My thanks to Peter Hubbard of HarperCollins and my agent, Max Brockman, for their continued encouragement. A special thanks, once again, to Sara Lippincott for her thoughtful attention to the manuscript.

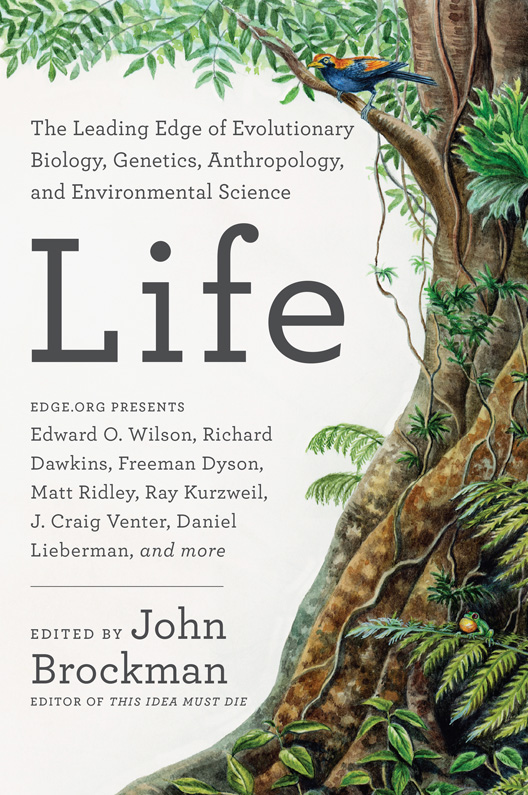

Life is the fifth volume in The Best of Edge series, following Mind, Culture, Thinking, and The Universe. Here we present eighteen pieces from the pages of Edge.org, an online salon consisting of interviews, commissioned essays, and transcribed talks, many of them accompanied with streaming video and available, gratis, to the general public.

Edge, at its core, consists of the scientists, artists, philosophers, technologists, and entrepreneurs at the center of todays intellectual, scientific, and technological landscape. Through its lectures, master classes, and annual dinners in California, London, Paris, and New York, Edge assembles the thinkers who are exploring and rewriting our global culture.

Edge.org was launched in 1996 as the online version of the Reality Club, an informal gathering that met from 1981 to 1996 in Chinese restaurants, artists lofts, the boardrooms of Rockefeller University and the New York Academy of Sciences, investment banking firms, ballrooms, museums, living rooms, and elsewhere. Though the venue is now in cyberspace, the spirit of the Reality Club lives on, in lively back-and-forth conversations on hot-button ideas. In the words of novelist Ian McEwan, a sometime contributor, Edge.org is openminded, free ranging, intellectually playful... an unadorned pleasure in curiosity, a collective expression of wonder at the living and inanimate world... an ongoing and thrilling colloquium.

This is science set out in the largely informal style of a conversation among peersnontechnical and colloquial, in the true spirit of the third culture, which I have described as consisting of those scientists and other thinkers in the empirical world who, through their work and expository writing, are taking the place of the traditional intellectual in rendering visible the deeper meanings of our lives.

Like the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis that revolutionized biology in the mid-twentieth century by marrying Mendelian genetics to Darwinian natural selection, the rise of biotechnologyepitomized by the Human Genome Project, which began in the twentieth centurys last decade and was completed in 2003constitutes a turning point in our perception of who we are and where were headed. The achievements of the past two decades have apparently made it possible for useven incumbent upon usnot just to ameliorate the ills besetting our planet but to begin participating in our own evolution.

We have assembled contributions from some of Edges best minds, among them geneticists, theoretical biologists, theoretical physicists, and bioengineers. Pioneers in the current revolution, they take us over the work leading up to and in the wake of the Human Genome Project, illuminating in the process the conversations and controversies that animate modern biology.

We lead off with a 2015 talk by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, who defends his selfish gene view of Darwinian natural selection and speculates that life elsewhere in the universe will exhibit it. Evolutionary geneticist and theorist David Haig follows, with a talk on conflicts and conflict resolution within the genome, stemming from maternal and paternal imprinting. Robert Trivers, canny lone wolf of evolutionary biology, discusses self-deception and the biased information flow between the conscious and the unconscious. The late Ernst Mayr, an architect of the twentieth centurys modern synthesis, talks to Edge about the course of evolutionary biology since then and his agreements and disagreements with it. The highly regarded geneticist and snail biologist Steve Jones comments on the robustness of Darwins 150-year-old worldview.

E. O. Wilson recalls the the divide (lately bridged) at Harvard between the morphologist/naturalists and the newly arrived molecular biologistsparticularly personified by the rambunctious Jim Watson. Theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson speculates about the future of lifewill it be analog or digital? Then, at an Edge gathering at Eastover Farm in Connecticut a few years later, he joins biotechnologist and entrepreneur J. Craig Venter, geneticist George Church, astrophysicist Dimitar Sasselov, and quantum engineer Seth Lloyd in a free-ranging discussion of the origins of life and its prospects, here on Earth and elsewhere. This is the books longest section and its centerpiece; in it, Lifes major themes and arguments play out, sometimes brilliantly, sometimes with a lot of tongue in cheek. A year later, Dawkins and Venter renew the discussion in a dialogue on their pet theories, enlivened by the issues that divide them.

Armand Marie Leroi, a developmental biologist at Imperial College London, ponders the wide range of genetic variation in the human species, along with the reluctance of some scientists to study such matters as skin color because of the long and sorry history of genetics and racial differences. The physiological legacy of our hominid ancestors is discussed by paleoanthropologist Daniel Lieberman, and our possible Neanderthal heritage by Svante Pbo, mapper of the Neanderthal genome. Craig Venter is joined by inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil and roboticist Rodney Brooks in a session on recent advances in genomics and biotechnology; bioengineer Drew Endy makes a case for focusing on the engineering aspects of synthetic biology.

Kary Mullis, inventor of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the 1980s, which enabled the sequencing and cloning of DNA, talks about his current attempts to improve the human immune system. Yale evolutionary ornithologist Richard Prum talks about the importance of aesthetics in natural selection, reviving the old argument between Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, the codiscoverer of evolution by natural selection. Along the way, he tells you more than you might want to know about the love life of ducks. Neuroendocrinologist Robert Sapolsky warns us about the ubiquity and ingenuity of the parasite protozoan Toxoplasma, and the theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman, an expert on complex systems, concludes the collection with an essay on how the universe got complex and on whether or not there are laws that govern biospheres across the universe.

Lifeand particularly intelligent lifehas been called an emergent phenomenon. But has it fully emerged? Now that we are a party to its emergence, what are the opportunities before us, and what are our responsibilities with regard to a continuing and partly man-made evolutionon (and perhaps someday off) this planet? Ought we to play God, as some naysayers have vigorously accused the twenty-first centurys geneticists and biotechnologists of doingor are we simply meeting our obligations and living up to our natural potential as human beings?

John Brockman

Editor and Publisher

Edge.org

[April 30, 2015]

Richard Dawkins is an evolutionary biologist and Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science, Emeritus, at Oxford.

Natural selection is about the differential survival of coded information which has the power to influence its probability of being replicated, which pretty much means genes. Whenever coded information which has the power to make copies of itselfa replicatorcomes into existence in the universe, it potentially could be the basis for some kind of Darwinian selection. And when that happens, you then have the opportunity for this extraordinary phenomenon we call life.