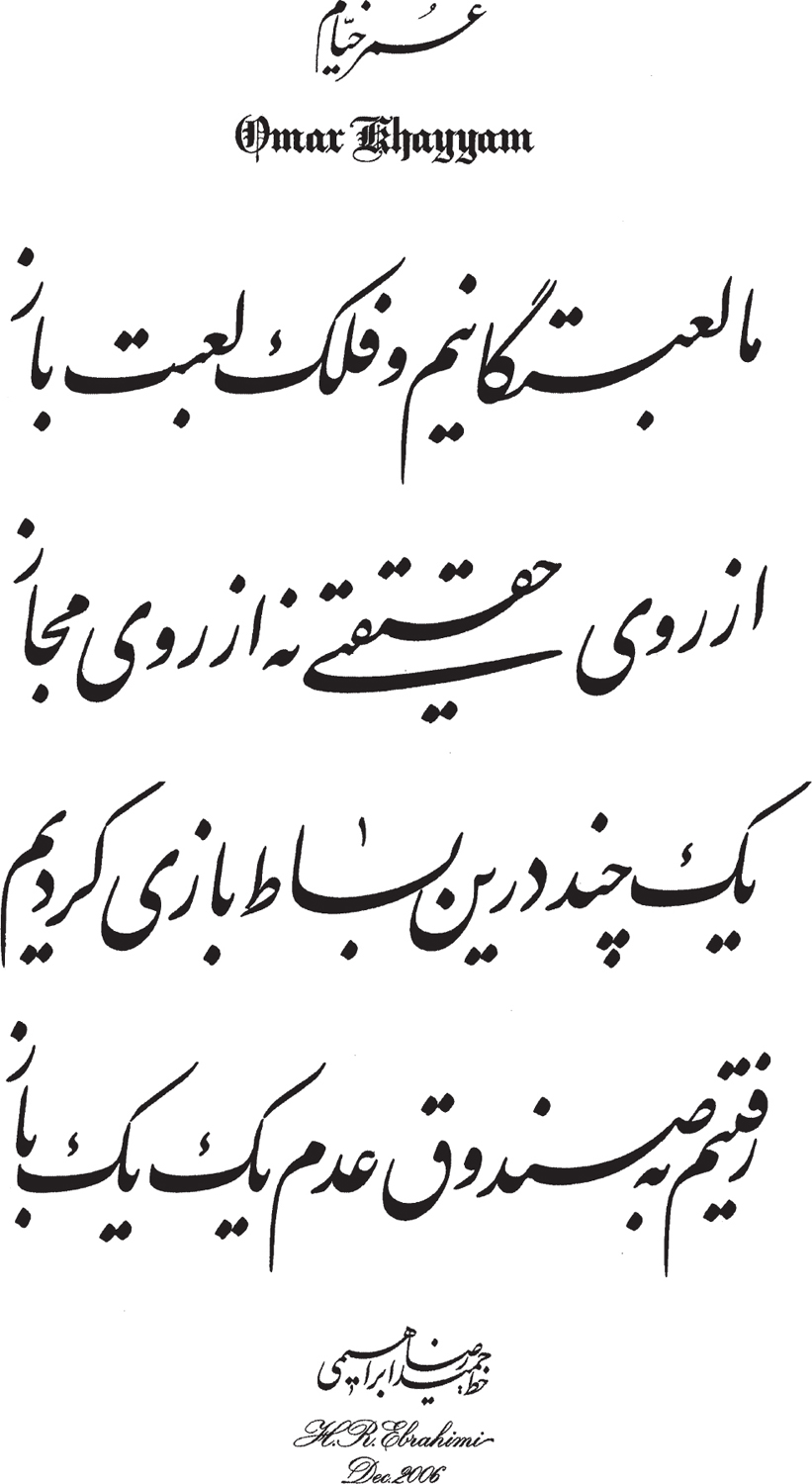

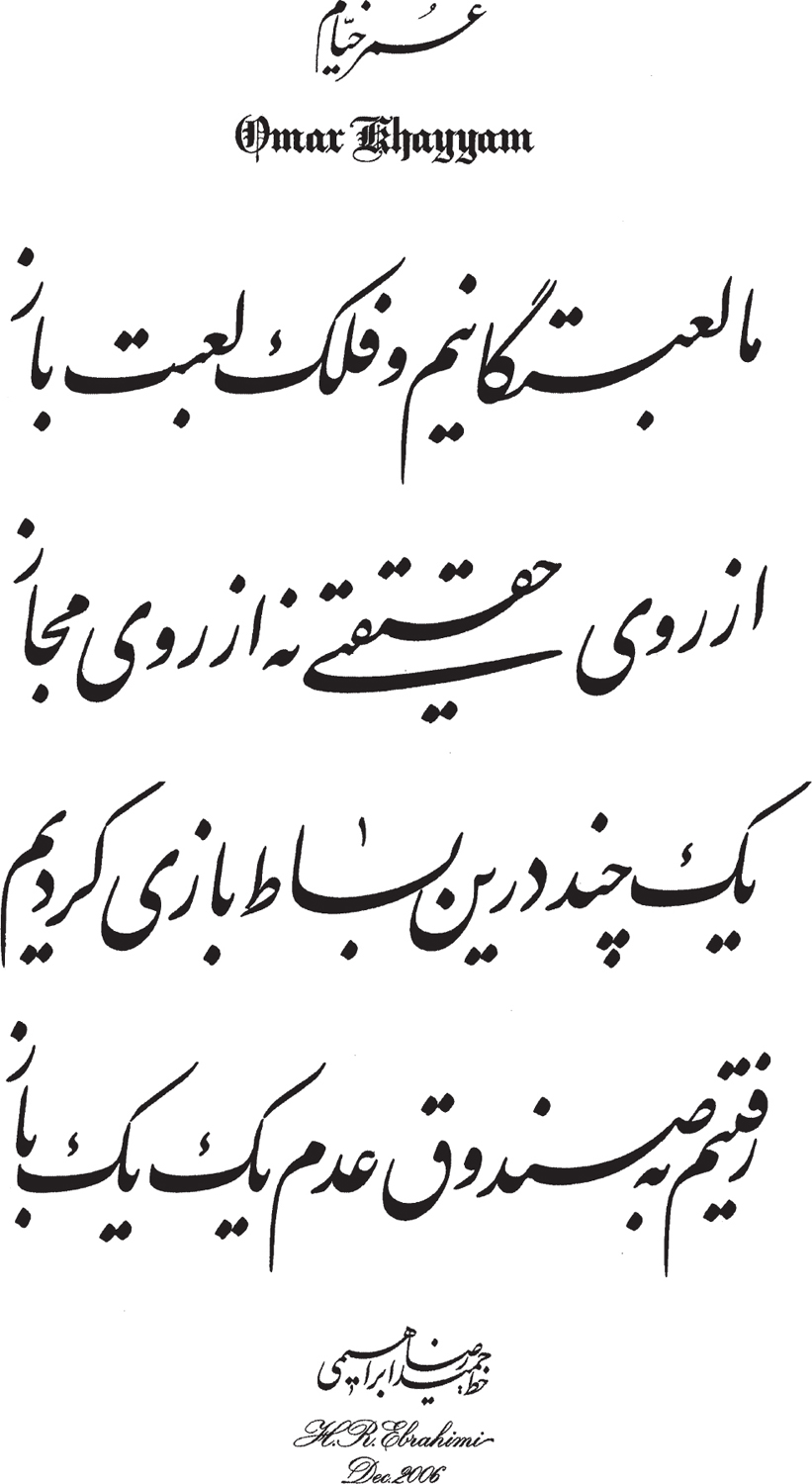

We are the puppets and the firmament is the puppet master,

In actual fact and not as a metaphor;

For a time we acted on this stage,

We went back one by one into the box of oblivion.

Early twelfth century, Persia.

For A&B&37

Frontline Books, London

The Ismaili Assassins

This edition published in 2008 by Frontline Books, an imprint of Pen and Sword Books Ltd, 47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS www.frontline-books.com

Copyright James Waterson, 2008

Foreword David Morgan, 2008

ISBN: 978-1-84832-505-0

eISBN: 9781783461509

The right of James Waterson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library and the Library of Congress

For more information on our books, please visit

www.frontline-books.com, email info@frontline-books.com

or write to us at the above address.

Typeset and designed by JCS Publishing Services Ltd,

www.jcs-publishing.co.uk

Maps drawn by Red Lion Maps

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Kings Lynn

C ONTENTS

M APS AND I LLUSTRATIONS

M APS

I LLUSTRATIONS (C OLOUR )

1 Bukhara, which was sacked in 1220 by Chinggis Khan

2 Isfahan main mosque compound

3 The classic novel Alamut by Vladimir Bartol

4 The caliph before Hulegu

5 Rustam slaying the White Div

6 Ala al-Din Muhammad drugging his disciples

7 The garden of the Old Man of the Mountain

8 The siege of a Turanian stronghold

9 Bird-shaped vessel, twelfth century

10 The Prophet enthroned and four orthodox caliphs

11 Kay Kavus and Kay Khusraw approach the Fire Temple

12 A Sufi riding a leopard, from a copy of the Bustan

13 Hulegu above the gates of Alamut after its surender

14 An iwan of the city of Qazvins main mosque

15 The mausoleum of Sultan Sanjar

16 The Assassins in modern culture

I LLUSTRATIONS (B LACK AND W HITE )

