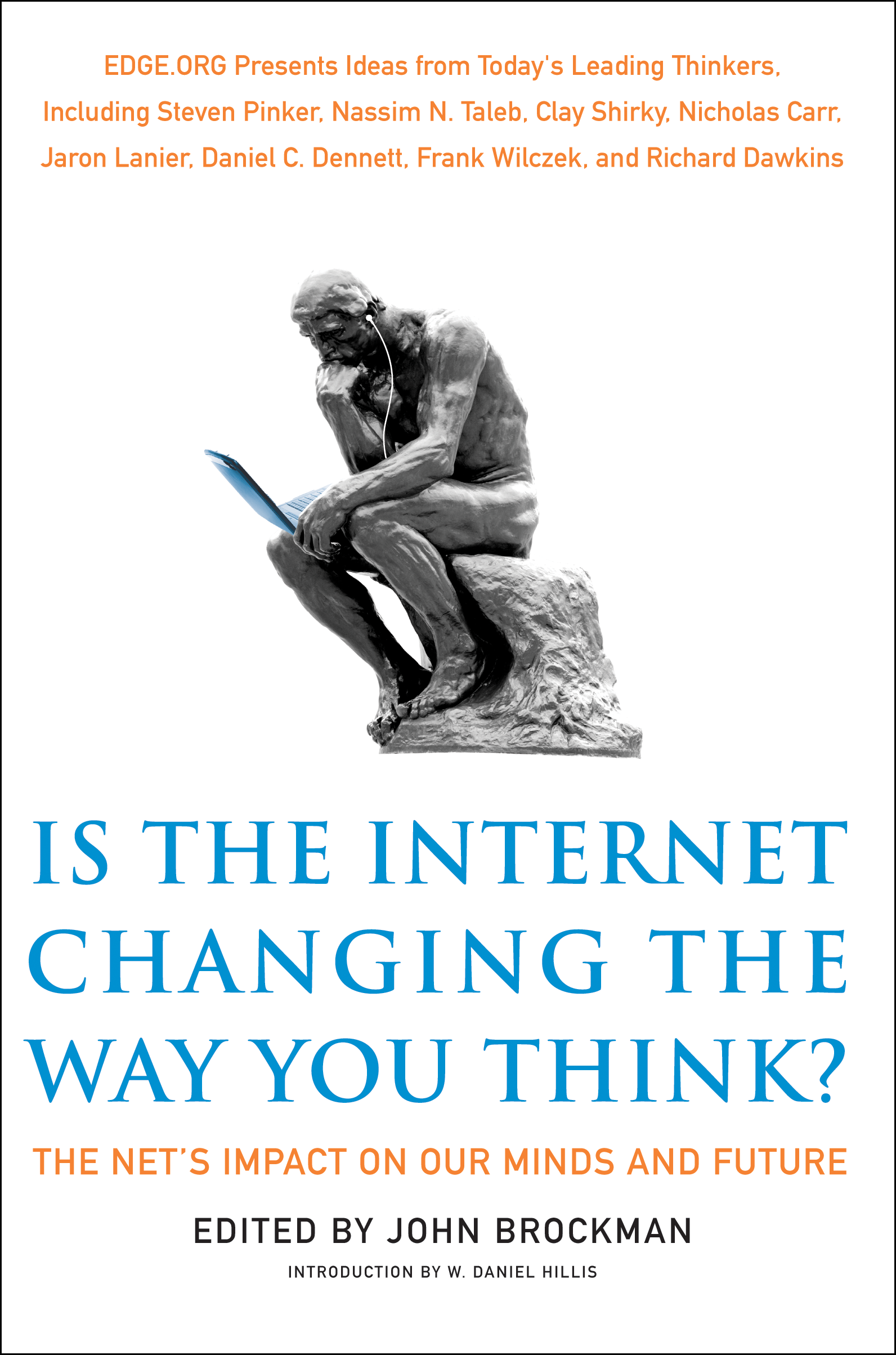

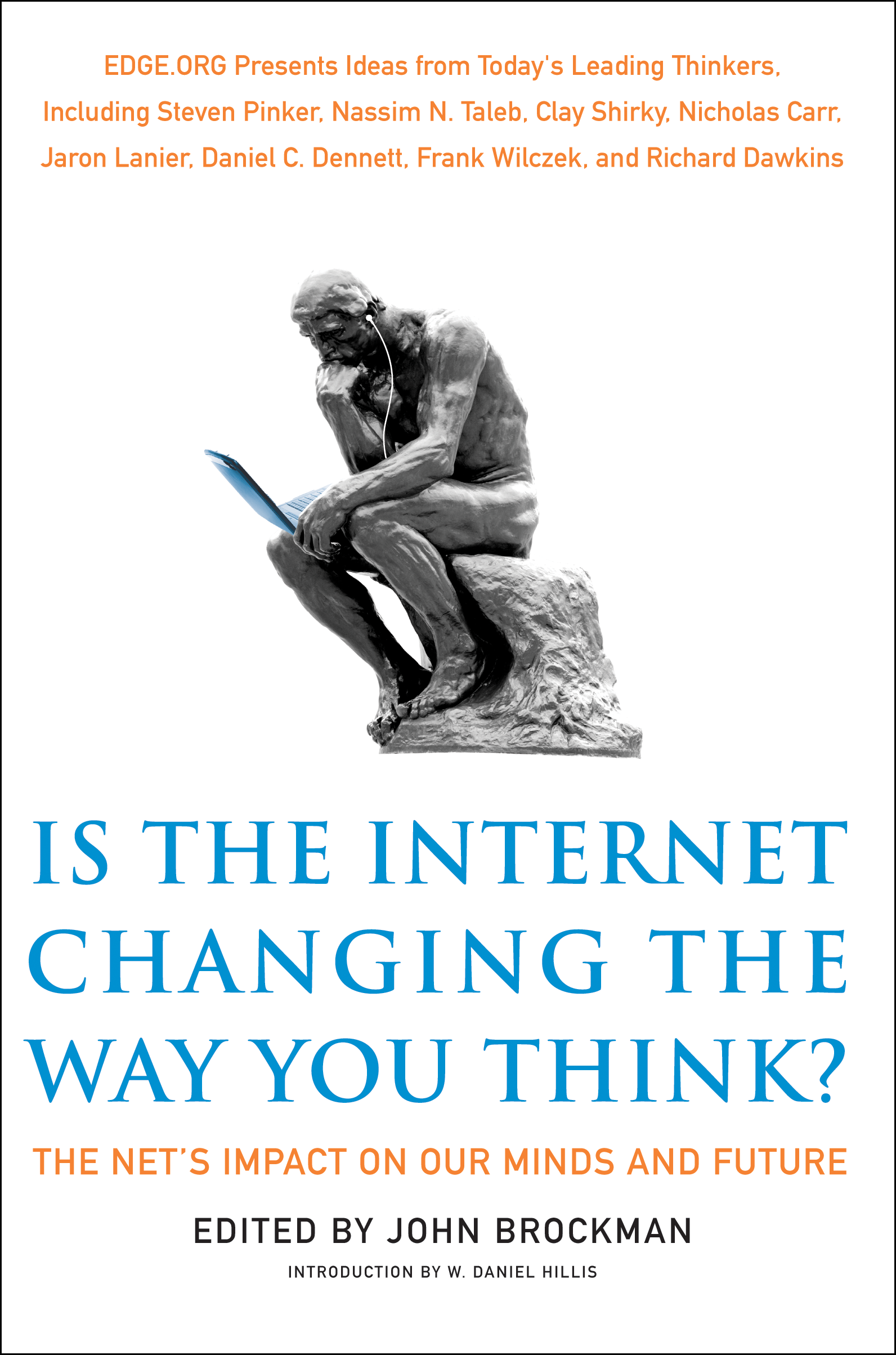

IS THE INTERNET CHANGING

THE WAY YOU THINK?

The Nets Impact on Our Minds and Future

Edited by John Brockman

To KHM

Contents

The Edge project was inspired by a 1971 failed art experiment. This venture was titled The World Question Center and was devised by the late James Lee Byars, my friend and sometime collaborator. Byars believed that to arrive at a satisfactory plateau of knowledge it was pure folly to go to Widener Library at Harvard and read 6 million books. Instead, he planned to gather the hundred most brilliant minds in the world in a room, lock them in, and have them ask one another the questions they were asking themselves. The expected result (in theory) was to be a synthesis of all thought. But it didnt work out that way. Byars identified his hundred most brilliant minds and called each of them. The result: Seventy people hung up on him.

A decade later, I picked up on the idea and founded the Reality Club, which in 1997 went online, rebranded as Edge . The ideas presented on Edge are speculative; they represent the frontiers in such areas as evolutionary biology, genetics, computer science, neurophysiology, psychology, and physics. Emerging out of these contributions is a new natural philosophy, new ways of understanding physical systems, new ways of thinking that call into question many of our basic assumptions.

For each of the anniversary editions of Edge, I have used the interrogative myself and asked contributors for their responses to a question that comes to me, or to one of my correspondents, in the middle of the night.

Its not easy coming up with a question. As Byars used to say: I can answer the question, but am I bright enough to ask it? Im looking for questions that inspire answers we cant possibly predict. My goal is to provoke people into thinking thoughts they normally might not have.

