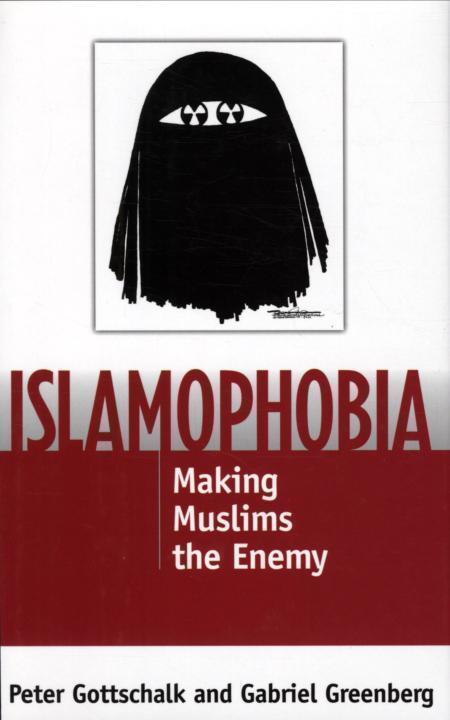

Making Muslims the Enemy

Peter Gottschalk and Gabriel Greenberg

Peter Gottschalk dedicates this book to Ari, my daughter and inspiration.

ix

The seed for this book was sown in a slide lecture by professor John Woods at the University of Chicago. Inspired by Sam Keens Faces of the Enemy, this lecture discussed the portrayal of Muslims and Islam in American political cartoons. Peter, in the audience as a graduate student, left motivated to include political cartoons in his own classes once he began to teach. When he did, it helped inform the interest of Gabriel, who investigated the topic in his senior honors thesis. For both, Keen's book provided useful insights and illustrative examples for their own research.

Both authors are indebted to Wesleyan University, which provided funds to defray the copyright costs of publishing the cartoons included in the volume. Special thanks go to Dean I)on Moon for his unwavering support. We also acknowledge the important insights contributed by nienibers of the Wesleyan University community to this project during its formative stages, especially Bruce Masters. Both of us are under a great debt of obligation to Rhonda Kissinger and, especially, Millie Hunter, who worked so hard tracking down and obtaining the permissions necessary for the volume, and Allyn Wilkinson and Kendall Hobbs for their help with the cartoons. Beyond Wesleyan, we appreciate Carl Ernst for his comments, Bruce Lawrence for his insights, and John Esposito for his support.

Gabriel would personally like to offer thanks to his family and his professors at Wesleyan, especially Vijay Pinch, who prodded me toward a love of history and knowing; Vera Schwarcz for her compassionate approach to understanding; and Peter Gottschalk, who inspired this work through his commitment to revealing to us what it is we think. Peter has much to teach about tolerance and coexistence, and I am a proud (yet work-in-progress) product of that education.

Peter would like to acknowledge his father, Rudolf Gottschalk, and his friend Phil Hopkins for their invaluable and insightful editorial comments and suggestions. Shannon Winnubst deserves particular thanks for her encouragement to pursue this project. I also appreciate the insights offered by faculty and students at Wesleyan University and Southwestern University with whom I have had the privilege of sharing my thoughts on these matters and who prove the adage that we are all teachers of one another. Of course, Gabe Greenberg deserves my deepest appreciation for working with me. This book results directly from his interest, which nurtured the nascent project; his research, which established its historical roots; and his outstanding writing and editing, which brought it to fruition. Finally, and always first, I acknowledge the inestimable support of my mother and the rest of my family during the difficult days of this work's composition, and the exuberant presence of my daughter, An, in my life and work: Writing remains lifeless without love.

7,J he controversy regarding the Danish publication of editorial cartoons negatively depicting the Prophet Muhammad rages outside our walls even as we prepare this book for publication. Not only does the unfortunately fatal conflict demonstrate the dynamics we identify as Islamophobia, it also demonstrates the seriousness with which political cartoons can be taken.

The issue originated with twelve depictions of the Prophet Muhammad commissioned by the culture editor of the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posted. He had noticed a hesitancy among Europeans in their portrayals of A Dutch Muslim, offended by the images published in September 2005, sought redress from the newspaper and the government but found none. At his prompting, eleven ambassadors of Muslimmajority nations asked for a meeting with the government, which turned down their request. He then turned to the scholars of al-Azhar University in Cairo and the secretary general of the Arab League in Lebanon, who condemned the images.'- Finally, awareness of the cartoons became widespread after they made the rounds at an Islamic conference in Mecca.' A global protest soon grew, typified by peaceful gatherings of thousands of protestors in many places but overshadowed by violence in Damascus, Beirut, Tehran, Kabul, Lahore, and Benghazi.

Once more the familiar pattern had unfolded, as some Muslims reacted violently to an apparently insignificant event that seemed the latest battlefront in the West's holding action to preserve inalienable rights against ever-threatening Islamic intolerance. Although the Muslims involved never represented more than a fraction of a fraction of the world's more than one billion Muslims, their vociferous fury only confirmed a Western image of Muslim intolerance and Islamic otherness. The media's consistent disinterest in nonviolent Muslim perspectives hardened this view. The perception of this conclusion, already familiar to many Muslims in the West and elsewhere, alienates ever more Muslims. Where the spiral ends, no one knows-but it doesn't appear promising.

This particular controversy perfectly illuminates the multiple aspects of these larger issues. The widespread puzzlement among non-Muslim Americans about the sharp responses reflects how little they understand Muslims. The breadth of Muslim response demonstrates both a heightened sensitivity to Western denigration of Islam and an increasing sense that the West seeks a war against Muslims through either constant deprecation, as in the cartoon controversy, or outright conquest, as in Afghanistan and Iraq. All of this turns wildly on the fulcrum of asymmetrical power. Muslims in the West and elsewhere know that now, as has been the case since the era when European imperialists ruled over most Muslims, what they think about Christians has far fewer consequences than what Westerners think about Muslims. With each passing skirmish, Muslims characterize these Western thoughts as Islamophobia. Simultaneously, the predominantly Christian and/or secular populations of the West do not appreciate that their attitudes toward Islam both presume the norms of Christianity and secularism and negatively reflect centuries of religious and political conflict around the world.

Ultimately, very few on either side wish to pick a fight. Yet the distance between the various perspectives involved allows some to opportunistically manipulate Islamophobia for their own advancement. The Danish editor, disagreeing with the hesitancy of some Europeans to offend, deliberately defied Muslim sensitivities. The Syrian government doubtlessly allowed, and in fact may have promoted, the burning of the Danish and Norwegian embassies to serve its own political ends. Sadly, dozens of people have died because of the agitations, while political fissures and social stereotypes have deepened.