Contents

Guide

ISONOMIA

and the

ORIGINS OF PHILOSOPHY

KJIN KARATANI

Translated by Joseph A. Murphy

DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS Durham and London 2017

TETSUGAKU NO KIGEN

BY KJIN KARATANI

2012 by Kjin Karatani

Originally published 2012 by Iwanami Shoten, Publishers, Tokyo

This English edition published 2017 by Duke University Press, Durham, NC, by arrangement with the proprietor c/o Iwanami Shoten, Publishers, Tokyo.

2017 Duke University Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

Designed by Matthew Tauch

Typeset in Scala by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Karatani, Kjin, 1941 author.

Title: Isonomia and the origins of philosophy / Kjin Karatani ; translated by Joseph A. Murphy.

Other titles: Tetsugaku no kigen.

English Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017004990 (print) | LCCN 2017011334 (ebook)

ISBN 9780822368854 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780822369134 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 9780822372714 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH : Philosophy, Ancient.

Classification: LCC B 115. J 3 K 3713 2017 (print) | LCC B 115. J 3 (ebook) | DDC 180dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017004990

Contents

This translation is based on the fourth edition of Tetsugaku no kigen (Iwanami Shoten, 2012). The text incorporates extensive quotation from Greek, German, Japanese, French, and Chinese sources. Where available, accepted English-language translations have been used. Where not available, translations have been adapted from web-based sources, or translated from the original, as indicated in the citations. I would like to acknowledge the advice and assistance I received from the authors wife, Lynne Karatani, which has been instrumental to the projects readability.

Map of the Ionian and Aegean Sea Region

In the process of writing my last work, Sekaishi no kz (Iwanami Shoten, 2010; translated as The Structure of World History , Duke University Press, 2014), it occurred to me that I should give more detailed consideration to ancient Greece. However, considering the overall balance of the work, it seemed better advised to place these thoughts in a new volume. This book is the result. Consequently, it takes the theoretical framework presented in The Structure of World History as a premise. Still, even without that knowledge, this book should be easy enough to follow. To be on the safe side, though, I have included a summary of the argument of The Structure of World History and notes on how that corresponds to this book, as an appendix called From The Structure of World History to Isonomia and the Origins of Philosophy . In points where the argument of this book is unclear, please refer to this text.

The first version of this book was serialized in the monthly journal Shinch , to whose chief editor, Yutaka Yano, I owe a great debt. Without his support, this work would never have come to fruition. I am similarly indebted to the editor of this book, Kiyoshi Kojima, from Iwanami Shoten.

