Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

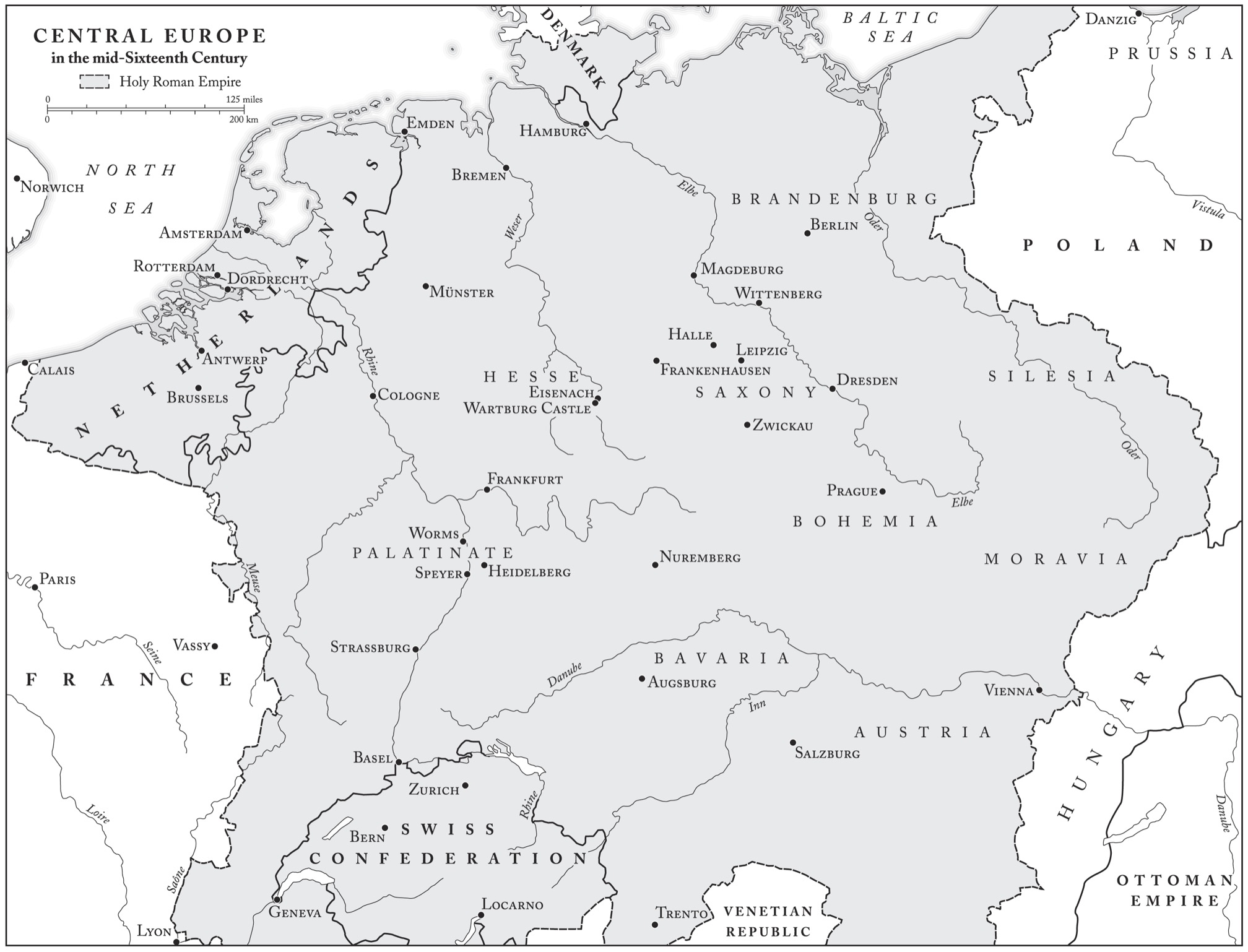

Map drawn by Martin Brown. Used by permission of William Collins, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers (UK).

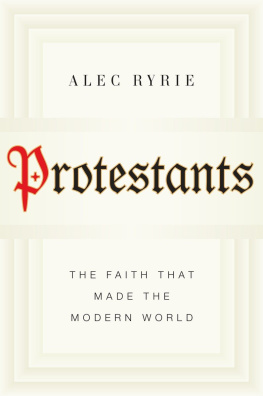

Introduction

I n 1524, Erasmus of Rotterdam wrote a blistering attack on a fanatical new cult that was spreading across northern Europe like a plague. These people claim to be preaching the Bibles pure message, he said, but look at how they actually use the Bible, twisting it to mean whatever they want:

They are like young men who love a girl so immoderately that they imagine they see their beloved wherever they turn, or, a much better example, like two combatants who, in the heat of a quarrel, turn whatever is at hand into a missile, whether it be a jug or a dish.

