Preface

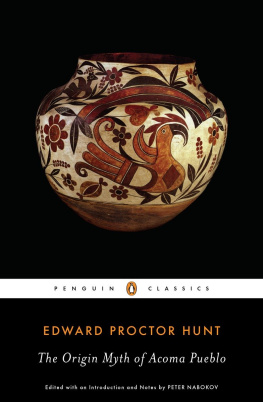

This version of the creation and migration story of Acoma Pueblo in western New Mexico was told in Washington, DC, to scholars at the Smithsonian Institutions Bureau of American Ethnology in the fall of 1928. Its narrator was a sixty-seven-year-old Indian man originally from Acoma Pueblo. His native name was Gaire, meaning Day Break, but the name he acquired at Albuquerque Indian School was Edward Proctor Hunt. Translating for him was a son, Henry Wayne Wolf Robe Hunt, while a younger son, Wilbert Edward Blue Sky Eagle Hunt, assisted with translating the songs that were integral to the myth. In addition, there were Mr. Hunts wife, Marie Morning Star Valle Hunt, and Philip Silvertongue Sanchez, originally from Santa Ana Pueblo. Transcribing the myth were archaeologist and recently appointed chief of the Bureau of American Ethnology Dr. Matthew W. Stirling and a young visiting British anthropologist, Dr. C. Daryll Forde.

After fourteen years of additional editing by some of the American Southwests most respected researchersLeslie A. White, Elsie Clews Parsons, and Franz Boasthe narrative was published in 1942 by the U.S. Government Printing Office as Bulletin 135 of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Origin Myth of Acoma and Other Records. In its preface, the narrator and assistants were not named; Stirling was the author of record.

Over the years, this relatively obscure publication became one of the most cited sources on Pueblo Indian worldview and narrative tradition. Students of mythology, Pueblo culture, and the region quoted from it, wove it into their theories, and incorporated it into anthologies, interpretations of Pueblo history and society, and university courses on myth and oral tradition. A newly edited version that reinserted material that had been excised, offered a biographical profile of its narrator and his assistants, and rendered the text more accessible, seemed overdue.

First and foremost, I am grateful to the late Wilbert Hunt for background on his father, for memories of his familys travels and their time in Washington, and for his blessing to prepare this edition of his fathers version. Second, I am indebted to the late James Glenn, archivist at the Smithsonians National Anthropological Archives, who showed me the Frances Densmore and Wolf Robe Hunt files that confirmed Edward Hunt as the narrator and began my research into his family. Mary Powell and Marta Weigle of Ancient City Press had published my work on Acomas architecture, derived from the 1934 Historic American Buildings Survey Project, and encouraged this republication. For time and resources to research the myths background, edit its text, and investigate the familys background, I thank Princeton University for a fall 2006 Stewart Fellowship, Pasadenas Huntington Library for a 200708 residency Mellon Fellowship, the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation for a 200809 fellowship, UCLAs Faculty Grants Program, and New Mexicos State Records Center and Archives grant program.

I am also indebted to the American Philosophical Society, the Smithsonian Institutions National Anthropological Archives, Ann Arbors University of Michigan Special Collections Library, Pasadenas Southwest Museum, and the University of New Mexicos Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections for access to materials directly related to the history behind this publication and the careers of the Hunt family.

Individuals who have been essential to my work on this publication are Susan Bergholz, Alfred Bush, Don Cosentino, Linda Feldman, Karen Finney, Jim Glenn, Louis Hieb, Eddie Hunt, Steve Karr, Paul Kroskrity, Robert Leopold, Jay Miller, Alfonso Ortiz, Mo Palmer, Bill Peace, Patrick Polk, Roy Ritchie, Gregory Schachner, Bill Truettner, Ken Wade, and Kim Walters.

Introduction

THE CREATION OF CREATION MYTHS

Stories about the origins of any communitys universeits gods, spirits, heroes, and landscapes; its beginnings, wanderings, sufferings, and fulfillmentsare the most important accounts any society can tell itself about itself. They are its divine charter, declaration of independence, constitution, and bill of rights all wrapped into one guiding narrative. Like a cosmic compass, they set its course. They provide models for its institutions and remind its people who they are, why they exist, and how they fit into their grand scheme of things. As foundational narratives, these stories are sometimes dramatized, usually for members only and at regular moments on the communitys ceremonial calendar. They are also recalled as scripts or formulas for conducting proper rituals. And they can be revisited whenever their teachings seem most relevant.

CLASSICS

CLASSICS