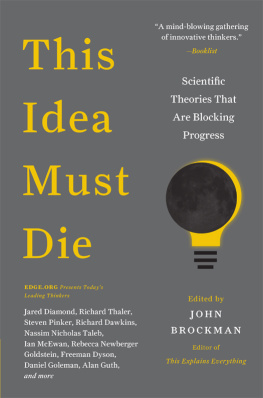

In 1991 I suggested the idea of a third culture, which consists of those scientists and other thinkers in the empirical world who, through their work and expository writing, are taking the place of the traditional intellectual in rendering visible the deeper meanings of our lives, redefining who and what we are. By 1997 the growth of the Internet had allowed implementation of a home for the third culture on the Web, on a site named Edge (www.edge.org).

Edge is a celebration of the ideas of the third culture, an exhibition of this new community of intellectuals in action. They present their work, their ideas, and comment about the work and ideas of third culture thinkers. They do so with the understanding that they are to be challenged. What emerges is rigorous discussion concerning crucial issues of the digital age in a highly charged atmosphere where thinking smart prevails over the anesthesiology of wisdom.

The ideas presented on Edge are speculative; they represent the frontiers in the areas of evolutionary biology, genetics, computer science, neurophysiology, psychology, and physics. Some of the fundamental questions posed are: Where did the universe come from? Where did life come from? Where did the mind come from? Emerging out of the third culture is a new natural philosophy, new ways of understanding physical systems, new ways of thinking about thinking that call into question many of our basic assumptions of who we are, of what it means to be human.

An annual feature of Edge is The World Question Center, which was introduced in 1971 as a conceptual art project by my friend and collaborator the late artist James Lee Byars, who died in Egypt in 1997. I met Byars in 1969, when he sought me out after the publication of my first book, By the Late John Brockman. We were both in the art world, we shared an interest in language, in the uses of the interrogative, and in the SteinsEinstein, Gertrude Stein, Wittgenstein, and Frankenstein. Byars inspired the idea of Edge and is responsible for its motto:

To arrive at the edge of the worlds knowledge, seek out the most complex and interesting minds, put them in a room together, and have them ask each other the questions they are asking themselves.

He believed that to arrive at an axiology of societal knowledge it was pure folly to go to a Widener Library and read 6 million books. (He kept only four books at a time in a box in his minimally furnished room, replacing books as he read them.) His plan was to gather the 100 most brilliant minds in the world together in a room, lock them in, and have them ask each other the questions they were asking themselves. The result was to be a synthesis of all thought. But between idea and execution are many pitfalls. Byars identified his 100 most brilliant minds, called each of them, and asked them what questions they were asking themselves. The result: seventy people hung up on him.

By 1997 the Internet and e-mail had allowed for a serious implementation of Byarss grand design, and this resulted in launching Edge. Among the first contributors were Freeman Dyson and Murray Gell-Mann, two names on his 1971 list of the 100 most brilliant minds in the world.

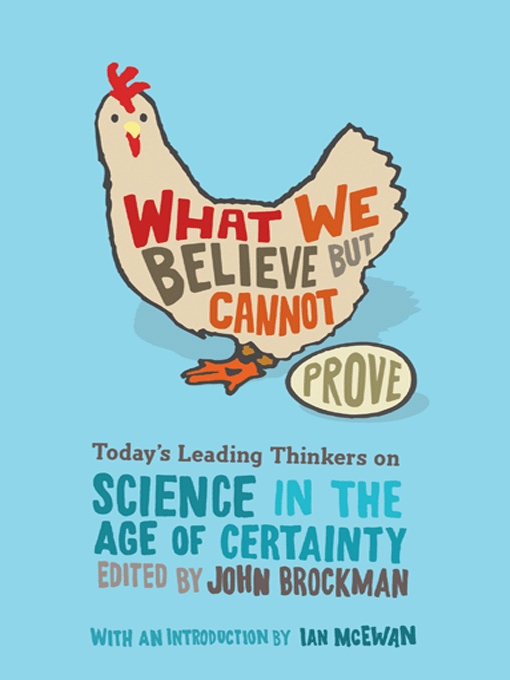

For each of the eight anniversary editions of Edge I have used the interrogative myself and asked contributors for their responses to a question that comes to me, or to one of my correspondents, in the middle of the night. The 2005 Edge Question was suggested by the theoretical psychologist Nicholas Humphrey.

Great minds can sometimes guess the truth before they have either the evidence or arguments for it. (Diderot called it having the esprit de divination.) What do you believe is true, even though you cannot prove it?

The 2005 Edge Question was an eye-opener (BBC 4 Radio characterized it as fantastically stimulatingthe crack cocaine of the thinking world). In the responses gathered here, theres a focus on consciousness, on knowing, on ideas of truth and proof. If pushed to generalize, I would say that these responses form a commentary on how we are dealing with a surfeit of certainty. We are in the age of search culture, in which Google and other search engines are leading us into a future rich with an abundance of correct answers along with an accompanying naive sense of conviction. In the future, we will be able to answer the questionsbut will we be bright enough to ask them?

This book proposes an alternative path. It may be that its OK not to be certain, but to have a hunch and to perceive on that basis. As Richard Dawkins, the British evolutionary biologist and champion of the public understanding of science, noted in an interview following publication of the 2005 Question: It would be entirely wrong to suggest that science is something that knows everything already. Science proceeds by having hunches, by making guesses, by having hypotheses, sometimes inspired by poetic thoughts, by aesthetic thoughts even, and then science goes about trying to demonstrate it experimentally or observationally. And thats the beauty of sciencethat it has this imaginative stage but then it goes on to the proving stage, the demonstrating stage.

There is also evidence in this book that scientists and their intellectual allies are looking beyond their individual fieldsstill engaged in their own areas of interest but, more important, thinking deeply about new understandings of the limits of human knowledge. They are seeing our science and technology not just as a matter of knowing things but as a means of tuning into the deeper questions of who we are and how we know what we know.

I believe that the men and women of the third culture are the preeminent intellectuals of our time. But I cant prove it.

Proof, whether in science, philosophy, criminal court or daily life, is an elastic concept, interestingly beset with all kinds of human weakness, as well as ingenuity. When jealous Othello demands proof that his young wife is deceiving him (when, of course, she is pure), it is not difficult for Iago to give his master exactly what he masochistically craves. For centuries, brilliant Christian scholars demonstrated by rational argument the existence of a sky-god, even while they knew they could permit themselves no other conclusion. The mother wrongly jailed for the murder of her children, on the expert evidence of a pediatrician, reasonably questions the faith of the courts in scientific proof concerning sudden infant death syndrome. When Penelope is uncertain whether the shaggy stranger who turns up in Ithaca really is her husband Ulysses, she devises a proof invoking the construction of their nuptial bed which would satisfy most of us but not many logicians. The precocious ten-year-old mathematician who exults in the proof that the angles of a triangle always add up to 180 degrees will discover before his first shave that in other mathematical schemes this is not always so. Very few of us know how to demonstrate that two plus two equals four in all circumstances. But we hold it to be true, unless we are unlucky enough to live under a political dispensation that requires us to believe the impossible; George Orwell in fiction as well as Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, and various others in fact, have shown us how the answer can be five.