This book is about that cult and how it became one of the most creative and disruptive movements in human history. At present, about one-eighth of the human race belongs to it, and it has decisively shaped the world in which the other seven-eighths live. My aim is to convince you that we cannot understand the modern age without understanding the dynamic history of Protestant Christianity.

It turns out that Erasmus was right: Protestants are fighters and lovers. They will argue with anyone about almost anything. Some of these arguments are abstruse, others brutally practical. If we look at the great ideological battles of the past half millenniumfor and against toleration, slavery, imperialism, fascism, or Communismwe will find Protestant Christians on both sides.

But Protestants are also lovers. From the beginning, a love affair with God has been at the heart of their faith. Like all long love affairs, it has gone through many phases, from early passion through companionable marriage and sometimes strained coexistence, to rekindled ardor. Beneath all the arguments, the distinguishing mark of a Protestant is the feeling and memory of that love, one on which no church or human authority can intrude. It is because Protestants care so deeply about God that they have been willing both to fight one another and take on the world on his behalf.

So this is both an interior and an exterior story, a spiritual and emotional drama with practical and political implications. The spirituality at Protestantisms center sends out waves that sometimes crest into tsunamis as they encounter the ordinary stuff of human life. This book will tell the stories of the changes they have left in their wake. Protestants have faced down tyrants, demanded political participation, advocated tolerance, and valued the individual. Equally, they have insisted on God-given inequality, valorized state power, persecuted dissenters, and placed the community above its members. They have fought religious wars against each other and have turned secular struggles into crusades. Some have tried to withdraw from the secular world and its politics altogether, and at times they have been the most revolutionary of all.

The Protestant Reformation was clearly an important event in world history, but that does not mean that it can take the credit or the blame for everything that has happened since. Nor does it make Martin Luther a prophet of individualism or a hero of self-determination. He and the Protestants who succeeded him were not trying to modernize the world, but to save it. And yet in the process they profoundly changed how we think about ourselves, our society, and our relationship with God. This book tells the story of that transformation: a story, in outline, of how three of the key ingredients of the world we live in are rooted in Protestant Christianity.

The first is free inquiry. Protestants stumbled into this slowly and reluctantly, but Luthers bedrock principles led inexorably in that direction. The insistence that all human authority in religious matters is provisional, and that the human conscience, constrained only by the Bible and the Holy Spirit, is ultimately sovereign, means that Protestants who try to police the boundaries of acceptable argument have in the end always failed. Protestants have always been divided among themselves both in their religious and in their political leadership, making it easy for new and dissenting ideas to find spaces both at home and across borders.

Protestantism is not a paradise of free speech, but an open-ended, ill-disciplined argument. How it has come to continuously generate new ideas, and revive old ones, is a recurring theme of this book. Protestants bare-knuckle style of public debate wore down print censorship, and Protestant universities and scholars led the way in the emergence of the new natural sciences in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Slowly and reluctantly, one notion which a few radical Protestants put aboutthat religious difference and free speech ought to be accepted as matters of principle, rather than merely tolerated as unavoidable necessitiesbecame a new orthodoxy.

This is linked to Protestantisms second, more dangerous contribution: its tendency toward what we are compelled to call democracy. Virtually all Protestants before the nineteenth century, and many since, regarded that word with horror, yet the undertow was there. Protestants regularly found themselves having to deal with governments that did not share their beliefs. They asserted not a right to choose their rulers but a solemn duty and responsibility to challenge them. In performing that duty, the Scottish radical John Knox wrote in 1558, all man is equal. Few Protestants at the time agreed, and even Knox meant something very different from what we understand equality to mean today. Most early Protestants favored monarchy, order, and social stability. But their rulers had an intolerable tendency to act in defiance of Gods will, and so, again and again, they were forced reluctantly to take matters into their own hands. This is what we should expect from consciences fired with love for God and ready to take on all comers.

Left to itself, this could lead to revolution or to the creation of self-righteous theocracies, and as we shall see, both have repeatedly happened. But these impulses have been tempered by the third, much less remarked-upon but perhaps more significant, ingredient of Protestantisms modernizing cocktail: its apoliticism. Protestants might have sometimes confronted or overthrown their rulers, but their most constant political demand is simply to be left alone. Returning to Christianitys roots in ancient Rome, they have tried to carve out a spiritual space where political authority does not apply and have insisted that that space, the kingdom of Christ, matters far more than the sordid and ephemeral quarrels of this world. The results are paradoxical. Protestants have often been obedient subjects to thoroughly noxious rulers, taking no interest in politics so long as their own separate sphere was respected. It has also meant that rulers who would not or could not respect that sphere have faced unexpectedly stubborn opposition. In the process, Protestants have helped to give the modern world the strange, counterintuitive notion of limited government: the principle that the first duty even of the most righteous ruler is to respect his subjects freedom and allow them to live their lives as they see fit.