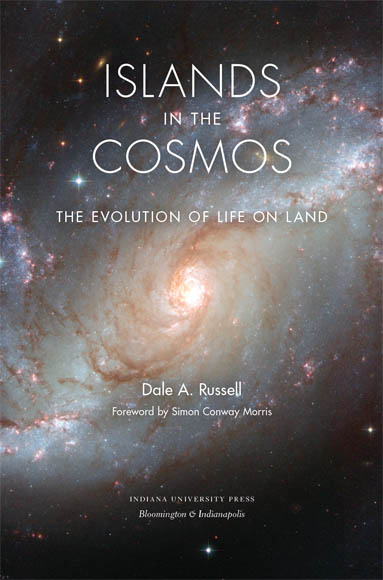

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

601 North Morton Street

Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA

http://iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

Orders by e-mail

2009 by Dale A. Russell

Foreword 2009 by Simon Conway Morris

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Manufactured in China

Russell, Dale A.

Islands in the cosmos : the evolution of life on land / Dale A. Russell ; foreword by Simon Conway Morris.

p. cm. (Life of the past)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-35273-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Evolution (Biology) 2. LifeOrigin. 3. Biotic communities. 4. Natural selection. 5. Paleoecology. 6. PaleontologyMesozoic. I. Title.

QH366.2.R87 2009

576.8dc22

2008055797

1 2 3 4 5 14 13 12 11 10 09

For my wife, Janice, our families, and our childrens families

my universe

CONTENTS

by Simon Conway Morris

FOREWORD

In his famous closing passage in On the Origin of Species Charles Darwin felt moved to write of how his theory might well explain the diversity and fecundity of life, but for him at least, it still invoked a sense of grandeur. Darwinism remains the air all evolutionary biologists breathe, but so too very many of us see in the history of life an almost epic quality: abysses of time, strange and outlandish denizens, unsolved mysteries, vanished worlds. Unsurprisingly this can lead to a tension. After all, in their day-to-day work paleontologists need to be like any other scientist: prosaic, hard-headed, and objective. But behind this, too often unsung, lies inspiration, imagination, and a sense of wonder. Two apparently separate worlds seem to lie ever further apart: the book of poetry lies unopened beside the electron microscopebut not always, and not necessarily. In this book they are reunited in a sweeping and thrilling overview of the ancient past.

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there. L. P. Hartleys well-known words are strangely apposite to this book, as they provide a leitmotif for a journey not only toward irrevocably lost worlds, but ones that are discomfortably unfamiliar, brooding, almost alien. Eschewing the worthy but tired dioramas that used to bedeck the walls of natural history museums and that punctuate the books of instruction, ones populated with shuffling trilobites and puzzled-looking brontosaurs, Dale Russell flings open a series of windows into the worlds of the past. It is an open and generous invitation, unafraid of employing vivid imagery and lyrical phrases. Whether it be to visit the earliest Earth, where he describes emergent fields of semiconsolidated lava rubble... punctuated here and there by steaming springs exhaling sterility [and] far into the distance, squat volcanoes might barely be distinguished, projecting from a cold leaden sea along the limb of a blue-gray horizon, or what was in geologic time almost yesterday, where together we can stalk through a dinosaur graveyard. But now the usual trope of bleached bones and grinning skulls is turned into something more fertile, but also more macabre. Here each gigantic corpse serves as a biological oasis, teeming with life, but from which also wafts the unmistakable stench of mortal decay.

Again and again Dale Russell combines the familiar with the unexpected, and to good effect. Ancient scenes are dotted with plants and traversed by great rivers, while beyond the horizon lie vast deserts that dwarf the Sahara and immense mountains that overshadow the Himalayas. But there is always a haunting undertone, because while Dale Russell brings to life these dead communities, at the same time he repeatedly emphasizes their archaic nature. And this he does in two intriguingly different ways. First, even in some living biomes, we find more than echoes of those distant worlds, a departing drumroll of former monsters, a flutelike threnody of extinct organic arabesques. Second, and even more intriguing, is the overwhelming sense that these worlds were not only different, but disorientingly so. Here are realms of silence populated by expressionless eyes, where any memories would exist solely as the repositories of the charnel house, of dust and decay, embalmed in the smell of aromatic resins. For us humans they would have been lonely and infertile places, not locations to linger. Now, paradoxically, they are places to relish when viewed through the spectacles of scientific understanding and when molded by our unique gifts of imagination.

Yet however remote these worlds might be, they were a product of evolution, as of course are we. From our privileged perspective, we see them as pregnant with possibilities, a planet that slowly awakens as the first minds begin to stir. Here, surely, is a saga that is even today incompletely told: awareness flickers into existence and intelligences emerge, culminating in the incredible trajectory of human evolution. Dale Russell is surely correct when he proclaims that ours is a truly special time. And as I do, he insists that within the evolutionary tapestry, there are woven inevitabilities, and here perhaps we begin to depart from one part of the present-day neo-Darwinian consensus. This is because a central tenet of neo-Darwinism is its open-endedness and indeterminacy, famously captured by Stephen Jay Goulds insistence that were we to rerun the tape of life, then the outcome would be totally different. But this is flatly contradicted by what we know as evolutionary convergencethe manner in which unrelated organisms repeatedly arrive at the same solution. Perhaps this is best known by the striking similarity between our eye and that of an octopus; each evolved independently into what is very close to an optimal end point. This, along with innumerable other examples, is one line of evidence that evolution is actually reading an instruction manual to which we have by no means yet gained full access. Birds, for example, evolved from the dromaeosaurian dinosaurs, and we see the evidence before our eyes, in the form of Archaeopteryx; but much less well known is that two other lineages were going in much the same direction. Birds are inevitable, and so most likely are mammalsas well as, I would argue, are humans.

These inevitabilities not only provide a compass to the Darwinian adventure, but also in revealing directionalities allow us to reconsider the concept of evolutionary progress, not as an artifact of human wish fulfillment but as integral to this tapestry of life. And Dale Russell brilliantly captures this sense by a dramatic retelling of von Baers hypothesis whereby the egg, say of a reptile, hurtles through its equivalent evolutionary history, achieving in a few months what it took billions of years for evolution to achieve. Yes, yes, nod the heads of some world-weary embryologists, that is what happens, but in a few deft strokes, Dale Russell has managed to reignite our sense of wonder: embryology, and indeed all life,

Next page