KJIN KARATANISEPTEMBER 15, 2012 BEIJING

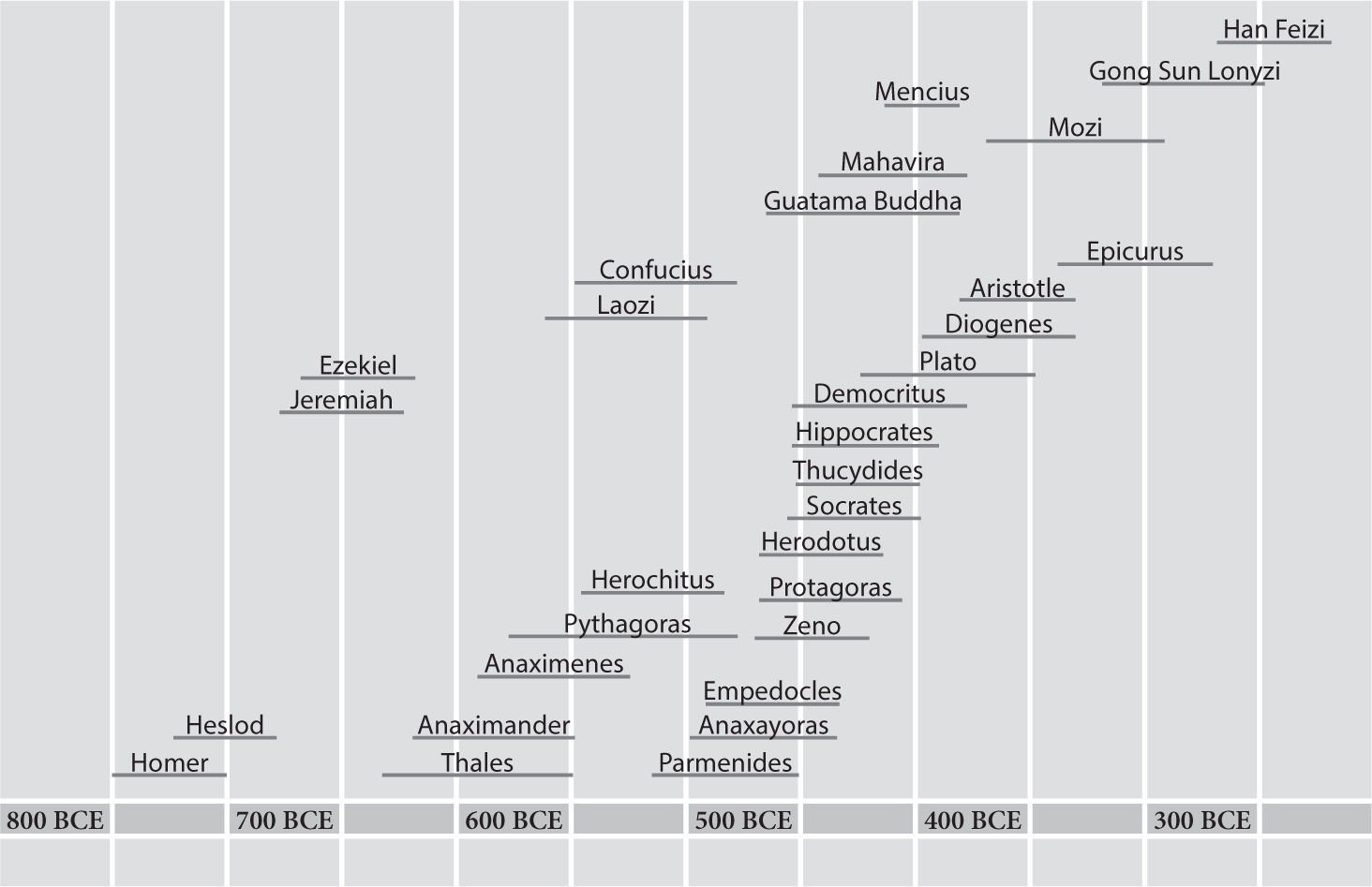

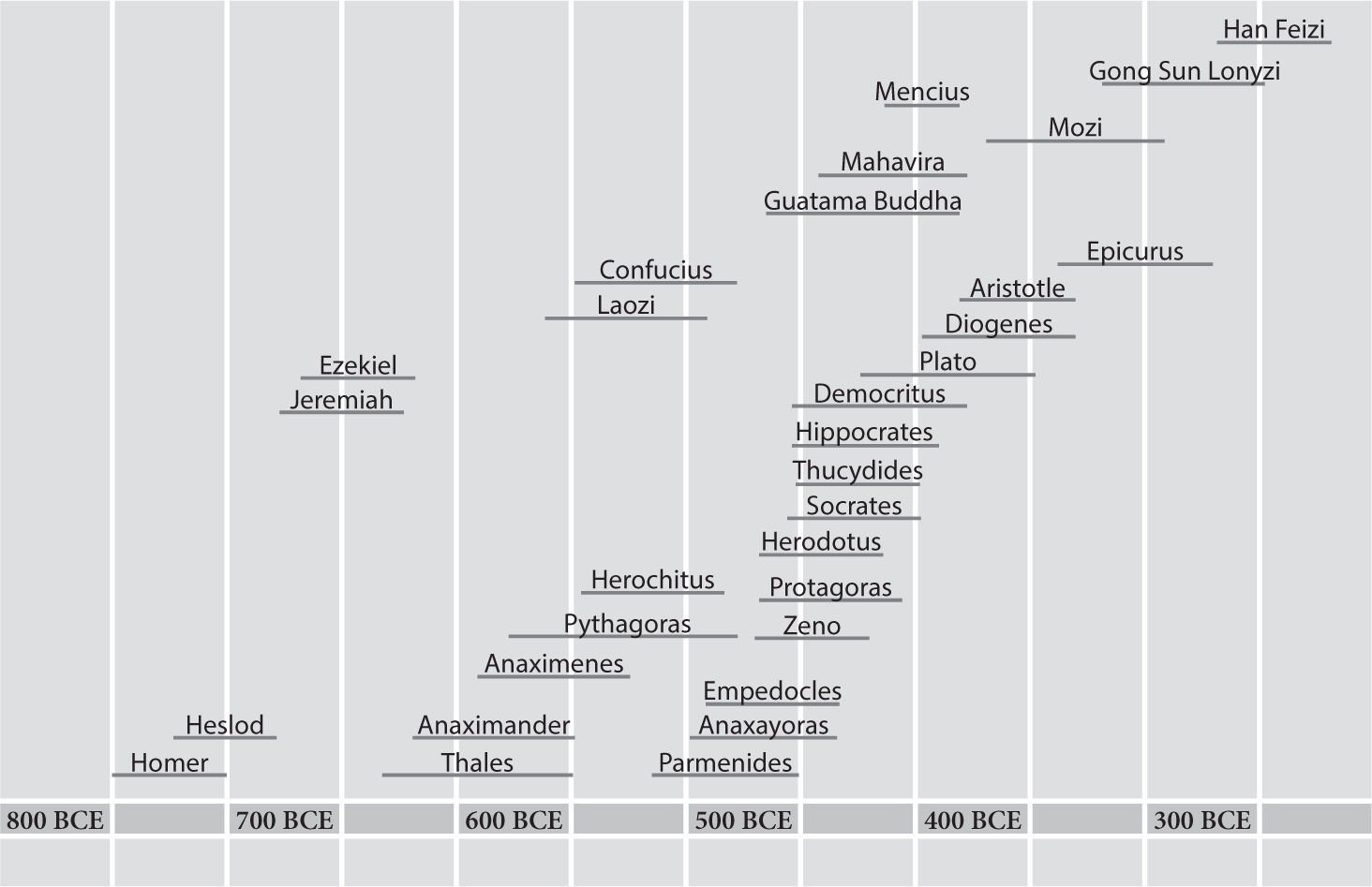

FIGURE INTRO.Chronology of Ancient Greek and Asian Thinkers

Around the sixth century BCE , Ezekiel and the biblical prophets emerged from among exiles in Babylon; Thales emerged in Ionia on the coast of Asia Minor; Gautama Buddha and the Jain founder Mahavira appeared in India; and Laozi and Confucius emerged in China. This simultaneity and parallelism are striking and cannot be explained straightforwardly based on socioeconomic history. As an example, Marxists typically see philosophy and religion as parts of an ideological superstructure, itself determined by the economic base, by which is meant the modes of production. However, attention to transformations of the economic base has not proven sufficient to explain the overall dramatic transformations of this period.

Consequently, a perspective that would explain the transformations of this period as a revolution or evolution of spirit taking place at the level of the ideological superstructure became dominant. This view is best represented by Henri Bergsons The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (1932). According to Bergson, human society started as a small closed society, and morality developed out of it for its benefit. If so, what might have transpired for it to become open? It is clear that in the time leading up to the sixth century BCE , human society was evolving at multiple locations from clan society to world empire, where diverse peoples interact on the basis of trade. But this by itself is not sufficient to bring about an open society. For Bergson, Never shall we pass from the closed society to the open society, from state to humanity, by any mere broadening out. The two things are not of the same essence. these transformations at the level of religion. According to him, religion in a closed society is static, while religion in an open society is dynamic. The leap from static religion to dynamic religion is brought about by the individual of privilege. Bergson argues that elan damour , or an impetus of love, is at the basis of the evolutionary transformations, and manifests itself through the actions of these individuals of privilege.