1 Jerusalem, which fell to Saladin in 1187

2 Founder and first master of the Assassins, Hasan-i-Sabbah

3 Famous mathematician and poet, Omar Khayyam

4 The tomb of Saladin

5 Sufis from the late Ottoman Empire

6 The Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem

7 The citadel of Aleppo

8 The minaret of Aleppos Great Mosque

9 The gateway of Aleppos citadel

10 The minbar of the Sunni champion Nur al-Din

11 The minaret of the Great Mosque in Mosul

12 The Mosque of the Barber in Kairouan

13 The Great Mosque of Mecca with the Kaaba

14 The Kaaba in Mecca

15 The great college mosque of al-Azhar

16 The Syrian Assassin castle of Maysaf

17 The forbidding nature of the Elburz Mountains

18 The murder of Nizam al-Mulk in 1092

19 The courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A S A HISTORY WRITER I am totally indebted to the historians who have done so much to make the source materials available to we more linguistically challenged mortals. On a more personal level I would like to give thanks both to Dr David Morgan for introducing me, as an undergraduate, to the Assassins, Saljuqs and Mongols and to Dr Michael Brett for his lectures on the Fatimids and the Crusades period.the Assassins, Saljuqs and Mongols and to Dr Michael Brett for his lectures on the Fatimids and the Crusades period.the Assassins, Saljuqs and Mongols and to Dr Michael Brett for his lectures on the Fatimids and the Crusades period.the Assassins, Saljuqs and Mongols and to Dr Michael Brett for his lectures on the Fatimids and the Crusades period.

I would also like to thank Dr Abbas Khosravi and Mr Hamid Reza Ebrahimi for their superbly skilled calligraphy for the books frontispiece that has brought Omar Khayyams poem to life in the original Farsi.

One final thank you goes to Dr Brian Williams, formerly of the School of Oriental and African Studies, for his encouraging response after my first book The Knights of Islam was published. I remember his lectures, during my university years, being both erudite and enthusiastic and stirring a desire in me to bring Islamic history, and in particular the military history of the medieval Middle East, to a wider audience.

Once again I must thank my dear wife, Michele, for her forbearance at having Mongols, Mamluks, Crusaders and Assassins as permanent houseguests for these last two years and as visitors to our life together for far too long.

F OREWORD

O NE OF THE MORE regrettable consequences of the much greater specialisation that characterised the historical profession in the twentieth century was that historians seemed increasingly to be writing only for other professional historians and for a diminishing number even of them. There came a time when the appearance of a book on a best-seller list would be almost enough in itself to destroy its authors scholarly reputation. In the years I have spent teaching the history of the Middle East and Central Asia, both in London and, more recently, in the United States, I have done my best to persuade my students especially graduate students, some of whom would be making careers as historians, and therefore writing history that historical writing does not have to be boring and unreadable in order to qualify as worthwhile.

That time, fortunately, seems to have passed: no one has any doubts about the scholarly credentials of, say, Simon Schama, despite his various television series and the number of people who buy his books. There is, at last, an increasing awareness of the fact that there is a large reading public that is interested in being offered history that, on the one hand, is well researched and has something significant to say; and on the other, is written in jargon-free English that it is actually a pleasure to read. The historiography of the medieval Islamic sect known (in the West) as the Assassins (more properly the Nizari Ismailis) offers examples of both tendencies.

For a number of years, the standard book in English was Marshall Hodgsons The Order of Assassins (1955). That this was and is a work of value, no one would deny indeed, it was reprinted in paperback as recently as 2005. And Hodgson, who died very prematurely in 1968, was a strikingly original historian whose posthumously published three-volume The Venture of Islam is, among surveys of Islamic history, quite unparalleled as an intellectual tour de force. Even his greatest admirers, however (of whom I am one), could not convincingly argue that he was a master of the English language. He is more than worth the effort: but it is indisputably an effort. A marked contrast came in 1967 with the publication of Bernard Lewiss The Assassins: A Radical Sect in Islam . Lewis has not only been, over a long career, a very prolific historian of the Middle East: he has also written about it more accessibly and readably than any other scholar writing in English in the twentieth century. The Assassins is a good example of Lewis at his best. When it appeared it was the ideal introduction to the subject. Even after forty years it remains well worth reading, whatever advances in research may have taken place since then. Today, a scholar would go first to books by such historians as Farhad Daftary of the Institute of Ismaili Studies. But Lewis is, deservedly, still in print (now with a new 2002 introduction, in which he very justly expresses serious reservations about the notion that there is any kind of terroristic continuity between the Assassins and al-Qaida).