The 2010 Edge Question

This years question is How is the Internet changing the way you think? (Not How is the Internet changing the way we think? Edge is a conversation, and we responses tend to come across like expert papers, public pronouncements, or talks delivered from a stage.)

The art of a good question is to find a balance between the abstract and the personal, to ask a question that has many answersor at least a question to which you dont know the answer. A good question encourages answers that are grounded in experience but bigger than any experience alone. I wanted Edge s contributors to think about the Internet, which includes but is a much bigger subject than the Web or an application on the Internet (or searching, browsing, and so forth, which are apps on the Web). Back in 1996, computer scientist and visionary Danny Hillis pointed out: A lot of people think the Web is the Internet, and theyre missing something. The Web is the old media incorporated into the new medium. He enlarges on that thought in the introduction.

This year, I enlisted the aid of Hans Ulrich Obrist, curator of the Serpentine Gallery in London, and the artist April Gornik, one of the early members of the Reality Club, to help broaden the Edge conversationor, rather, to bring it back to where it was in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when April gave a talk at a Reality Club meeting and discussed the influence of chaos theory on her work, and Benoit Mandelbrot showed up to discuss fractal theory. Every artist in New York City wanted to be there. What then happened was very interesting. When the Reality Club went online as Edge, the scientists were all on e-mailand the artists werent. Thus did Edge, surprisingly, become a science site, whereas my own background (beginning in 1965, when Jonas Mekas hired me to manage the Film-Makers Cinematheque) was in the visual and performance arts. Gornik and Obrist have brought a number of artists into our annual colloquy.

Their responses were varied and interesting: Gorniks (with Eric Fischl) Replacing Experience with Facsimile; Marina Abramovi, My Perception of Time; Stefano Boeri, internet is wind; Terence Koh, a completely new form of sense; Matthew Ritchie, Whats Missing Here?; Brian Eno, What I Notice; James Croak, Art Making Going Rural; Raqs Media Collective, No One Is Immune to the Storms That Shake the World; Jonas Mekas, I Am Not Exactly a Thinking PersonI Am a Poet; and Ai Weiwei, who wrote, When Im on the Net, I Start to Think.

A new invention has emerged, a code for the collective consciousness that requires a new way of thinking. The collective externalized mind is the mind we all share. The Internet is the infinite oscillation of our collective consciouness interacting with itself. Its not about computers. Its not about what it means to be humanin fact, it challenges, renders trite, our cherished assumptions on that score. Its about thinking. Here, more than 150 Edge contributorsscientists, artists, creative thinkersexplore what it means to think in the new age of the Internet.

John Brockman

Publisher and Editor, Edge

W. Daniel Hillis

Physicist, computer scientist; chairman, Applied Minds, Inc.; author, The Pattern on the Stone

It seems that most people, even intelligent and well-informed people, are confused about the difference between the Internet and the Web. No one has evidenced this misunderstanding more clearly than Tom Wolfe in a turn-of-the millennium essay titled Hooking Up:

I hate to be the one who brings this news to the tribe, to the magic Digikingdom, but the simple truth is that the Web, the Internet, does one thing. It speeds up the retrieval and dissemination of information, partially eliminating such chores as going outdoors to the mailbox or the adult bookstore, or having to pick up the phone to get hold of your stock broker or some buddies to shoot the breeze with. That one thing the Internet does and only that. The rest is Digibabble.

This confusion between the network and the services that it first enabled is a natural mistake. Most early customers of electricity believed they were buying electric lighting. That first application was so compelling that it blinded them to the bigger picture of what was possible. A few dreamers speculated that electricity would change the world, but one can imagine a nineteenth-century curmudgeon attempting to dampen their enthusiasm: Electricity is a convenient means to light a room. That one thing the electricity does and only that. The rest is Electrobabble.

The Web is a wonderful resource for speeding up the retrieval and dissemination of information, and that, despite Wolfes trivialization, is no small change. Yet the Internet is much more than just the Web. I would like to discuss some of the less apparent ways in which it will change us. By the Internet, I mean the global network of interconnected computers that enables, among other things, the Web. I would like to focus on applications that go beyond human-to-human communication. In the long run, these are the applications of the Internet that will have the greatest impact on who we are and how we think.

Today, most people recognize that they are using the Internet only when they are interacting with a computer screen. They are less likely to appreciate that they are using the Internet while talking on the telephone, watching television, or flying on an airplane. Some air travelers may have recently gotten a glimpse of the truth, for example, upon learning that their flights were grounded due to a router failure in Salt Lake City, but for most of them this was just another inscrutable annoyance. Most people long ago gave up trying to understand how technical systems work. This is a part of how the Internet is changing the way we think.