However, we need not, and should not, appeal to this kind of theoretical leap. I acknowledge that the leap from a closed society to an open society occurred on the level of religion. Having said that, this fact itself can be traced to the economic base, in my opinion, on the condition that we understand the economic base in terms of modes of exchange, instead of the Marxists usual modes of production. For example, the development of religionfrom animism, to magic, to world religion, finally to universal religionfalls out neatly when understood in terms of transformation in the modes of exchange.

Normally, the term exchange implies commodity exchange. I refer to this as mode of exchange C. This arises when exchange occurs between one community and another, not in exchange internal to a community or family. What occurs in the latter is reciprocity in the form of the gift and repayment, which is mode of exchange A. There is a further type of exchange, different from both, called mode of exchange B. This is an exchange between the ruler and the ruled, which at first glance does not appear to be a kind of exchange. However, if the ruled, in offering obedience to the ruler, receives protection and security in return, this too is an exchange. The state has its roots in this mode of exchange B.

The historical transformations of religion can be tracked in terms of these changes in the mode of exchange. For example, in animism, all things in the world are each thought to possess an anima (or spirit). Because of this, a person cannot associate with an object without first putting its anima under control. For example, a person cannot take an animal in hunting without this accommodation to the anima. In this case, the person despiritualizes and objectifies the anima, first by means of making an offering to it and imposing debt on it. This is what is called sacrifice. Burial and funeral rites, as well, accommodate the anima of the dead person through an offering. Magic, too, is a mechanism of this kind of exchange, based on gift giving. It is about putting nature under the magicians control by making it into an inanimate object by means of a gift to its anima. If understood in this way, magicians, who see nature as an object, can be regarded as the first scientific thinkers.